Tempers flare over definition of tribes, Alaska Native Corporations

Joaqlin Estus

Indian Country Today

Pictured here, the Anchorage office of Arctic Slope Regional Corporation. Photo by Joaqlin Estus / Indian Country Today.

ANCHORAGE, Alaska – The issue already went to the Supreme Court but supporters of two sides of the debate argued again last week over the definition of tribes vs. Alaska Native corporations.

At the mid-year conference of the National Congress of American Indians, the Yup’ik village of Akiak submitted a resolution calling for the organization to closely monitor federal legislation benefiting tribes. The goal was to make sure Congress doesn’t inadvertently direct money meant for federally recognized tribes to other entities.

Discussions were heated June 14 at a Jurisdiction & Tribal Government subcommittee meeting at the conference and again at an Alaska caucus meeting June 15. By June 16, after shelving the controversial resolution, Alaska delegates were calling for unity.

At issue is the definition of tribes. Alaska is unique in that the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act of 1971 created and transferred title to 40 million acres and almost $1 billion dollars to for-profit Native corporations, not to federally recognized tribes.

The companies were created to develop their lands to make a profit and issue dividends to shareholders.

Shareholders were enrolled tribal citizens alive on Dec. 18, 1971, the day the bill was signed into law by President Richard Nixon, and people who inherited shares. Some of the corporations have since opened their rolls to issue shares to descendants of shareholders. A small fraction of shares are owned by non-Natives who inherited them.

Congress also tasked the corporations with providing scholarships to shareholders, language and cultural preservation, and shareholder employment. The corporations have been empowered by Congress to hold consultations with federal agencies as do tribes. They also are eligible for special advantages in federal contracting afforded to tribes.

Congress in 2020 directed that $8 billion under the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act, or CARES, go to “tribal governments.”

The act then referenced the Indian Self Determination and Education Assistance act, which defines tribes as those tribes, nations, and Alaska Native corporations “recognized as eligible for the special programs and services provided the United States to Indians because of their status as Indians.”

In court, the Treasury Department and Native corporations said this language clearly included the corporations.

Challengers, which included both Alaska and Lower 48 tribes, said Alaska Native villages possess governmental powers like states and local governments entitled to CARES relief funds, while Native companies do not, and thus the corporations should be excluded from CARES.

The case was appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court (Yellen vs. Confederated Tribes of the Chehalis reservation), which in 2021 ruled in favor of the corporations, making them eligible for about $500 million of the $8 billion allocated to tribes.

Some took the resolution last week to closely monitor Congressional language on tribes as an intended blow against Alaska Native corporations.

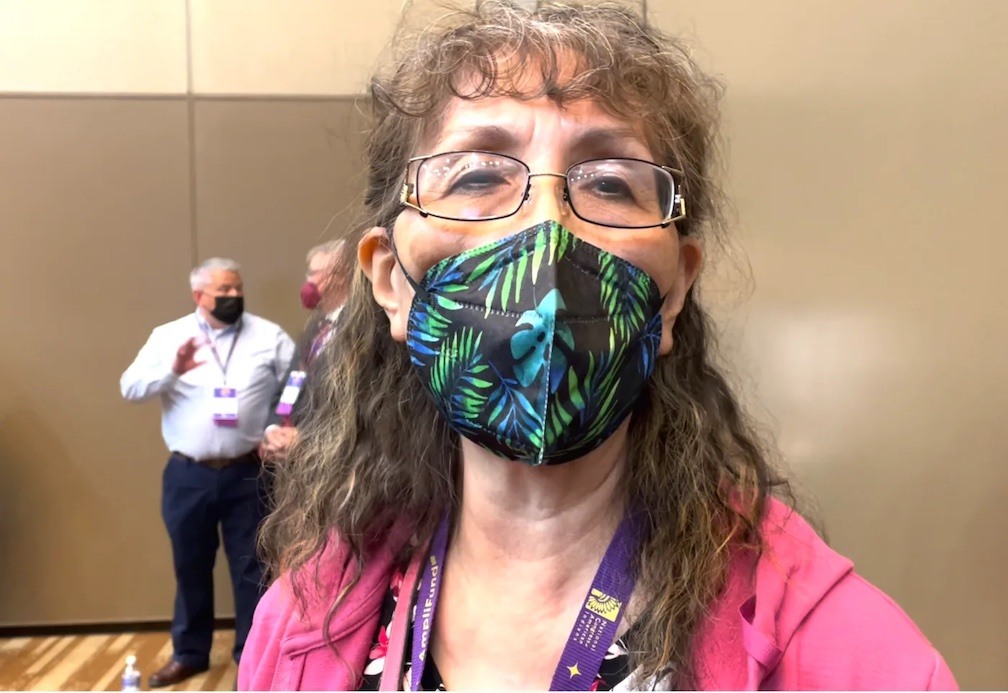

Virginia Commack, Inupiaq, of Ambler, doesn’t see it that way. She supported the resolution, saying it would make clear Congressional intent and render contentious lawsuits unnecessary.

“Legislation needs more scrutiny because I experience ANCSA (Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act) law and the legislation in Congress should be scrutinized. And tribal people should talk to each other and stand united because we are the people that were mistreated in America,” she said.

She called the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act an “experimental law.” And, she said, “ever since that came, Alaska has become divided. It’s a divisive law itself. We would have no problem if we had the same thing like in the lower 48 where we are just tribal governments.

“Our people are good people. We get along and our culture is to help each other. And when something divisive like this approaches us, it makes our people suffer,” Commack said.

She said the corporations are a means of assimilating Alaska Natives into western culture. “We need to be careful on how we make decisions, because we have been affected. Generational curse is real. Those that have become knowledgeable of the Western ways seem to be on a different road and leaving us behind, the real people, the culture, the cultural people,” Commack said.

She said in her village, the regional Native corporation didn’t send money to the tribe to administer. NANA sent shareholders and elders direct payments but she said, “the city government got mostly some CARES act money from the borough government and also from NANA (Alaska Native regional corporation). Actually, it was more divisive for us in the long run.”

During two of the three meetings on the topic, most people disagreed with Chief Mike Williams, whose village sponsored the resolution. A few said, “I’ve stood with you on other issues but on this, you’re wrong.” Others spoke loudly, saying, “you’re disrespectful, “you’re dividing our community,” and “you just want to keep it (funding) all for yourself.”

“You’re letting Lower 48 tribes (inappropriately) dictate policy for Alaska,” said one of several people who criticized the makers of the resolution for bringing it up in a national forum instead of handling it locally or statewide first. “This should have been brought up in tribal resolutions.” “You need to talk with all of us first before presenting something like this at NCAI (the National Congress of American Indians).”

At times, discussion moderators Akiak Chief Mike Williams, Yup’ik, and Native American Rights Funds attorney John Echohawk, Pawnee, were hard pressed to share their thoughts as they were interrupted by people calling out, “point of order,” questioning whether they were following correct procedures under Robert’s Rules of Order when describing the resolution.

Commack said, “I would like to say to all Native people in the United States, we need to visit how we were treated and never treat each other that way, disrespectfully. We have to calmly speak to each other instead of tearing down our tribal people. No matter how much we don’t agree with someone, we should not be screaming, hollering, because that’s not our culture. We’re supposed to sit down, go to the person who has an issue against me, go to them and try to solve it.”

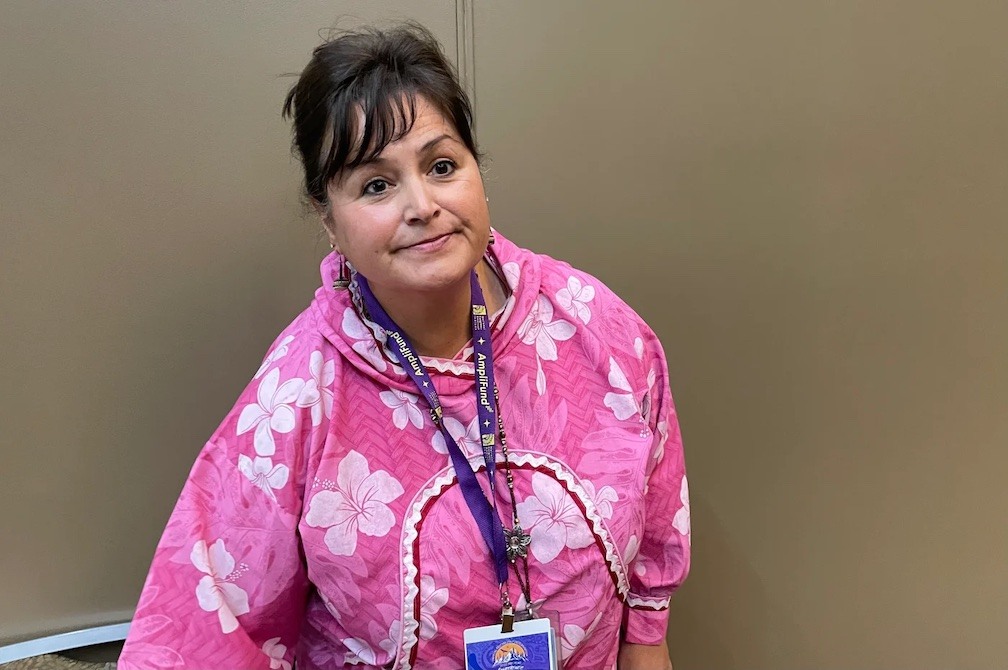

Sheri Buretta, Alutiiq, board president for the Native regional corporation Chugach Alaska, agreed it’s important to keep discussions civil and calm, despite differences.

“It’s been very hurtful, the whole Chahalis lawsuit that was filed. You know, when we were dealing with a global pandemic trying to protect our communities, we had to stop, and start fighting our own people, our brothers and sisters in the lower 48. And it was so hurtful. And the outcome was that we won that case. So this should not be coming up again at the national level.”

“My hope is that this conference being here will allow for education and understanding that we (Alaska Native corporations) are different,” she told ICT. “We were structured different, but that doesn’t mean that we’re wrong. That doesn’t mean that we’re bad, or because we have corporations that we’re not tribal people,” she said.

“I hope that there’s an opportunity to learn and to heal and to stand together and fight for our people and, and not allow for divisiveness to continue amongst our communities, that we stand together with the Indigenous people of these lands, for the lower 48 states and Hawaii, the Native people of Hawaii, and to help our people to be stronger and healthy,” Buretta said.

Beretta said last year’s lawsuit took time that the corporations could have better used to make and carry out plans for distributing the funds to do the most good. Because the issue was in litigation but the deadline for spending the money loomed, Alaska Native corporations had to move quickly to distribute the funds.

She said Chugach made direct payments to shareholders and small businesses that applied and were eligible to receive funds. “We gave funding to our tribal councils and our communities … and to homeless (programs). Through the Alaska Federation of Natives, we funded the navigator program (which helps tribes and corporations navigate federal funding programs) and the artist relief program,” Beretta said.

“We did good work with it. We did, and it was much needed. That money needed to come into our community and help our people. We should not have been denied. We should not have been questioned about our intent,” she said.

If the money hadn’t come to the Alaska Native corporations, she said, “it’s not like the tribes would get more up here. It’s just that Alaska would get less.”

The resolution was tabled indefinitely. The Alaska caucus met again on June 16, when tribal and corporate leaders from Kodiak, in south central coastal Alaska, described ways they stay united despite disagreements.

Joaqlin Estus, Tlingit, is a national correspondent for Indian Country Today. Based in Anchorage, Alaska, she is a longtime journalist. Follow her on Twitter @estus_m or email her at jestus@ictnews.org.