Rows of ranch-style homes line the streets of Lakota Homes Community, established in North Rapid in 1969.

Photo Courtesy: Vantage Point Historical Services

Native voters in Rapid City, S.D. will have a greater chance of electing a candidate who represents their interests in 2022. Lakota voting rights advocates say that’s due to their novel strategy used during last year’s mandatory legislative redistricting process.

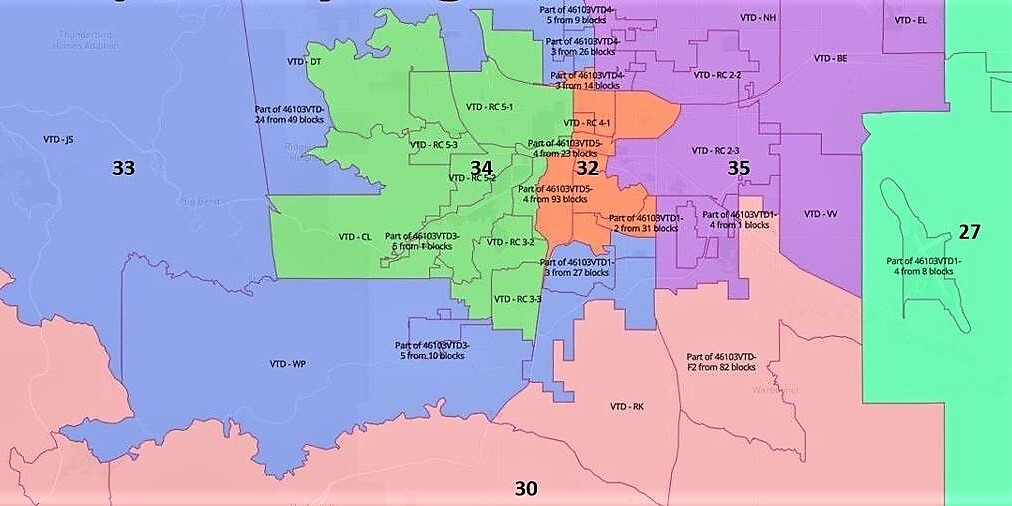

The strategy produced a new voting boundary map that notably groups the previously split Native “community of interest” in Rapid City. Voting rights advocates created a 23.9 percent Native voting-age district in a city that is about 17 percent Indigenous.

The progress in Rapid City was exceptional for urban redistricting nationwide, Native American Rights Fund attorney Samantha Kelty told Buffalo’s Fire. That stems from the fact that Rapid City’s Native residential area is fairly “geographically compact” — a requisite to forming an electoral district.

Most Native urban areas generally aren’t concentrated in a specific geographic area, Kelty said.

In addition, population growth in Rapid City required creating an extra legislative district. Local voting rights champions worked to harness the Native urban voting power. They used innovative computer software to map political boundary options to lobby for a new voting district.

“It provides a lot of hope. It was a compromise that required people to work together in the best interest of the public.”

Kellen Returns From Scout, Great Plains Tribal Chairman’s Association

Leaders of South Dakota’s largest minority voting bloc did not secure all they wanted but came close. With help from the Native American Voting Rights Coalition, or NAVRC, they proposed that 38 percent of Rapid City’s newly created District 32 consist of Native voters.

The bid failed in the state’s Senate Redistricting Committee. Instead, the Legislature approved a different set of boundaries on Nov. 10. Lawmakers procured the governor’s signature the same day. Now, another decade must pass before new legislative districts will be redrawn to assure fair electoral representation.

“Maybe in the next 10 years they can do something,” said Kelty, who helped draw the new District 32. The Native American Voting Rights Coalition – created by NARF in 2015 — took on its first-ever national redistricting project for Native America in 2021.

Golden Opportunity

Redistricting is based on the results of the federal decennial population census. Urban population growth reported in the 2020 U.S. Census qualified each of South Dakota’s two biggest cities to gain a district, Sioux Falls and Rapid City. Lobbyists of all sorts tried to redraw Rapid City based on their interests. They knew the law favors a deviation of no more than 10 percent between the smallest and largest district populations, encouraging roughly equal numbers of residents in each. Native-vote proponents labored well into the eleventh hour to secure a Native voting district.

“I’ve never worked so hard pre-litigation in my life,” Kelty said. Her organization was among several ready to sue the state if the legislators failed to take Native voters into account. State representatives showed they were willing to just barely meet their duties under the Voting Rights Act, said Kelty. They were “not willing to go even one inch further, as they could have done in Rapid City to give a disenfranchised group a voice.”

Rapid City has a population of 74,703 residents. The new district in the center of the city now includes 26,547 voters. District 32 stretches from the historically Lakota neighborhoods of Robbinsdale and Star Village on the south, to Osh Kosh in the center and Lakota Community Homes on the north.

“This map provides at least a small outlet. This is a good start,” said Kellen Returns From Scout, a Standing Rock Sioux citizen who lobbied on behalf of the Great Plains Tribal Chairmen’s Association. “It provides a lot of hope. It was a compromise that required people to work together in the best interest of the public.”

Oglala Lakota citizen and District 27 Rep. Peri Pourier called the remap “a crucial win for Native American representation.” Her rural district’s Oglala Lakota Sen. Red Dawn Foster said the adjusted political boundaries could give the urban Indian community “the chance to have a voice and to have collective representation.”

O.J. Semans, co-executive director of South Dakota’s Native-led Four Directions non-profit, considered the outcome could lead to electing a minority lawmaker to a House seat. It “gave our relatives in Rapid City more voting clout,” he said. In addition, voting districts remained intact in reservation areas, Semans said.

Perseverance Prevails

A citizen and resident of the Rosebud Sioux Reservation, Semans characterized Native participation in the redistricting process as “a lot of hard work, many meetings, a lot of miles traveled.” He said a spokesperson for Four Directions attended every committee and sub-committee meeting on redistricting in the state, providing written and oral testimony.

Likewise, Returns From Scout said he submitted written recommendations to the House and Senate Legislative Redistricting Committees and testified at their hearings. He worked with Rosebud Sioux District 26 Sen. Troy Heinert to provide the committees with a map option that reflected their communities of interest. South Dakota is among many states that require communities of interest to be considered in mapping. It defines them as groups of people with common sets of concerns that may be affected by the legislation. Examples are ethnic, racial, and economic groups.

A number of lawmakers on the committees had little experience in redistricting; some had never visited any of the state’s nine reservations. “They weren’t seeing it from the perspective that political voice could be diluted,” Returns From Scout said. “We needed an advocate.”

He doggedly insisted on rectifying Rapid City district lines to achieve better balance. “His passion went a long way,” Kelty said. “It’s hard to get folks’ attention on redistricting, but it’s almost more important than your vote. If you get a raw deal, your vote could mean half as much.”

“People said time and time again it wasn’t intentional, but for 30 years — a whole generation — we felt we didn’t have a voice. The representation that is afforded to other groups has eluded the Native American community in Rapid City.”

Kellen Returns From Scout, Great Plains Tribal Chairman’s Association

Trailblazing Tool

Heightened Native participation in the redistricting process and the Native American Voting Rights Coalition’s expert technical assistance helped usher in a new district that recognized urban Natives. But a third factor – new mapping software — merits equal credit.

The Native American Rights Fund hired a demographer with her own redistricting program to assist tribal citizens’ work. Plus the group was able to use a free and innovative computer software package made available to the public. Dave’s Redistricting Application, or DRA2020, enabled even amateurs to fiddle with boundary lines and equations. The program empowered ordinary citizens across all 50 U.S. states to craft and propose alternative maps to lawmakers.

In South Dakota, the redistricting committees refused to share their proprietary mapping database with the public. They cited fear of receiving too many proposals and not enough time. The Native American Rights Fund demographer and DRA2020 toppled the obstacle to mapping access.

The public app originated with a team of volunteers claiming mutual “passion for technology and democracy.” Their product was the outcome of a mission to help civic organizations and activists “advocate for fair congressional and legislative districts and increased transparency in the redistricting process.”

Reservation Districts

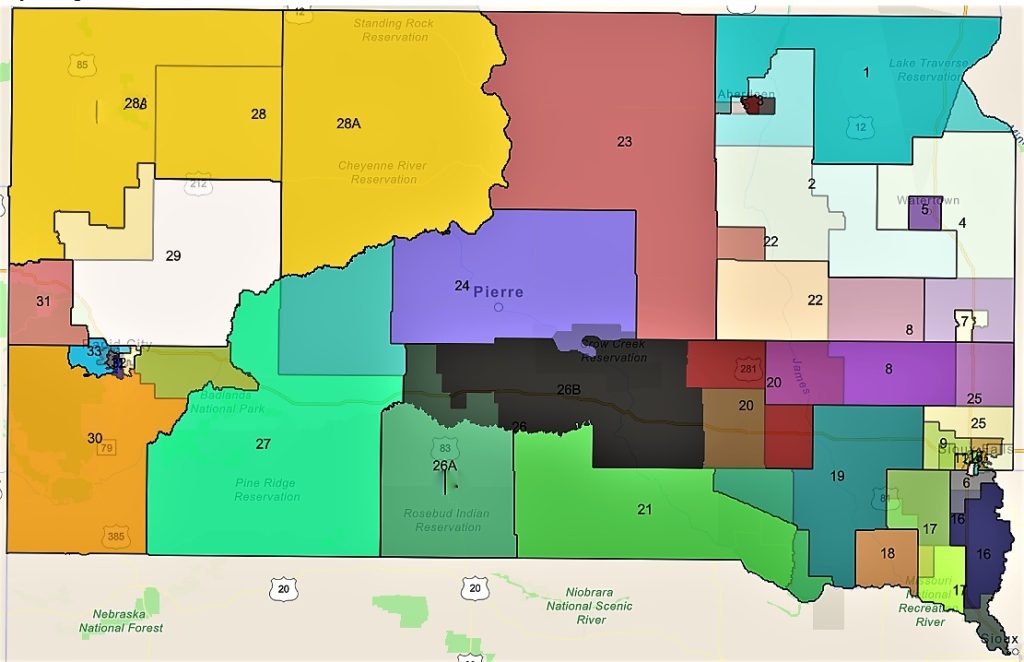

The Native American Rights Fund’s initial focus in South Dakota was on redrawing the rural districts that encompass Crow Creek, Cheyenne River, Standing Rock, Pine Ridge, and Rosebud Sioux reservations. The goal was to respect established district boundaries despite census results of reduced population.

The outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic and associated protocols forced the census to start late, truncating the enumeration, tally, and analysis nationwide. The impact was especially pronounced in Native America. Tribal leaders pointed to other federal statistics and their own enrollment data showing higher population numbers.

In the end, legislators expanded some of the majority-Native district boundaries to include more people living outside tribal lands. This drove down the percentage of Native voters in certain districts. However, those of most notable concern retained their majority of minority voters: Rosebud Reservation with 53.4 percent and Pine Ridge Reservation with 67.7 percent.

South Dakota’s Native vote constituents in previous years have taken their battle to court to achieve just representation. The state, for more than 30 years, ignored federal law meant to protect American Indians from voting discrimination. READ BUFFALO’S FIRE REPORTING ON THIS.

As a result, federal intervention at the outset of the 21st century boosted rural Native representation in the statehouse. But it didn’t help the urban Native constituency. After the latest revision of voting districts, the rally for legislative representation in South Dakota now centers on the urban front.

“In every election since 1990, North Rapid has been divided,” Returns From Scout told Buffalo’s Fire. I was born and raised in North Rapid. My family and friends all still live there, and we’ve never had representation growing up there,” he said.

“People said time and time again it wasn’t intentional, but for 30 years — a whole generation — we felt we didn’t have a voice. The representation that is afforded to other groups has eluded the Native American community in Rapid City.”

The predicament predates Returns From Scout’s memory. Throughout history, families of various tribes camped here on the banks of the Mniluzahan, or Rapid Creek, a feature that inspired the name. In the early 1900s families with children, who were forcibly enrolled at the Rapid City Indian Boarding School, set up a shelter in tents, boxcars, and shacks under the cottonwoods along the creek, according to historian Eric Zimmer.

Photo Courtesy: Kellen Returns From Scout

Some chose to live at the centrally located Osh Kosh Camp because a lumber company there provided jobs.

In the 1930s, a mayoral committee relocated them south to the Robbinsdale area and north to a designated Sioux Addition. In 1969, the Sioux Addition Civic Association attained an expansion with the Lakota Homes Community. The bulk of the Native vote emanates from these magnets in the north.

While growing up in Rapid City, Returns From Scout observed that many of his Lakota peers were largely “numb to the process” of electoral politics — due to historical omission. They experienced sidelining as a result of the state’s reluctance to include tribal people’s input. Omission became typified by gerrymandering and limited voter access to polling places, he said.

Residents have been unable to “make elected officials accountable to our voters, and there’s a reason why. We never had that because our neighborhoods were split up,” he said. Native votes were diluted by separating them into three districts. “It doesn’t take a specialist to look at the way these lines have been drawn not to represent brown people in our city,” he said. “The clock was ticking. It warranted a remedy.”

The new map provides a means “to give our kids an opportunity to dream about or at least strive to” take a place in state lawmaking, he said. Additionally, it may lead to beneficial changes in city council and school district apportionment, he noted. “This provides a pretty good incentive.”

Talli Nauman is an editor at Buffalo’s Fire. To reach her, email buffalo.gal10(at)gmail.com

SOLUTIONS JOURNALISM NETWORK supported this article in the quest to promote “rigorous reporting about how people are responding to social problems.”