The billboard project is expanding to Oregon

Reservation braces itself after OB-GYN program closes

Indigenous women in South Dakota often lack access to specialized maternal healthcare, leading to higher rates of poor outcomes

Amelia Schafer

Rapid City Journal + ICT

The Couteau Des Prairies Health Care System, a 25-bed, nonprofit hospital, is the only inpatient resource for the entire reservation and was the only hospital with a functioning OB-GYN Department until February 1, 2024. (Photo by Amelia Schafer, ICT/Rapid City Journal)

*This is part one of a two-part series on maternal healthcare in South Dakota

SISSETON, S.D. – On a small reservation in the northeast corner of South Dakota, a beige, one-story building here serves the healthcare needs of the Sisseton Wahpeton Oyate. The Couteau Des Prairies Health Care System, a 25-bed, nonprofit hospital, is the only inpatient resource for the entire Lake Traverse Reservation and was the only hospital with a functioning OB-GYN Department.

But as of February, the hospital no longer provides specialized women’s healthcare.

“The Coteau Des Prairies Health Care System looked at what would be best for the patients and the competency that our staff and obstetrics provider had,” said Craig Kantos, the hospital’s CEO. “We had one obstetrics provider and he was leaving. The days of having one OB provider who is on call 24/7 aren’t feasible anymore.”

The closure of the reservation’s only OB-GYN program illustrates the many challenges facing healthcare providers fighting against disproportionate rates of Indigenous infant and maternal mortality.

Over three-quarters of Coteau Des Prairies’ patients are Indigenous, Kantos said. In 2023, 45 babies, most of whom are Indigenous, were born there. Each and every baby is listed on the hospital’s website with their name, birthday and a photo.

While there is another medical facility in Sisseton, the Indian Health Service-operated Woodrow Wilson Keeble Memorial Health Care Center is only an outpatient clinic not equipped for emergency births or specialized care.

The reservation, which borders North Dakota and Minnesota, is the home of the Sisseton Wahpeton Oyate – two bands of Santee Dakota people forcibly relocated from their homelands in southern Minnesota. Situated over 90 miles from any large city, the reservation is a rural area with few opportunities for specialized medical care.

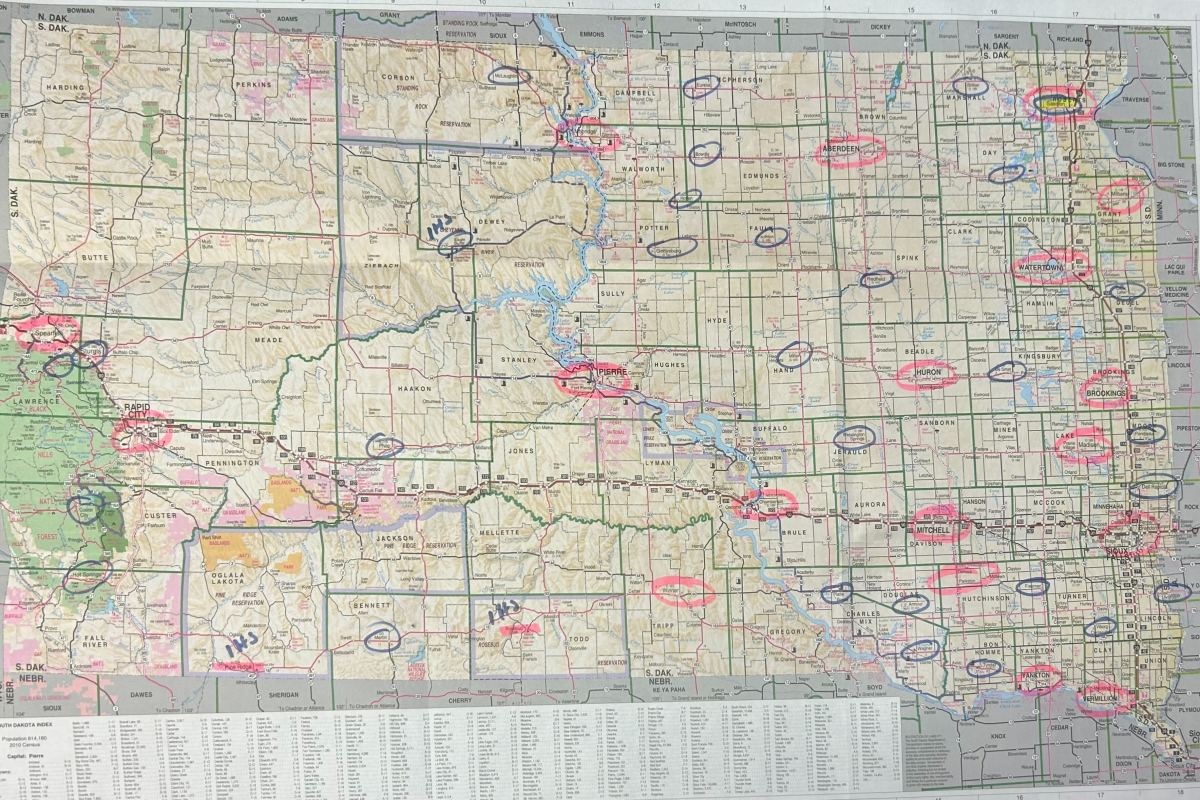

With the closure of Coteau Des Prairies’ OB-GYN services, women looking for specialized care on the Lake Traverse Reservation now have to travel either to Watertown, South Dakota, Sioux Falls, South Dakota, or Fargo, North Dakota. Such a long commute is one of the hallmarks of a maternal healthcare desert, an issue affecting many rural areas across South Dakota and the United States.

Nearly 25 percent of South Dakota women live over 30 minutes away from a birthing hospital compared to a 10 percent nationwide average. Western South Dakota reservations experience abnormally long commute times to birthing centers, sometimes over 118 miles, or 128 minutes.

A lack of access to specialized maternal healthcare has been shown to lead to higher rates of poor birthing outcomes such as preterm births and infant and maternal mortality. Indigenous women in South Dakota already experience disproportionate rates of negative birth outcomes.

According to the South Dakota Department of Public Health, Indigenous women accounted for 46 percent of the pregnancy-associated deaths in the state from 2012-2021, despite accounting for only 9 percent of the state’s total population.

While access to specialized care decreases, birth rates on reservations continue to rise. On the Lake Traverse Reservation, the birth rate was 1.5 times higher than the United States average and the rate of births among women ages 25-29 is double the United States average. On the Standing Rock Reservation, where some women experience commutes of over 118 miles to the nearest birthing center, the rate of births is 20 percent higher than the national average.

After deciding to close the Coteau Des Prairies OB-GYN Department, Kantos said hospital administrators reached out to representatives from local and tribal police departments, emergency services, the local IHS clinic and all hospitals between Watertown and Fargo to inform them.

“We met with the goal of discussing what we do in inclement weather. In some parts of the state the interstate closes periodically, and we’ve been told that if we need to get people out we can,” Kantos said. “We’ve asked the tribe about potential hotel vouchers for tribal families who need to leave in inclement weather, but we haven’t heard back about if that’s doable or not.”

When it comes to emergency births and the need to drive over an hour to receive care, many Indigenous people are less likely to have a reliable form of transportation. With an increased need to travel for specialized OB-GYN services, tribally operated resources are bracing for an increase in home births and support.

“We’re taking steps to adapt to this. One of the changes we’re planning for is having some of my core visitors including myself become doulas and attend doula training,” said Leona Iyarpeya, a Sisseton Wahpeton Oyate citizen and manager of her tribe’s Tribal Maternal, Infant, and Early Childhood Home Visiting Program. “I think we’re pretty prepared, but I do see that number increasing and hitting the 40 marker as one of our services is transportation.”

Iyarpeya’s program provides items like phone cards, diapers and support services, as well as transportation to pregnant women, expectant fathers and parents, and caregivers of children under 5 years old. Families don’t need to be enrolled citizens to benefit from the program.

Travel itself poses a risk to mothers seeking healthcare. Not only is cost often an issue, but travel-related deaths are a risk not accounted for in the maternal mortality rate.

“Typically when we determine maternal mortality, we don’t consider accidents,” said Dr. Lyle Best, a former healthcare physician who worked with the Great Plains Area Indian Health Service for over two decades. “If you’re pregnant and you’re in a car accident and die, that’s not maternal mortality. (In the 1990s) we had a situation in Indian Health Services where a woman was being transferred to Sioux Falls and the plane crashed. The woman was killed and the pilot was badly wounded. Is that considered maternal mortality? She wouldn’t have been on the plane if she wasn’t pregnant.”

Obstetrics doesn’t generate a lot of revenue for hospitals, especially those in rural communities. Kantos said 45 babies were born at Coteau Des Prairies in 2023, and the hospital only had one obstetrics provider during that time. Half of the counties in the United States lack an obstetrics provider, according to a report from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

“It’s difficult for many rural places to provide obstetrics services. It doesn’t generate a lot of money, and it’s hard to find physicians who want to work in a small town and take on that added responsibility,” Best said. “Obstetrics is a terrifying experience, it generally goes well and it’s a happy time but as someone who has been there for hundreds of deliveries your stomach is in a bit of butterflies trying to think of what would happen if, heaven forbid, you lost either the baby or the mother.”

While maternal mortality rates continue to rise across the United States, Indigenous mothers remain the most at risk of dying during or after pregnancy. Indigenous mothers across the United States are two times more likely to die from pregnancy complications than white mothers, according to the CDC.

Hypertensive disorders such as pre-eclampsia are the leading cause of maternal deaths in developed countries. Pre-eclampsia affects between 5-8 percent of all pregnancies. Indigenous people are rarely included in studies focused on pre-eclampsia.

Research in general is limited when it comes to Indigenous mothers and pregnancy complications. Best is currently working to research conditions like pre-eclampsia, though he’s faced barriers when obtaining records and data in areas with large Indigenous populations.

What is known about the increased risk that Indigenous mothers face when giving birth is that the social environment plays a major role. Living in a rural community with a lack of reliable transportation, specialized services and social deprivation affect the population deeply.

“The medical environment can sometimes lead to perhaps having less than adequate care through either Indian Health Services or other facilities they may depend on, and there’s probably some implicit bias or racism involved in the medical decisions that get made,” Best said. “But it doesn’t take a genius to understand that the American Indian maternal mortality rate is not in line with their portion of the South Dakota population.”

As Coteau Des Prairies discontinues its obstetrics services, Kantos emphasized that a majority of medical needs can be covered by family medicine.

“Even though obstetrics will be closed, we will still do general OB-GYN services. We’ll still continue with the full gambit of family medicine and wellness checks. We know we can still do it,” Kantos said.

External

Identification not yet made

With crime rates dropping, a Native lawmaker is concerned over priorities

UTTC International Powwow attendees share their rules for a fun and considerate event

Radio collaboration highlights importance of cooperation in a season of funding cuts for local media

A memorial in the Snow County Prison, now the United Tribes Technical College campus