The land-grant legacy

How Montana State University and extension services support Native communities today

Isabel Hicks

Bozeman Daily Chronicle VIA Montana Free Press

Sophia Moreno (Apsáalooke/Laguna Pueblo/Ojibwe-Cree) plants crops in the Indigenous gardens outside American Indian Hall on the Montana State University campus in Bozeman, Montana. (ADRIAN SANCHEZ-GONZALEZ/MONTANA STATE UNIVERSITY)

This article is part of a three-part collaborative series produced by the Bozeman Daily Chronicle, ICT and Montana Free Press, and utilizes data obtained through the national news nonprofit Grist’s “Land Grab University” investigation.

Outside American Indian Hall at Montana State University, dark soil covered in patches of snow and straw sat idle, waiting to grow new life.

It was a gray day at the tail end of winter. Clouds overhead made it easy to forget that in a few months, the garden will boast a colorful crop of sunflowers, squash, corn and beans.

These four sisters once were the basis of Indigenous food systems. Today, the ancestral garden is just a tiny corner of the Native land now home to the buildings, roads and fields of MSU.

Extending far beyond Bozeman, more than 260,000 acres make up Montana’s largest public university. Much of the acreage was allocated by the 1862 Morrill Act, whichused land taken from Indigenous peoples to form a network of “land grant” universities across the country.

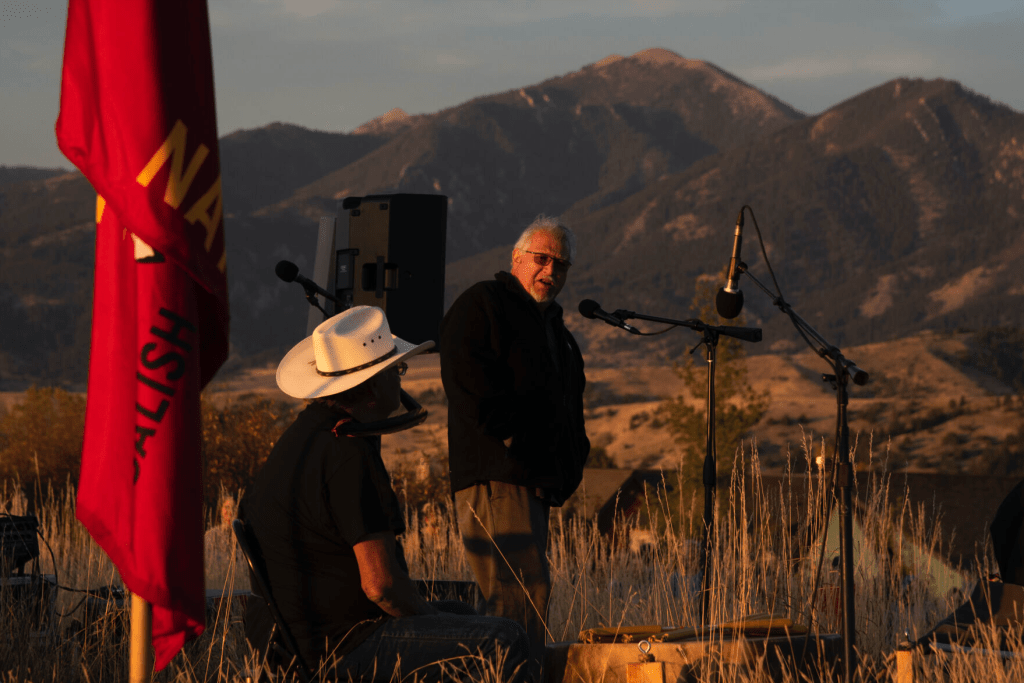

MSU Bozeman is built on ancestral lands used by the Crow, Northern Cheyenne, Salish, Kootenai, Blackfeet, Lakota and Sioux Tribes, among others.

“For centuries, colonization, invasion and dishonesty have resulted in the displacement of these people from their spiritual and cultural homelands and the lands reserved to their sovereign rule by treaty,” the Montana University System land acknowledgement reads.

Today, MSU grapples with that history — and with a responsibility to support the Native people whose land was systemically seized to form the institution.

On campus, the support involves cultural offerings, Native-specific education and tuition waivers. Off campus, tribal extension programs fuel cultural rejuvenation but sometimes struggle with funding.

University spokesperson Tracy Ellig said MSU has steadily increased its support for American Indian and Alaska Native students over the decades.

More Native people are attending MSU today than ever before, with a record 817 students — 5% of the student body — enrolled as of fall 2023. That’s a 46% increase compared to 558 students the decade before.

Walter Fleming, a member of the Kickapoo Tribe in Kansas who has chaired MSU’s Native American Studies Department for the last 21 years, said the department has grown alongside Native student enrollment.

“My characterization is that we’re not doing anything different than what we’ve always done. We’re now just doing it bigger and better,” Fleming said.

‘AT HOME’: SUPPORTING NATIVE STUDENTS ON MSU’S CAMPUS

When Fleming started teaching in 1979, only the Center for Native American Studies existed. The center achieved departmental status in 2002 after adding a minor and a master’s degree.

Today, the department has four full-time faculty, a slew of guest instructors, and its own building. Students can pursue Native American Studies as a minor, graduate degree or online certificate.

The department awarded 30 degrees in the 2023 school year and plans to add another online graduate degree in Indigenous food systems next year.

But the biggest marker of growth has been American Indian Hall, Fleming said, which opened on campus in 2021. The $20 million, 38,000-square-foot building is a flurry of sunlight and student activity.

“Students feel very much at home and feel very welcomed here,” Fleming said. “It’s the hub of activities for a number of different areas.”

The department previously held classes and office space in Wilson Hall. Fleming said they outgrew the small space years ago and started pushing for their own building.

American Indian Hall is like a second home to Maleeya Knows His Gun, a senior at MSU who grew up on the Northern Cheyenne Reservation in southeast Montana and is also an enrolled member of the Crow Tribe.

The building is a gathering space — there are always people she knows hanging out there, and lots of resources for students. It’s where all the Native events are hosted, and there’s often free food, Knows His Gun said.

Knows His Gun’s first year at MSU was 2020, and the COVID isolation made it difficult for her to meet people.

She was considering leaving MSU before American Indian Hall opened her sophomore year. That year, she was voted to be the American Indian Council’s Miss Indian MSU, and was part of the building’s opening ceremony. She continues to attend American Indian Council events, including dancing, meat-cutting workshops and jewelry-making classes.

“American Indian Council is definitely a support system for all of the Native students here on campus. Without it, I don’t think I would have stayed at MSU,” Knows His Gun said.

Knows His Gun also leads the Missing and Murdered Indigenous Peoples club at MSU. The group works to spread awareness about missing Indigenous people, and also raises money to support affected families — work that she wants to continue back home in Ashland after graduating.

Getting involved in those extracurriculars was important to Knows His Gun, who said that being away from home is hard for Native students.

“That’s why a lot of people drop out. Our communities back home are so tight-knit that when we leave and come to a place where we don’t know anyone, it definitely takes a toll on us,” Knows His Gun said. “So to me, it just means the world to know that I’m four hours away from home but still doing the work to be active in my community.”

Making sure Native students feel connected to their cultures has always been a goal of the Native American Studies Department, Fleming said. One program finds language teachers who offer in-person or remote classes for six Native heritage languages, including Salish, Cheyenne and Crow. The courses are not for credit, but instead provide an avenue for students to stay connected to their homes.

Of course, Native student retention is not just the duty of the Native American Studies Department, but is necessary university-wide, Fleming said.

MSU’s Ellig agreed, and emphasized the university’s growing financial support for Native students. In addition to outside scholarships, the Montana American Indian Waiver and the Tribal Homeland Scholarship Waiver can help cover MSU tuition for Native students.

In 2024, MSU provided $2.1 million in those tuition waivers, with 290 Native students receiving an award that averaged $7,250 per student, Ellig said. That’s a 76% increase from the $1.19 million awarded a decade ago, in 2014.

MSU also has several specific programs to support Native student education, Ellig said. For example, the College of Nursing’s Caring for Our Own Program provides nursing students summer opportunities to work in tribal nations.

SHARING KNOWLEDGE AND CULTURE: ‘REWARDING’ WORK OF TRIBAL EXTENSION PROGRAMS

But the most consistent way land-grant universities serve their surrounding communities is through extension services.

MSU Extension faculty and specialists serve the entire state, including tribal communities, conducting research and offering youth development programs such as 4-H and skill-based workshops.

Over a century after the Morrill Act established land-grant universities, in 1994, all seven Montana tribal colleges received land-grant status — allowing them to establish their own extension offices.

But today, some tribal positions are empty, and programs have shuttered from a lack of funding.

While county extension programs are routinely funded by taxes and the MSU Extension budgets, tribal extension offices must compete for limited grant funding through the Federally Recognized Tribal Extension Program.

Over time, competition for the same pot of money has grown. Tribal offices must apply for competitive grants every four years.

A handful of Indigenous students and recent college graduates interviewed by ICT expressed frustration with the general lack of knowledge among peers and course curriculum about tribal lands upon which public institutions sit and prosper.

by Renata Birkenbuel, ICT03.08.2024

Northern Cheyenne Extension, which used to do extensive programming about drought management for ranchers, among other events, lost funding a few years ago. Neither the Crow nor Rocky Boy’s reservations have their own extension offices, either.

Tribal college programs are also grant-funded through the Tribal Colleges Extension Program.

Because future funding isn’t guaranteed, there’s less job security for tribal extension agents. Unlike their county counterparts, it is logistically more difficult to apply for tenure or get a raise.

The federal government controls the funding structure, which is out of the hands of MSU. But in Montana, it means that many extension agents do the work of multiple people, covering for empty jobs in tribal colleges or extension offices.

Liz Werk has worked for extension on the Fort Belknap Reservation in north central Montana for 13 years. She’s held an array of positions and currently serves as the community vitality agent.

Two other women run the Fort Belknap extension office with Werk, and historically they have collaborated with Aaniiih Nakoda tribal college. Right now, the college and reservation agriculture extension agent positions are open.

Werk and her co-workers have been trying to fill the gaps, as gardening has become a hugely popular program. Partnerships help, including the work of MSU’s Buffalo Nations Food Systems Initiative to distribute seed bundles to gardens across Fort Belknap.

In general, Werk said, Fort Belknap Extension’s relationship with MSU has improved over the years, and MSU President Waded Cruzado has been attuned to the needs of Native communities.

During the last funding cycle, MSU Extension started helping tribal extension offices with the grant process, which has been a welcome support, Werk said.

“I am happy with the progression. It’s slow, but it’s happening,” Werk said. “I think that MSU is supportive, especially this administration, and we’ve had a good relationship with them. They’ve allowed us to do what works for our community, and we appreciate that.”

Terrance Gourneau, director of the Agriculture/Extension Program at Fort Peck Community College, said extension funding is of huge value for the reservation in northeast Montana.

The reservation extension agent job is currently empty, so the tribal college extension program is shouldering reservation-wide programming, like holding powwows and petting zoos in five different towns last summer.

“We decided that it was better to take our show on the road and go into the smaller communities,” Gourneau said. “It’s been rewarding.”

In recent years, horsemanship workshops have been a highlight for children at Fort Peck.

Many smaller children who attend the workshops are afraid of the horses at first. But they quickly gain confidence and learn how to ride — that’s a magical day for them, Gourneau said.

Some of the workshops include healing trail rides, which start with a prayer to honor the horses and the land. Some older children come to each workshop and help the younger ones.

The goal of the programming is for people to reconnect with cultural activities and learn their significance, said Jonnie Huerta, the extension office’s cultural event coordinator.

Events she leads include teaching people about medicinal plants and their uses. She’s also taught crafting classes, ranging from warbonnet making to brewing tea with tree bark to foraging and drying berries.

Huerta said she’s led at least one event per week since she started in the role last May.

“This is communal knowledge,” Huerta said. “If you live on the reservation, it’s not just Native people that need to learn our culture. I feel like it should be everybody. That’s how we’re going to gain the respect we deserve.”

People have also started to reconnect with gardening. The extension office recently started funding a community garden and greenhouse on campus, and events distributing seeds and plant starts have encouraged people to start gardens in their own backyards.

Karen Fleener, now the garden program manager, said the campus greenhouse sat empty for years. There was so little interest in gardening that it was used for storage.

But two years ago, a grant allowed a professor to use the greenhouse for vegetable production. Fleener was enlisted to help, and eventually the work evolved to her managing the community garden, which she runs with the help of one student intern, Resa Longtree.

Now, Fleener and Longtree give produce from the community garden to programs supporting veterans and the elderly at Fort Peck. Vegetables are also used at the college, like at a workshop on making salsa verde where students use tomatillos from the garden.

The garden has everything you could ask for except good soil, Fleener said. Not long ago, the garden space was a parking lot. So, much of the focus has been on improving soil health each year through methods like composting, mulching and eliminating tillage.

In an effort to maintain organic matter, the gardeners snip off the tops of weeds but leave their roots in the soil, Fleener said. It’s the little things — like the ecological difference between a till and a no-till system — that she tries to teach students.

Gourneau said the sharing of knowledge, led by extension, allows these lessons to be preserved and passed down through generations.

“We’re resurrecting things that have been lost to the wayside,” he said. “I think that’s our job as extension. And we are doing it.”

Related: Land, wealth and higher education