Where water is life, many on the Pine Ridge Reservation go thirsty

SETH TUPPER

High Country News

by SETH TUPPER | High country News

This story was originally published by the Economic Hardship Reporting Project and the Guardian and is reproduced here with permission.

Up until late last year, Ella Coleman, a diminutive, soft-spoken Oglala Sioux grandmother who lives in one of the hundreds of mobile homes on the semi-arid plains of the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation, lacked running water.

Sometimes, she received water deliveries by truck. Other times, she drove to a community spigot, where she filled buckets and hauled them in her minivan. At home, she ladled water from the buckets for cooking and bathing.

Finally, last fall, a not-for-profit, Running Strong for American Indian Youth, connected her home to the water pipeline. But this advance happened five years after the federal government had supposedly finished its $470-million share of a pipeline project that many tribal leaders, bureaucrats and politicians promised as a solution to chronic water problems on this impoverished reservation in south-west South Dakota.

Coleman’s struggle is emblematic of the mixed results from the Mni Wiconi pipeline, a name that incorporates a Lakota Sioux phrase often translated as “water is life.” The system’s 5,000 miles of underground pipes serve a 12,500-square-mile area that encompasses one-sixth of South Dakota.

Although the project can deliver up to 20 million gallons of potable water daily to an estimated 52,000 people – about one-fourth of them white, and the rest Native American – it has been beset by overspending and incompletion. The unfinished parts happen to be at the tribal ends of the pipeline and have become another example of unfulfilled promises by the federal government to Indigenous people.

Despite 25 years of construction that cost nearly a half-billion dollars, only about half of the water delivered by the Mni Wiconi system to the Pine Ridge Reservation is derived from the Missouri River. The rest comes from the reservation’s own wells, which were incorporated in the project to save money.

In reservation towns and villages, the new pipeline water is fed into old community water systems – some of which date to the 1960s, with pipes made of potentially hazardous asbestos-cement. The Mni Wiconi’s builders pledged but failed to replace those antiquated systems.

Willard Clifford, the Oglala Sioux Tribe’s water systems manager, summed up the Mni Wiconi project’s unfinished components this way: “Should’ve been done, could’ve been done, didn’t get done, ran out of funding.”

The Rosebud and Lower Brule reservations, which are also part of the service area, face similar struggles. The poverty rate on all three reservations exceeds 40%. Historically, a dearth of water and related infrastructure have contributed to persistent poverty on the reservations.

Meanwhile, the 15 predominantly white communities and scores of politically connected white ranchers who are served by the Mni Wiconi pipeline have reaped its full benefits. All the water flowing through Mni Wiconi pipes to those users is from the Missouri River, and their pipeline connections are funded by fees they pay to a not-for-profit, the West River/Lyman-Jones Rural Water System.

The annual per capita income is $26,526 in Jones county, where West River/Lyman-Jones is headquartered. In Oglala Lakota county, where the Oglala Sioux Tribe is headquartered, it is $9,334.

LONG BEFORE MNI WICONI, water woes plagued the western part of the state. “In most areas out west the water smells bad, it’s a perfect laxative and it kills the grass,” the late Marvis Hogen, a prominent local rancher, legislator and raconteur, told fellow legislators in 1976.

“If the water on my ranch was gasoline,” he said to the Rapid City Journal, the area’s largest newspaper, in 1980, “there wouldn’t be enough to fuel a flea’s motorcycle one trip around a Cheerio.”

After the federal government built four dams along the South Dakota portion of the Missouri River from 1946 to 1966, the vast reservoirs behind the dams were coveted by western South Dakotans. But progress toward an expensive Missouri River pipeline proved slow.

In 1981, the then governor, Bill Janklow, announced a deal with San Francisco-based Energy Transportation Systems Inc (ETSI) to bring Missouri River water to western South Dakota. ETSI needed the water for a slurry pipeline, to float crushed coal from Wyoming mines to power plants in the south. Janklow sold Missouri River water to the company but extracted the right to allow rural residents and communities to tap into the water pipeline.

But in 1984, ETSI had abandoned the project, blaming opposition from influential railroad companies that stood to lose coal-transportation contracts. Western South Dakotans, who had been planning for the water pipeline’s construction, were left with a surplus of enthusiasm and organizational momentum but no project.

So, they turned to Congress.

DURING THE MID-1980s, the state’s congressional delegation introduced multiple bills seeking funding for a pipeline to serve several counties that now make up the West River/Lyman-Jones service area.

At congressional field hearings, South Dakotans displayed brown-tinted water from their wells and sections of water pipes clogged with minerals. Yet the bills stalled. “We couldn’t get the money if it was just going to serve whites,” acknowledged Larry Pressler, Republican of South Dakota, a former congressman and senator.

Some Oglala Sioux tribal leaders expressed interest in the pipeline. They were natural partners, because the tribe’s Pine Ridge Reservation abuts the West River/Lyman-Jones area.

In June 1987, Representative Tim Johnson, Democrat of South Dakota, introduced a new bill that proposed a shared Missouri River pipeline for West River/Lyman-Jones and Pine Ridge.

The project, with its new Lakota name Mni Wiconi, found broader support; Congress passed the bill and President Ronald Reagan signed it in 1988.

The original cost estimate was $100 million. Congress authorized $87.5 million through 1999 to cover all the tribal costs and 65% of non-tribal costs. State and local sources agreed to cover the rest of the budget.

The decision to fully fund the tribal portion stemmed from a federal mandate to protect a reservation’s water supply, a responsibility rooted in treaties from the 1800s.

So, with the passage of the Mni Wiconi Project Act of 1988, Congress appeared to fulfill a long-overdue obligation, generating some support among tribal leaders. “You wouldn’t believe how many people are using outhouses and hauling water here,” tribal member Frank Means told the Medill News Service in 1989. “It’s like living in another country.”

Other tribal members were cynical. Phillip Under Baggage, who was an Oglala Sioux Tribal Council member, bluntly assessed the motivation of white pipeline backers whose previous legislation he described as “virtually dead in committee.”

“The only way to revive it was to involve an economically depressed area,” Under Baggage told the Rapid City Journal in 1988. “So, the tribe was included.”

After opposition surfaced, tribal leaders submitted the project to a referendum. The results: 1,017-873, against the project. Yet tribal officials ignored the vote, declaring the election to be a non-binding expression of voter opinion that did not overrule the council’s prior approval of the project.

THE ESTIMATED SEVEN-TO-NINE year construction project took more than two decades. It was bogged down by funding battles, the addition of two more reservations – the Rosebud and Lower Brule tribes – into the service area, and cost overruns and misspent funds.

One of the first hurdles was a lack of funding. Though Congress had set a cost ceiling for the project, it had not actually appropriated any funds for it.

Annual lobbying efforts by South Dakota’s congressional delegation and the project’s backers would eventually yield appropriations of up to $30 million in some years, but in 1989, the project received an initial appropriation of just $500,000.

The project’s engineers found that if they designed a Missouri River pipeline big enough to serve all the participants, the cost would blow past the authorized ceiling. So, they decided to obtain some of the project’s water from the High Plains Aquifer system, including the Ogallala Aquifer, which lies underneath parts of the Pine Ridge Reservation but does not extend into the West River/Lyman-Jones service area. The Oglala Sioux people were made to replace half of their share of Missouri River water with groundwater, essentially to benefit their white neighbors.

The project’s final engineering report, published in 1993, estimated the savings by using groundwater at roughly $40 million. The decision was made with the participation of tribal leaders who were involved in the project, but the cost-saving motive was not widely acknowledged.

The decision also violated the spirit of the 1988 Mni Wiconi authorizing law, which declared the Missouri River to be “the best available, reliable, and safe rural and municipal water supply to serve the needs of the Pine Ridge Reservation.”

DESPITE THE PITFALLS, Missouri River water started flowing to some project participants in the early 2000s, though it did not reach Pine Ridge reservation until 2008.

The three tribes and the West River/Lyman-Jones system were each responsible for their own bidding and contracting. Bids came in higher on the reservations, where some contractors were loath to work because of the remoteness, the complicated tribal politics and contracts requiring preferential hiring of Native Americans.

Congress kept the project alive, extending the sunset date on three occasions and raising its funding ceiling twice.

By the final sunset date in 2013, the federal contribution had reached about $470 million. Another $17.46 million came from the state of South Dakota and the West River/Lyman-Jones Rural Water System, for a total construction cost of nearly $490 million.

When the last sunset date arrived in 2013, several aspects of the project remained unfinished, and prospects for further congressional support were dim.

Congress had recently banned earmarking – the practice of inserting funds for local projects into broader appropriations bills – which had provided much of Mni Wiconi’s budget.

The project’s main congressional champion, Tim Johnson, had moved from the House to the Senate but was nearing retirement after a near-fatal brain hemorrhage in 2006. In 2012 and 2013, he proposed legislation seeking $14 million more for Mni Wiconi construction, plus whatever future sums proved necessary. The Congressional Budget Office estimated the bill would ultimately cost Congress $91 million.

The proposed legislation would have funded replacements of the community water systems on the reservations, as originally authorized by the original 1988 law, which stipulated that the water systems could be purchased from the tribes, tribal members, or other residents of Pine Ridge who owned them.

But the purchase of the systems was dismissed in the 1993 engineering report, which declared, “donation of these systems is expected.”

“A savings of several million dollars … can result from this tribal policy, if enacted,” the report stated.

The expectation that the tribes would hand over their community water systems without compensation collided with a refusal by the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation to incorporate the systems into the project until some other entity paid to replace them.

In 2012, the Bureau’s Grayford Payne testified against Johnson’s legislation, arguing that his agency had not funded the original installation of the community systems and therefore should not be required to replace them.

Johnson’s legislation ultimately failed, and Mni Wiconi construction funding expired.

DESPITE A LACK OF further construction appropriations, millions more federal dollars will probably be spent on unfinished aspects of Mni Wiconi.

Arden Freitag, area manager for the Bureau of Reclamation’s Dakotas Area Office, said that 53 community water systems need replacement across the three reservations served by Mni Wiconi. In 2014, the bureau estimated the cost to replace all of the systems at $42 million.

Partial funding has been obtained from the U.S. Department of Agriculture while more funding is sought; meanwhile, the Oglala Sioux Tribe still charges individual users of the community systems for water. Several tribal officials acknowledge that many impoverished water users do not pay their bills. “You can’t squeeze blood from a turnip,” said Willard Clifford, of the tribe’s water maintenance and conservation department.

Meanwhile, the community water systems are plagued by leaky pipes, faulty valving and insufficiently coated storage reservoirs, said Freitag.

Clifford said the outdated community water systems vex tribal water officials: “If there’s a leak in the middle of Pine Ridge,” he said, “you pretty much shut down half the town because most of the valves are not working … If it was all a brand-new system, you’d be able to isolate that by the block.”

Some of the community systems’ underground pipes are made of asbestos-cement – once a common material in pipe construction. Asbestos is now known as a carcinogen.

Clifford said the water delivered by Mni Wiconi and the community systems is safe, and EPA records reflect improvement in the water quality on the reservations compared with the pre-Mni Wiconi era. But Clifford said the asbestos-cement pipes could become a hazard if they are dug up and broken, which would release asbestos particles. Tribal officials plan to leave the old pipes in the ground and abandon them when new community water systems are installed.

SEVERAL OFFICIALS ON THE Pine Ridge Reservation estimate that 95% of the population is now connected to the water system. But that number is bolstered by the efforts of Running Strong for American Indian Youth, a not-for-profit.

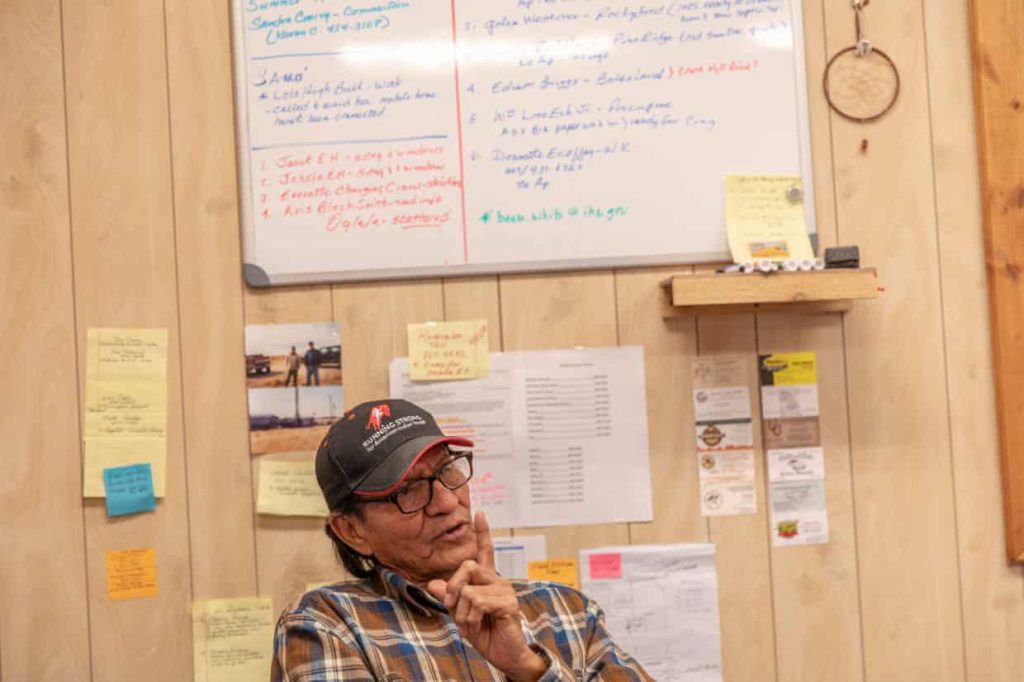

“Every spring we bring new life to families, and it’s a really good feeling when we do that,” said Ken Lone Elk, the organization’s water coordinator. Neither Lone Elk nor the Indian Health Service, a federal agency that also connects tribal households, knows exactly how many more households still need pipeline water; as of April, the not-for-profit currently has 30 families on its wait list.

Cattle producers were also supposed to benefit from the Mni Wiconi. The 1993 engineering report included a $16.67 million livestock watering network on the Pine Ridge Reservation, but it was abandoned as money ran short.

“To complete the project, we had to eliminate the livestock portion,” said Frank Means, formerly the director of the Oglala Sioux Rural Water Supply System. “We just couldn’t do that.”

Trudy Ecoffey, a tribal liaison for the Natural Resources Conservation Service, said a lack of good water in some pastures prevents the tribe or tribal members from using land for livestock grazing. “So,” Ecoffey said, “the land just sits idle, because nobody can utilize it because of the water situation.”

The incomplete aspects of the Mni Wiconi project shocked former senator Larry Pressler, who backed the project.

When asked if he thinks Native Americans were used by whites to get a water pipeline approved by Congress, Pressler said, “I would say the answer is partially yes.”

To get the pipeline through Congress, Pressler said, “It had to be renamed Mni Wiconi and had to be a Native American project.”

When people on the affected reservations field questions about the unfinished parts of Mni Wiconi, they often do so with a shrug. After all, the project is delivering treated water to thousands of Native Americans who previously lacked it, and that’s more than some skeptical Oglala Sioux voters expected when they voted against the project in 1989.

Chuck Jacobs, of the Oglala Sioux Tribe’s department of water maintenance and conservation, characterized the unfinished Mni Wiconi components as unavoidable for a project that had to fight for congressional appropriations.

“We went and asked for a Cadillac,” he said, “and I don’t want to say we had to settle for a minivan, but that’s just the game in D.C.”

Seth Tupper is an enterprise reporter at the Rapid City Journal. This article was supported by the Schumann Center for Media and Democracy and The Economic Hardship Reporting Project.