Sacheen Littlefeather has no regrets

Dianna Hunt

ICT

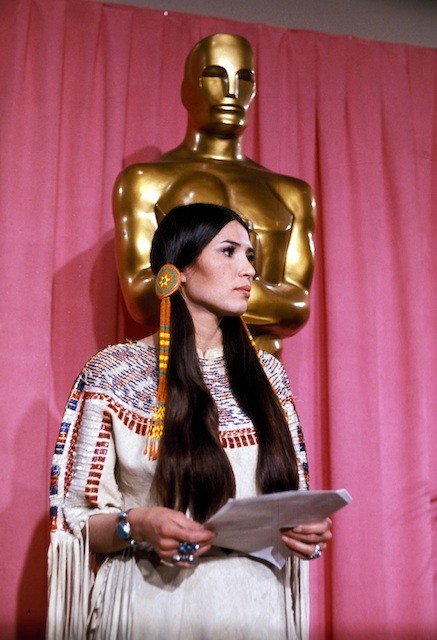

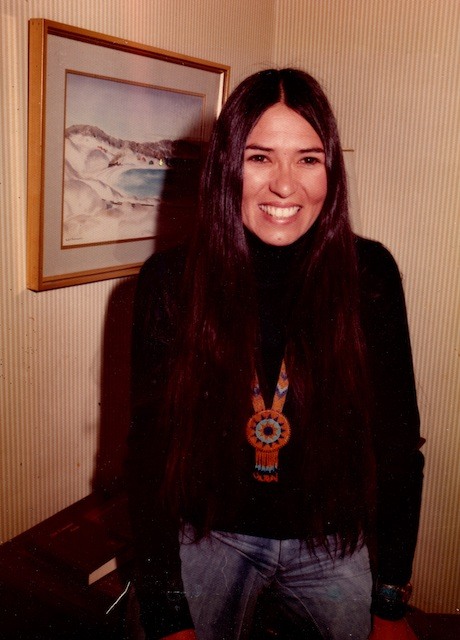

Sacheen Littlefeather, now 75, received an apology from the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences in June 2022 for the harsh treatment she received after stunning the Academy Awards in 1973 with a speech rejecting the Oscar for best actor on behalf of Marlon Brando. (Photo courtesy of Sacheen Littlefeather)

It was a quiet protest, delivered as Sacheen Littlefeather lived her life — with dignity, grace, compassion and honesty, the way her ancestors would have wanted.

But the calm words delivered to the Academy Awards on March 27, 1973, on behalf of actor Marlon Brando focused the world’s attention on the plight of Indigenous people in a way that had never been done before.

As the first Indigenous woman ever to stand at the podium at the Academy Awards, she put a spotlight on the inhumanity, stereotypes, disrespect and derision that Indigenous people faced in film and television, and brought the Wounded Knee protest to an international audience.

“I did not go up there in protest, with an up-in-the-air fist, with profanity, with a loud, screeching voice,” Littlefeather, now 75, Apache and Yaqui, told ICT in a recent interview. “The way that I went up on stage was prompted by my ancestors. I prayed that my words would meet not with deaf ears but with open hearts and open minds.”

Instead, her speech drew boos, insults, slurs, war whoops, tomahawk chops and threats of arrest, and actor John Wayne reportedly tried to charge the stage to remove her. In the days and weeks that followed, she was ostracized professionally as well, putting a damper on her acting career.

It didn’t stop her – she went on to become a traditional nutritionist, working to help people and educate the health industry about Indigenous medicine. She co-founded the American Indian AIDS Institute in San Francisco, worked with Mother Teresa, and pushed for the canonization of Kateri Tekakwitha, the first Native woman to become a Catholic saint.

Then, in June, nearly 50 years after the landmark speech, came a final response she had not expected – a formal apology from the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, billed as a “letter of reconciliation.”

“As you stood on the Oscars stage in 1973,” wrote then-Academy President David Rubin, “you made a powerful statement that continues to remind us of the necessity of respect and the importance of human dignity.

“The abuse you endured because of this statement was unwarranted and unjustified. The emotional burden you have lived through and the cost to your own career in our industry are irreparable. For too long the courage you showed has been unacknowledged. For this, we offer both our deepest apologies and our sincere admiration.”

Littlefeather is set to appear in “An Evening with Sacheen Littlefeather” on Saturday, Sept. 17, at the Academy Museum of Motion Pictures, with Bird Runningwater, Cheyenne and Mescalero Apache, who now heads the Academy’s Indigenous Alliance. The event – billed as a conversation of “reflection, healing and celebration” – was free but no seats remain available.

It marks a new era for the Academy, Ruben said.

“Today, nearly 50 years later, and with the guidance of the Academy’s Indigenous Alliance, we are firm in our commitment to ensuring Indigenous voices — the original storytellers — are visible, respected contributors to the global film community,” he wrote.

“We are dedicated to fostering a more inclusive, respectful industry that leverages a balance of art and activism to be a driving force for progress,” he said. “We hope you receive this letter in the spirit of reconciliation and as recognition of your essential role in our journey as an organization. You are forever respectfully ingrained in our history.”

Littlefeather was shocked.

“I never expected anything like this,” she told ICT. “And I’m glad that I am still alive to receive it.”

Fast friends with Marlon Brando

Brando was the favorite to win the Oscar in 1973 for best actor for his performance in “The Godfather,” which drew a slew of nominations, including for Best Picture.

By then, Brando had been outspoken in his support of Indigenous people and the injustices they faced. The occupation of Alcatraz had drawn attention to the American Indian Movement, and a protest at Wounded Knee had just begun.

And he had no intention of accepting an Oscar, so he arranged for his friend Littlefeather to go in his place, refusing to accept the award on his behalf in protest of the ill-treatment of Indigenous people in the film industry. He made Littlefeather promise she wouldn’t even touch the statuette, and she agreed.

Littlefeather met Brando through an odd set of coincidences. At the time, she lived in California near the home of Francis Ford Coppola, director of “The Godfather,” and often saw him sitting on his porch as she walked through the hills near San Francisco. When she heard Brando speak out about Indigenous issues, she wrote a letter to him to find out if he was sincere. With Coppola’s help, it was delivered.

She had been involved with the American Indian Movement’s occupation of Alcatraz in 1969-1971, and been active with other Indigenous organizations.

She didn’t get an immediate response to the letter, however, until months later, when she received a call one night at the San Francisco radio station where she worked as public service director.

“I bet you don’t know who this is,” the caller said, according to a documentary about her life, “Sacheen: Breaking the Silence.”

She recognized him immediately and chided him for taking so long to respond.

“You beat Indian time all to hell,” she said.

They became fast friends.

As the 45th Academy Awards approached, Brando asked her to take his place at the ceremony, and he wrote a lengthy statement that he asked her to read if he won. By then, Littlefeather was a member of the Screen Actors Guild and was president of the National Native American Affirmative Image Committee.

That night, however, the show’s executive producer saw her holding the eight-page, typed statement and threatened to have her arrested if she spoke more than 60 seconds, she said.

When Brando was announced as the winner, she stepped up to the podium wearing a beaded buckskin dress, moccasins and beaded hair ties – the clothes she wore to powwows. She refused to take the statuette from presenters Liv Ullmann and Roger Moore, and improvised a speech based on what Brando had wanted.

“I’m representing Marlon Brando this evening and he has asked me to tell you in a very long speech, which I cannot share with you presently because of time but I will be glad to share with the press afterwards, that he very regretfully cannot accept this very generous award,” she said.

“And the reasons for this being are the treatment of American Indians today by the film industry – excuse me – and on television in movie reruns, and also with recent happenings at Wounded Knee,” she said. “I beg at this time that I have not intruded upon this evening and that we will in the future, our hearts and our understandings will meet with love and generosity. Thank you on behalf of Marlon Brando.”

She was escorted off stage to meet with the media, then returned to Brando’s home.

“He told me I did well,” she said. “He was proud of me.”

The speech created an uproar, but there were cheers at Wounded Knee, where AIM leaders Oren Lyons, Russell Means and Dennis Banks were several weeks into the occupation there. They had gotten early word from Brando that something was up, she said.

The publicity brought an onslaught of media from around the world to Wounded Knee, where the standoff would continue for more than two months.

“They were so happy at Wounded Knee,” she said.

Life after the 1973 Academy Awards

Littlefeather didn’t give up on the film industry after delivering her speech at the Academy Awards at just 26 years old.

She attended classes at the American Conservatory Theater in 1974, and appeared in several films over the next few years, including an uncredited performance in “Freebie and the Bean” in 1974.

She appeared in the 1975 movie, “Winterhawk,” filmed in Montana, in the 1975 film, “Johnny Firecloud,” and in the 1978 film, “Shoot the Sun Down,” and toured with the Red Earth Theater Company.

But pressure was also placed on film studios and directors not to include her in productions – part of a documented effort in the 1970s to blacklist Native people who supported the AIM movement and other Indigenous causes.

A series of health issues, including a lung collapse at age 29, encouraged her interest in health care. She received a degree from Antioch University in holistic health and nutrition, with an emphasis on Indigenous medicine, and worked with a number of universities and health care organizations to spread the importance of incorporating Indigenous medicine into mainstream medicine.

“I’ve never carried hate inside my heart for anyone; I never had a grudge against the Academy Awards,” she said. “I was talented as a young person, and I had a lot going for myself. You accept what is.”

She helped found the American Indian AIDS Institute in San Francisco and served as secretary and board member in 1988, and also worked with the Gift of Love AIDS hospice in San Francisco, which was founded by Mother Teresa.

And she remained active in California’s Indigenous community, fighting against Indigenous mascots and holding prayer circles for the canonization for Kateri Tekakwitha, an Algonquin and Mohawk woman from the 1600s who converted to Catholicism after being severely scarred by smallpox. Tekakwitha was beatified by Pope John Paul II in 1980 and canonized by Pope Benedict XIV in 2012.

In 1989, she married Charles Koshiway, an Otoe from Oklahoma. She said they were “very much in sync,” and danced frequently at powwows. They had been married for 32 years when he died in November 2021.

In 2018, she was diagnosed with advanced breast cancer. She told The Guardian in 2021 that the cancer had metastasized to a lung and that she was terminally ill.

“I’ll have a plot next to him when it’s my time to go to the spirit world,” she told ICT.

Long-ago wishes

Today, Littlefeather lives in the San Francisco Bay area with occasional help from a niece who calls her Aunty.

She was caught off guard by a visit in June from Jacqueline Stewart, director and president of the Academy Museum of Motion Pictures, who arrived for a taping session with what she said were two presents.

The first gift was a photo of the museum exhibit of Littlefeather’s speech at the 1973 awards ceremony. The exhibit holds a place of honor at the museum, next to an exhibit of Sidney Poitier, who in 1964 became the first Black actor to receive an Academy Award as best actor.

The other gift, Stewart said, was the apology letter from the Academy.

“I never thought anything like this would ever happen in my whole lifetime,” she told ICT. “This is an apology that is being given to all Native peoples – not just to me, myself and I, but to we, us and our. My response was on behalf of all of us who suffered years and years of humiliation, of poor self-esteem because of the stereotyping of our people, having to live under the stereotypes of the film and television and sports industries.”

The apology fulfills the wishes she made long ago.

“I prayed that I would walk with dignity, and honor, the way our Indian women have done throughout the ages,” she said. “This is my tribute to all Indian women, past and present. The truth lives on throughout the test of time, and this apology represents that.”

In recent years, she has relished the changes in the industry – with Buffy Sainte-Marie winning an Oscar in 1983 for best original song for “Up Where We Belong,” for “An Officer and a Gentleman.” With Sterlin Harjo winning acclaim for the series, “Reservation Dogs,” and the success of “Rutherford Falls” and other productions.

She delights in seeing the roles of Native women and other Indigenous actors, producers and directors, and hopes she contributed to the changes.

“The doors are open now for Native people, in a way they were not when I was younger,” she said. “To see the doors open up little by little is a dream for me come true. If I did anything to help in that direction, I’m more than gratified.”

And she has no regrets about the path her life has taken.

“When I was young and gorgeous back in the day, I promised myself I would never be bored,” she said. “And I never have.”