The billboard project is expanding to Oregon

Oklahoma governor vetoes bill allowing graduation regalia

Tribal leaders, civil rights advocates urge legislature to override the veto

Richard Arlin Walker

ICT

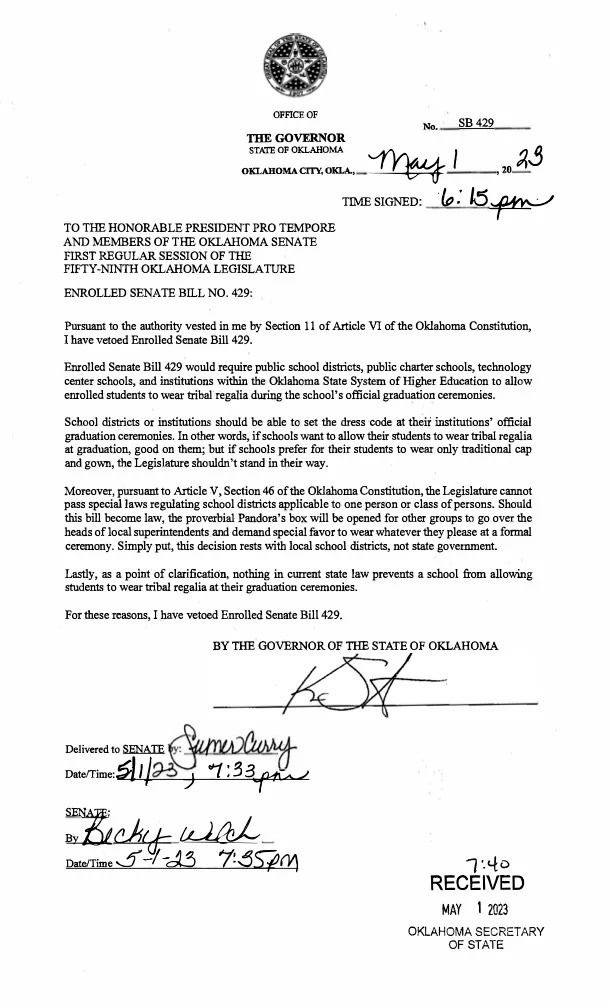

In this file photo, Brailyn Jake wears an eagle feather at her graduation from Cedar City High School in Cedar City, Utah, on May 25, 2022. Utah is among 11 states with laws that specifically protect the right of Indigenous students to wear regalia at graduation ceremonies. On May 1, 2023, Oklahoma Gov. Kevin Stitt vetoed a a bipartisan bill that would have allowed Native students across the state to wear regalia during graduation ceremonies. Tribal leaders are now calling for the Oklahoma legislature to override the veto. (AP Photo/Rick Bowmer)

With one swipe of the pen, Oklahoma Gov. Kevin Stitt vetoed a bipartisan bill that would have allowed Native students to wear tribal regalia at graduation ceremonies.

The move drew a sharp response from tribal leaders – including leaders of the Cherokee Nation, where Stitt’s citizenship remains controversial – and civil rights advocates, who urged the legislature to override the veto.

“Should this bill become law, the proverbial Pandora’s box will be opened for other groups to go over the heads of local superintendents and demand special favor to wear whatever they please at a formal ceremony,” Stitt, a Republican who is enrolled with the Cherokee Nation, said in a statement to lawmakers announcing the veto.

He noted that “nothing in current state law prevents a school from allowing students to wear tribal regalia at their graduation ceremonies.”

Tribal leaders and rights advocates, however, said the bill would have guaranteed that right, as several school districts in Oklahoma already do not allow it.

“When students choose to express the culture and heritage of their respective Nations to signify this moment in their lives, it is not to ‘demand special favor to wear whatever they please,’ it is to honor their identity,” Muscogee (Creek) Nation Chief David Hill said in a statement.

“We must continue to communicate the unique aspect of this honor, and that allowing this expression is in no manner a gateway to introduce chaos and irreverence into formal ceremonies.”

The bill had broad bipartisan support in the state’s Legislature. The state House and Senate education committees unanimously endorsed the bill, known as SB 429, and advanced it to the floor of their respective chambers for a vote. The Senate approved the bill 45-0 on March 22; the House approved it 90-1 on April 24. Stitt vetoed the measure on Monday, May 1.

In Oklahoma, home to many Indigenous nations that were forced to relocate there in the 19th century, the lack of a guaranteed right to wear regalia at graduation is a reminder of past policies that sought to suppress Indigenous culture and force assimilation.

School district policies banning the wearing of Indigenous regalia at graduation ceremonies “compound the violence and oppression that these students and their communities have suffered,” wrote Heather L. Weaver, senior staff attorney for the American Civil Liberties Union’s Program on Freedom of Religion and Belief.

“Students who have resisted these dictates have had their sacred items confiscated or have been excluded from graduation altogether. While a handful of states have passed laws in response to these restrictions, the protections do not always apply to all Indigenous students, and many students still struggle to exercise their rights.”

Indigenous leaders in Oklahoma called for the legislature to override the veto, which would require a two-thirds vote in each house, according to the Oklahoma Senate website.

“This bill would have simply made those rights more clear, so public school administrators do not mistakenly violate them,” Cherokee Nation Chief Chuck Hoskins Jr. tweeted. “That’s why the legislature approved this bill, along with other bills supported by tribes, with nearly unanimous, bipartisan votes. I strongly urge the Legislature to override the governor’s irresponsible vetoes of this and other important legislation.”

Cherokee Nation Principal @ChuckHoskin_Jr issues statement on Governor Stitt’s veto of Native Regalia Bill pic.twitter.com/fwYR0OnA0Z

— Cherokee Nation (@CherokeeNation) May 2, 2023

Choctaw Nation Chief Gary Batton called SB 429 a non-controversial, common-sense measure that would allow Indigenous students to honor their culture.

“We hope the House and the Senate will quickly override the veto to provide more freedom for Oklahoma students who want to honor their heritage,” he said in the statement.

Diana Cournoyer, executive director of the National Indian Education Association, also urged the legislature to override Stitt’s veto and “not let partisan dissension get in the way of protecting the religious and cultural rights of our students.”

Cournoyer added, “An immense amount of pride and respect is shared among students who wish to honor their heritage and communities while they are recognized for their academic achievements. Gov. Stitt’s decision to veto SB 429 sends a clear sign to our Native students that state leadership does not respect the political relationship between the 39 tribal nations and the state of Oklahoma.”

Eleven states — Alaska, Arizona, California, Kansas, Mississippi, Montana, North and South Dakota, Oregon, Utah and Washington — have laws that specifically protect the right of Indigenous students to wear regalia at graduation ceremonies. In the Pacific Northwest, for example, it’s not uncommon to see an Indigenous graduate wearing a mortarboard made of woven cedar and adorned with an eagle feather.

According to the ACLU, the wearing of Indigenous regalia at graduation ceremonies may be protected by religious freedom laws in many states; many Indigenous students believe wearing regalia is an important part of their religious or spiritual practice.

The First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution may also provide protections, “especially where public schools allow other types of adornment for graduation caps and gowns but prohibit tribal regalia,” the ACLU reported.

In addition, the issue may also fall under a federal law known as Title VI that prohibits federally funded schools, either public or private, from discriminating based on race, ethnicity or national origin.

“Even if schools do not intend to discriminate, if their policies disproportionately and negatively affect students of a particular race, ethnicity, or national origin, the policies will likely be considered discriminatory,” according to the ACLU. “School policies that prevent Indigenous students from wearing tribal regalia may violate this law.”

Stitt is a descendant of Cherokee Nation citizen Francis Dawson, but the nation tried to disenroll Dawson in 1900, saying he had falsely stated that he was Indigenous and allegedly bribed witnesses in order to gain access to land allotments in Oklahoma. There is no provision for the Cherokee Nation to disenroll citizens.

External

Identification not yet made

UTTC International Powwow attendees share their rules for a fun and considerate event

Radio collaboration highlights importance of cooperation in a season of funding cuts for local media

A memorial in the Snow County Prison, now the United Tribes Technical College campus

Standing Rock Sioux Tribal Chairwoman Janet Alkire tells crowd, ‘We’re going to rely on each other’