Inspired by her grandparents, Tonah Fishinghawk-Chavez proves that caring for the community is an action, not just a word

‘Pushed out’: Two-Spirit student leaves St. Labre Indian School

The school is a private, faith-based school that now serves around 270 students from daycare through 12th grade just outside the Northern Cheyenne Reservation

Nora Mabie

Missoulian

Sully Montoya, 18, stands for a portrait at Hardin High School on April 3 in Montana. Montoya identifies as Two-Spirit, which refers to Indigenous people who fulfill a traditional third gender. (Antonio Ibarra-Olivares, Missoulian)

When Solomon “Sully” Montoya got dressed for school one morning in October 2022, he knew there was going to be trouble.

Standing 5 feet, 10 inches tall (or 6-feet-3 in heels), Montoya carries himself with confidence. He wears a thick beard, and his dark hair falls just below his shoulders. His large brown eyes are accentuated by long lashes.

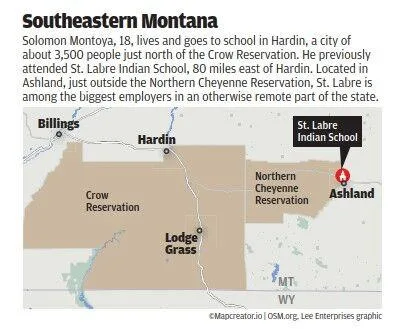

Montoya, who was 17 at the time, attended St. Labre Indian School, a Catholic school just outside the Northern Cheyenne Reservation. Located in southeastern Montana, St. Labre is among the biggest employers in the remote area. Its sprawling campus resembles a small city in the otherwise rural landscape.

The school, which serves primarily Crow and Northern Cheyenne children, has a dress code requiring students to wear polo shirts and trousers, slacks, skirts or other properly fitting pants. But on certain days or weeks, students can evade the dress code by dressing in encouraged themes.

Red Ribbon Week in October was one such week. During Red Ribbon Week, which is aimed at promoting drug- and alcohol-free behavior, students attended specific events and were encouraged to wear college logo gear, ribbon skirts and shirts, the color red, crazy hats and “dress for success” on corresponding days of the week.

Montoya is Two-Spirit, which refers to Indigenous people who fulfill a traditional third gender. For him, being Two-Spirit means, “I don’t just have a masculine spirit or a boy spirit. I also have a feminine or female spirit inside me.” Tribes nationwide have documented prominent Two-Spirit community members for centuries.

On the day students were encouraged to wear ribbon skirts or shirts, Montoya, who is Crow and uses he/him pronouns, chose to wear a pale green, pink and blue ribbon skirt that his mother made. He paired it with heels and a white T-shirt. And he brought a pair of ribbon pants — just in case. Before he made it to his first-period classroom, Montoya was called into the office.

“They told me that I’m not allowed to wear that,” he said. “I asked, ‘Why?’ and they told me, ‘It’s because I’m a male and males aren’t allowed to wear skirts.’ I told them, ‘Today’s a ribbon skirt day, and it’s part of my culture. I’m allowed to wear this.’”

When administrators told him to change clothes, Montoya tried to negotiate. He put on the ribbon pants his mother made, but he kept the heels. He said he was again told he wasn’t allowed to wear the shoes “because you’re a guy.”

Montoya sat in in-school suspension that day and went home for the rest of the week on out-of-school suspension.

Curtis Yarlott, the executive director of St. Labre Indian School, said he would not specifically comment on Montoya but added the situation “goes back to mutual respect.”

“We have our rules,” Yarlott said. “We have our expectations. It’s a two-way street. We ask that students and employees respect those, just as we respect them as people and who they are.

“We don’t try to change people,” he added. “But it’s a two-way street.”

Ten months earlier, in January, the Roman Catholic Diocese of Great Falls-Billings issued a Biological Identity Policy outlining guidelines for students “diagnosed with gender dysphoria.”

The policy, which applies to St. Labre as a school within the diocese, states that such students should not be denied admission to a Catholic school.

It also provides examples, saying students will be addressed with pronouns “in accord with their biological sex,” all correspondence “will reflect the student or parent’s biological sex,” and students will participate in athletics according to their biological sex. The policy states, “all students shall present themselves in their appearance and attire which corresponds with their biological sex,” and students who do not comply “may be dismissed from the school or program.”

Montoya said administrators at St. Labre made him aware of the policy as soon as it took effect.

“It makes me feel like I can’t express who I truly want to be,” he said. “It makes me feel that they can’t accept me.”

Founded in 1884 by a group of Catholic Ursuline Sisters from Ohio, St. Labre Indian School is a private, faith-based school that now serves around 270 students from day care through 12th grade, and older students have the option to board.

Privately funded by donors, the school is free to attend and features a fitness center, thrift store, food pantry, group home and health clinic and provides three meals and plenty of snacks each day. St. Labre boasts a 90% graduation rate — significantly higher than the 68% graduation rate of Native students in Montana public schools — and the school offers scholarships to support some students who go on to college.

According to the school’s mission statement, St. Labre provides “quality education which celebrates our Catholic faith and embraces Native American cultures.” But what happens when tenets of Catholicism clash with Indigenous culture — like in the case of Montoya and his ribbon skirt?

Batées

Long before Catholic influence, since time immemorial, the Crow people recognized three genders — man (bacheé), woman (bía) and Two-Spirit (batée). The Crow language lacks a third-person pronoun, so the issue of genders was not complicated linguistically or culturally.

Men often hunted and fought in war. Women were medicine carriers, property owners, athletes, healers and culture keepers, and participated in ceremonies. Plains tribes also had what’s called “manly-hearted women,” who took on masculine roles, sometimes fighting alongside their husbands in war.

In the 1830s, Crow leader Bíawacheeitchish, or Woman Chief, rose to the level of the third chief in her band of 180 lodges. She hunted for her family, and when her father died, she took over as the protector. Woman Chief took a wife, as she did not do women’s work, and later, she took three more wives, a sign of honor for warriors.

“She wasn’t shunned for that,” said Janine Pease, who has done extensive research on Crow women warriors and is the founding president of Little Big Horn College. “She was recognized and accepted and appreciated for that.”

Batées (pronounced b-uh-dahs) were seen as holy, spiritual people who had great power and deserved respect. They had special roles during the Sun Dance, a ceremony bringing community members together to heal and pray. Tim McCleary, a department head at Little Big Horn College, said the batée would sometimes hide during such ceremonies, not because they were ashamed of their identity, but because they wanted to be seen only as the gender with which they identified.

A Crow warrior known as Osh-Tisch, who earned the name Finds Them And Kills Them, was a famous batée, who lived well into the reservation period. Born a male, according to her own account, Finds Them And Kills Them said she was inclined to be a woman. She dressed as a woman, learned to cook and furnish teepees, and was a medicine person.

But the federal agents and missionaries who came to assimilate the Crows condemned her. McCleary said Finds Them And Kills Them became “an oddity to the non-Indians that came to the reservation.”

Pease said an agent seized her, while others cut her hair and forced her to do manual labor as punishment for her identity. A tribal leader intervened on her behalf, and Crow Chief Pretty Eagle helped get the agent removed.

“(Pretty Eagle) went to (the agent’s) office and said, ‘Leave her alone,’” McCleary said. “That’s (the batée’s) right. That’s who they are.”

McCleary said when Crow children were rounded up to attend boarding schools, one child was a batée.

He said when school officials in Crow Agency realized the child was biologically male, they cut her hair and made her wear male clothes.

“The other children, they objected,” he said. “They said, ‘That’s who she is.’ Eventually, she felt so tortured by the school personnel that she just ran away. Her family, who lived in Pryor, just moved around so that she could never be brought back to the school.”

While batées had cultural and spiritual roles, they began to face more prejudice and discrimination as Christianity rose.

“When I first moved here 30 years ago, people might joke about batée, but they never threatened them or beat them up for being batée,” said McCleary. “But I know now that some are being threatened. It’s changed.”

While being Two-Spirit is not synonymous with being transgender, lawmakers this legislative session have brought several bills that would impact transgender Montanans and the broader LGBTQ community. One bill, signed by Gov. Greg Gianforte Friday, would ban gender-affirming care for trans minors, another would define sex as only male and female in Montana and another sought to ban minors from attending drag shows.

These bills are expected to pass with only Republican support, and earlier this week, Republicans voted to ban Rep. Zooey Zephyr, the first trans woman lawmaker in Montana, from the House floor for the remainder of the session. Bills like these are being proposed in statehouses nationwide, and Montoya is not alone in fighting a school policy that he says clashes with his identity. A network of charter schools in North Carolina has a policy prohibiting male students from wearing long hair, though many Native Americans, regardless of gender, wear their hair long for cultural and religious reasons. The Native American Rights Fund intervened and urged the school to “permanently remove the discriminatory and outdated assimilationist policy.”

‘I felt free’

The Crow negotiated with the Catholic Church for centuries, and recently, the church has continued to make some concessions. The Pope issued a formal apology in Canada last summer for the harm done to Indigenous people, families and communities in boarding schools. And earlier this spring, the Vatican denounced the Doctrine of Discovery, which legitimized the colonial-era seizure of Native lands.

While tribal leaders have said these actions symbolize progress, many say they don’t go far enough.

And on an individual level, people like Montoya are still trying to bargain with the church, just as his Crow ancestors did before him.

Yarlott said St. Labre treats students with “respect and love … regardless of their orientation or their identity.”

He also said the school is working to acknowledge past atrocities from the boarding school era while also looking forward.

“There are individuals within the church who did terrible things,” he said. “And they should not be defended. And the Catholic Church, I think its misstep was in not sooner recognizing that and taking steps to atone for it.”

Yarlott said the school has supported students over the years who identify as Two-Spirit or LGBTQ.

“And in some of those instances, the parents or guardians of those students indicated that they purposely chose St. Labre because they knew we would keep their child safe,” he said. “And we have.”

Montoya’s family chose Labre for exactly that reason. His older sister, Feather Magpie, graduated from St. Labre in 2014 and said she had a great experience at the school, describing the community as “one big family.” Their mother also went to Labre, and Magpie said when the family considered which school Montoya should attend, they were concerned about bullying.

“I didn’t want my little brother to end up bullied to the point where he’d consider suicide,” Magpie said. “I was deathly scared of that. He chose Labre because we thought at Labre, he’d be safe. We thought he wouldn’t have to worry about being bullied for who he is.”

At the time, Magpie said Labre seemed like the best option. So good, that the family agreed Montoya would take the bus 80 miles from their home in Hardin to school every Sunday evening, stay in the dorms, and come home the following Friday afternoon.

While Montoya’s mother and sister worried about how peers might treat him, they hadn’t considered that an administration might cause issues. Magpie said she and her mother explained to Montoya that because Labre is a Catholic school, it may have certain rules, and Montoya said he understood.

“We just didn’t think they’d be so strict,” Magpie explained. “It kind of just seemed like they were pulling rules out of a hat.” She added that had her family known the struggles Montoya would face at Labre, they would never have chosen to enroll him there.

Montoya said when he’d ask administrators at St. Labre why they “were calling him out,” they’d tell him, “’It’s because we care about you, and we want you to have a future.’”

“They’d say things like, ‘You won’t get anywhere looking like that,’” Montoya recalled.

Montoya said comments like these made him feel bad about himself. And sometimes, he’d wonder whether they were right.

“Is the real world going to be like that?” Montoya would wonder. “Or am I going to be accepted in the workplace and not have to deal with bad things?”

Students and teachers throughout the school year supported Montoya and advocated to the administration that he should be allowed to express himself how he wishes.

A teacher who wished to remain anonymous said Montoya was “a good student.”

“He comes from cultural people,” the teacher said. “He was expressing culture through the way he dressed and the jewelry he wore. (The school) makes decisions I don’t really understand.”

In January, Montoya wore his yellow cheerleading sweater, knee-high boots and a bow in his hair to school.

Again, he was called into the office before first period, where he said he was told to change. His boots were too high, earrings too long, makeup too bold.

When his mother came to pick him up from school that day, she unenrolled him.

Montoya, now 18 and a junior, would have to say goodbye to his friends and start over at a new school 80 miles away. As dorm president at St. Labre, Montoya had been planning a winter formal, organizing food, music and activities. But now, he’d only see photos of the event on social media.

Magpie said in unenrolling at Labre, her brother would miss out on educational opportunities, too.

“If he would’ve graduated from Labre, he would’ve gotten a scholarship,” she said. “Not that he can’t still get that, but it would’ve been more of a sure thing at Labre.”

According to Yarlott, St. Labre graduates are eligible for scholarships to support their postsecondary education, whether that be at a college, university or trade school. The school also employs a full-time mentor to support graduates as they pursue opportunities in higher education.

Magpie said she’s also upset her brother will be disconnected from a community of peers he cares about and who care about him.

“My brother’s presence at Labre was so big,” she said. “Enormous. Everyone loved him. He didn’t have problems with teachers or students. So I feel like he’s missing out on being with all the people he had to leave behind. The people he was close with.”

Montoya said he felt “pushed out.”

“It makes the school a less diverse place,” he said of Labre. “It shows that the school … only supports (a certain) type of student, and only this type of student will achieve, while they push all the others out.”

But when he unenrolled, Montoya also felt relief.

“I felt free,” he said.

Montoya now attends Hardin High School, a public school that serves about 500 students. He joined the drama club and a group that helps do good deeds in the school and around the community. He got his driver’s license and started working as a cashier at a rest stop.

Dressed in a pale blue sweater, pearl necklace, heeled knee-high boots and clip-on bangs, Montoya smiled when asked if he is happy at Hardin.

“I like it a whole lot better,” he said. “I get to express myself the way I always wanted to — the way I never got to at Labre. I have a future at Hardin.”

The Catholics and the Crows Nora Mabie

The first documented Catholic influence on the Crow people was in the mid-1800s. Vance Crooked Arm, a Crow studies instructor at Little Big Horn College, said Father Pierre-Jean De Smet visited the Crow people with a pipe, which held significance in Crow culture. De Smet, a Jesuit known to wear a black robe and sandals, lit a match — something Crow people had not yet seen — and smoked the pipe. The Crows were astonished. “Crows saw him as like a God,” Crooked Arm said. In the early days of missionaries, the Crow people found commonality and respected their spirituality and thought. But by 1868, when the reservation was formed, Crooked Arm said the Crow people had enough exposure to missionaries to realize that Christianity was a unique spiritual form. As the federal government began implementing boarding schools nationwide, Crow chiefs negotiated, insisting that the schools be on reservation land. If children had to attend these schools, at least they’d still be near their families and community. Soon, there were three boarding schools that served Crow children — one in Crow Agency, one in Pryor and one in St. Xavier. Tim McCleary, a department head at Little Big Horn College in Crow Agency, said the boarding schools “aggressively” recruited children to attend. “They’d physically grab them and take them to school,” he said. “In fact, it was the job of the Indian police to gather the children.” Some parents would be beaten if they resisted, and agents, with support from Congress, would withhold food rations from families that did not comply. In 1887, St. Xavier Mission served 50 children. A year later, the student body tripled to 144. Janine Pease, founding president of Little Big Horn College who has done extensive research on boarding schools, said attendance was mandatory. “If you don’t have food, you’re not going to think twice about having your kids go to school,” said Pease, adding that conditions on the reservation were already dire as disease spread. “Families have to exist. This is serious stuff. This is abject starvation.” McCleary said Crow Chief Pretty Eagle converted to Catholicism in the late 1880s, giving him some leverage. If he heard of children being mistreated or abused, he would condemn boarding school leaders. “The idea was that if you could get the chief to convert, then his followers will convert,” McCleary said. “And because of that, Pretty Eagle had a lot of authority at St. Xavier.” Crow people, at the time, didn’t eat fish, so when a boarding school served fish from the Pacific coast, McCleary said the children “freaked out.” Some ran away. Pretty Eagle met with a priest to explain what happened. “They negotiated, and I guess (Pretty Eagle) said, ‘Well, if you’re going to feed them fish, feed them fish from our rivers,’” McCleary recounted. Pease said the Crow also negotiated to visit the schools and see their children on Sundays, whereas other Catholic schools nationwide did not allow parents on the property. The negotiations continued and by 1910, the majority of Crow children were in day schools, not boarding schools, a circumstance unique to their tribe. And in 1920, Pease said the Crow Act passed Congress, setting aside land so children could go to public schools. “The boarding school era was shut down here much earlier,” she explained. “Other tribes didn’t have that privilege. The Cheyennes never had day schools until recently. They had to go to Labre or the boarding school in Busby.” Pease said the Crow were likely better suited to negotiate with the federal government because they had been allies. “The tribes were not just acted upon,” she said. “They acted back.”

This article was first published in the Missouilan.

External

Dramatic play reveals power of Indigenous stories and community

Thousands peacefully protest

With crime rates dropping, a Native lawmaker is concerned over priorities

UTTC International Powwow attendees share their rules for a fun and considerate event

The ceremony also honored players who have passed