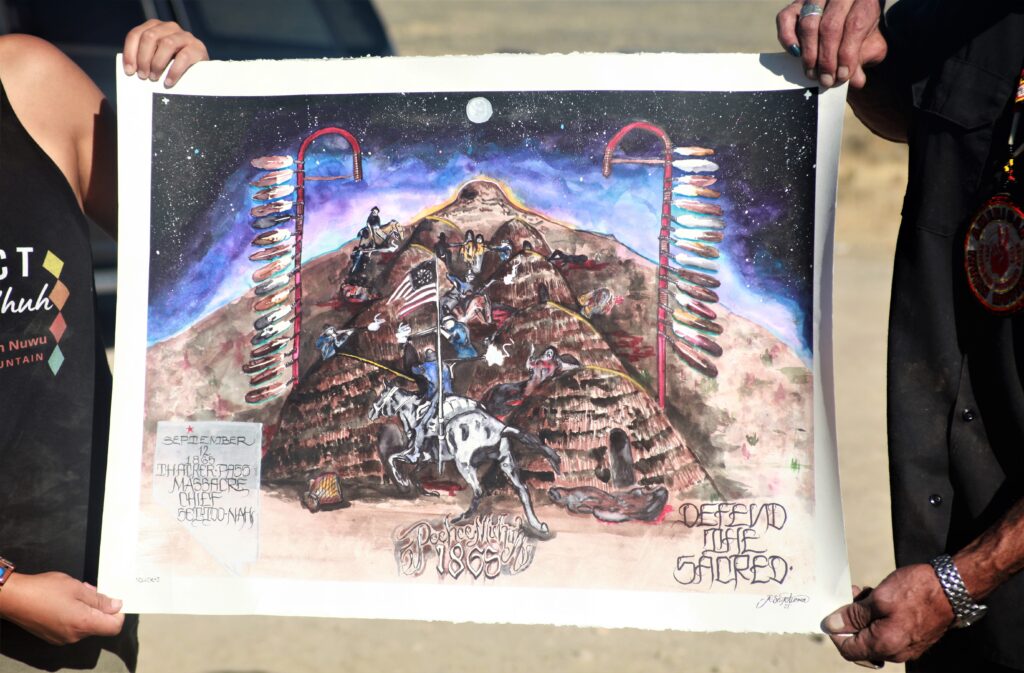

Defenders of sacred burial lands staged a die-in near the planned Thacker Pass Lithium Mine at the Peehee Mu ‘Huh massacre site in northwest Nevada. Photo by Tanya Novikova

For generations, Paiute and other Native people in this area have suffered unrequited grief over stories of relatives lost in the U.S. Cavalry’s 1865 Thacker Pass Massacre. So, when tribal leaders learned that the federal government permitted a mega-mining project in the vicinity, many said “no” to the digging.

Due to that simple word, they find themselves fending off a bid for the world’s largest open-pit lithium mine. Canada-based Lithium Americas Corp. intends to strip the site and dominate the nascent U.S. market for the prized electric automobile battery component. The endeavor responds to energy policy mandating automakers to ramp up the share of domestic raw materials in transition to a zero tailpipe emission passenger vehicle.

However, the testimony suggests that relics of 30 to 50 massacre victims potentially remain in the 18,000-acre contested permit area. Planned excavations “will likely disturb these human remains and cause irreparable harm,” the federally recognized Reno-Sparks Indian Colony says.

The colony, the Burns Paiute Tribe, and the Summit Lake Paiute Tribe filed a lawsuit on Feb. 16 to prevent the looming peril. They charged the Bureau of Land Management with failure to follow the rules on the historic preservation of Native cultural assets. The case asks the court to keep the agency from authorizing any physical disturbance.

“Oral history tells us that we Paiutes have lived in this area since before the Cascade Mountains were formed,” Burns Paiute Tribal Council Chair Diane Teeman said in a Feb. 17 media release about the lawsuit. “Our traditional ways require we live in reciprocity with all other things and never put ourselves as feeble humans above others. For this reason, our unwritten traditional tribal law requires we do everything in our power to protect it.”

Her federally recognized tribal government and that of the Reno-Sparks Indian Colony had intervened in a previous lawsuit to revoke the Thacker Pass Mine permit in 2021. The grassroots Atsa Koodakuh wyh Nuwu, or People of Red Mountain, joined them. The court rejected a Winnemucca Indian Colony attempt to intervene as untimely.

Humboldt County rancher Edward Bartell filed the initial suit. Western Watersheds Project, Great Basin Resource Watch, Basin and Range Watch, and Wildlands Defense submitted a similar complaint with the same reason as Bartell. They claimed the BLM’s permitting disregards mandatory protection of air, land, water, and wildlife. The court consolidated all those filings into one case.

In a Feb. 6 summary judgment in that case, Nevada U.S. Chief Justice Miranda Du validated the BLM’s permitting. She said the mine could move forward on all but 1,300 acres of the authorized site. She ordered the federal agency back to the drawing table only to verify company rights to its slated waste dump area.

“When the decision was made public on the previous lawsuit last week, we said we would continue to advocate for our sacred site PeeHee Mu’Huh,” Reno-Sparks Indian Colony Chair Arlan Melendez said after filing the new case. “The Thacker Pass permitting process was not done correctly. They only contacted three out of the 22 tribes who had significant ties to Thacker Pass.”

Paiute speakers call Thacker Pass Peehee Mu ’huh, or Rotten Moon, focusing the mind’s eye on images of a massacre and the location’s crescent-shaped horizon line. The name dates from a pre-contact massacre in inter-tribal conflict, according to oral tradition. The tribes applied to the Interior Department on Feb. 3 to list the whole of Thacker Pass as a “traditional cultural district,” under the National Register of Historic Places.

“Are we willing to sacrifice sacred sites, health, and internal balance for short term economic gains while giant corporations create unmeasurable wealth?”

Shelly Harjo, Fort McDermitt Paiute and Shoshone Tribes

Together the plaintiffs have worked to prevent Lithium Americas Corp.’s subsidiary Lithium Nevada Corp. from mine construction for two years. In addition to pursuing court remedies, the local opponents have conducted ceremonies, peaceful demonstrations, marches, resistance encampments, field days, signposting, and media campaigns.

When Judge Du rejected their arguments, Lithium Americas Corp. stock prices rebounded immediately. Meanwhile, calling the decision “favorable,” LAC President and CEO Jonathan Evans said it reflects “our considerable efforts to ensure Thacker Pass is developed responsibly and for the benefit of all stakeholders.”

The corporation’s position received a boost just a week earlier, on Jan. 31, when General Motors pledged to purchase $650 million worth of LAC shares. The automaker also committed to buying 100% of the lithium carbonate from Thacker Pass in the permit’s first of four estimated decades of duration. The play is the largest-ever investment by an automaker in battery raw materials and establishes GM as the biggest shareholder in Lithium Americas Corp.

Du said her ruling was not based on policy considerations. However, the Thacker Pass project is an initiative driven by climate change policy, according to both companies.

“Destroying mountains for lithium is just as bad as destroying mountains for coal. You can’t blow up a mountain and call it green.”

Max Wilbert, Protect Thacker Pass Co-Founder

Washington is wielding the national budget in favor of “zero-emission” vehicles as a response to worldwide demands to reduce petroleum-based energy consumption. The transportation sector is the largest single source of the total U.S. greenhouse gas emissions, accounting for nearly a third of the domestic contribution to the global warming crisis.

Among other incentives, the 2022 Inflation Reduction Act requires that the batteries in EVs rolling off U.S. assembly lines now contain 40% of North American extracted, processed, and recycled mineral components. The proportion gradually increases to 100% through 2029.

GM plans to take advantage of a new tax credit that covers 10% of its annual production costs for taking part in the energy transition. It counts on a sales increase from a $7,500 tax credit available to buyers of cars that meet the “made in America” battery component standards. Plus, the arrangement is set to secure Department of Energy loan funding.

Shelly Harjo, a citizen of the Fort McDermitt Paiute and Shoshone Tribes, retorted: “Are we willing to sacrifice sacred sites, health, and internal balance for short-term economic gains while giant corporations create unmeasurable wealth, deplete resources, and leave our future generations to endure the disorder the Thacker Pass mine would leave behind? I will never believe this is the best method for greener living and nor do many other Native people in our area.”

Protect Thacker Pass co-founder Max Wilbert argued that global warming is “a serious problem, and we cannot continue burning fossil fuels. But destroying mountains for lithium is just as bad as destroying mountains for coal. You can’t blow up a mountain and call it green.”

© Buffalo's Fire. All rights reserved. Content may not be reproduced without written permission from the Indigenous Media Freedom Alliance. See our content sharing guidelines for media partner usage.