OB-GYN fears, maternity deserts impact health care in North Dakota

Access worst in Native American, rural communities

Michael Standaert

North Dakota News Coorperative

Entryway of the Sanford Fargo Family Birth Center at Sanford Medical Center Fargo. Currently there are only 11 birthing facilities in the state, limiting the options for many rural residents. Photo provided.

Dr. Ana Tobiasz, a maternal-fetal specialist at Sanford Health in Bismarck, said she has contemplated leaving the state because of the state’s abortion ban.

The near total ban on abortions in the state went into effect in late April 2023, which prohibits all abortions except for when the health of the mother is at risk or in cases of rape or incest, but only within the first six weeks of pregnancy.

The initial language of the law was amended to allow terminations of ectopic pregnancies, where a fertilized egg implants outside the uterus and would never lead to a birth.

“The changes that were made were really important, otherwise I would have left immediately,” Tobiasz said.

Tobiasz isn’t alone. Longstanding issues of access to prenatal and maternal care in rural areas have been exacerbated by the state’s abortion ban, a move some obstetricians say has put them on edge over potential legal concerns arising from a termination of pregnancy.

Abortion restrictions in other states have led some OB-GYNs to leave those states, as well as reducing the number of obstetric medical students seeking residencies in those states. It is not known if any OB-GYNs have left North Dakota because of the near total ban.

“I’m not aware of anybody that has left, but I can say that for those of us here trying to care for patients, it has made it much more challenging and scary,” Tobiasz said.

Kali Bauer, executive coordinator at the Minot Women’s Network, said she was also not aware of obstetrician flight, but many have raised concerns about legal ramifications.

“A lot of providers have to defer to their hospitals or attorneys before they can even address a situation, before treating a person who is at risk or if it is going to put the pregnancy at risk,” Bauer said.

The situation now, Tobiasz said, leaves open how the law can be interpreted and could still lead to potential legal challenges for doctors terminating a pregnancy when the life of a mother is at risk.

“I’m not one that advocates for calling a lawyer to make the decision, because at the end of the day, the hospital lawyers are not who are going to represent you in court if you get charged with a crime, and they also don’t have the medical background,” Tobiasz said.

Living in a maternity desert

A drop in the number of available OB-GYNs could further reduce access to care and increase the spread of maternity deserts in the state, those following the situation said.

States where abortion is prohibited, on average, have fewer OB-GYNs than states where abortion rights are upheld – around 92 per 10,000 births compared to 138 per 10,000 – data from the AAMC Research and Action Institute, a think tank of the Association of American Medical Colleges, indicates.

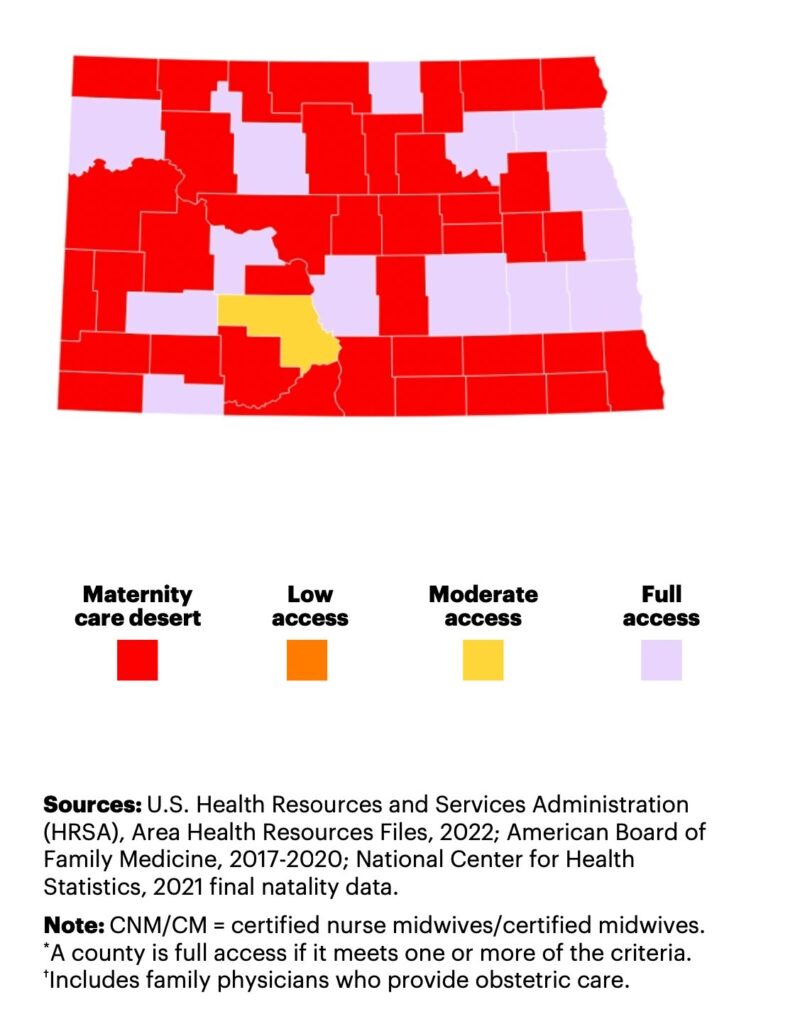

According to a March of Dimes study published last year, 71.7% of counties in North Dakota are considered maternity deserts, where drive times to a birthing hospital are over 30 minutes or more, the highest percentage in the continental United States.

Some areas are over two hours from a birthing hospital. Currently, there are only 11 hospitals in the state where mothers can give birth. Only one of those, Quentin N. Burdick Memorial Hospital in Belcourt, is on a Native American reservation.

“The number of OB-GYNs in these states is already lower, and we know that providers are worried of getting lawsuits against them or fines for providing abortion care, and if those fears impact where they work, then we believe we’ll see changes in the future,” said Ashley Stoneburner, director of research at the March of Dimes.

“It’s kind of scary that the trend could continue in all those states,” Stoneburner said.

One way to address this in rural areas would be to increase the number of midwives or family provider doctors who have obstetric training, but those numbers are low for North Dakota. Currently there are no birth centers in the state fully staffed by midwives, according to Stoneburner.

Least access to care

Native Americans have the highest rates of inadequate access to prenatal care of any group both in maternity deserts and in areas where there is more access, according to the March of Dimes study.

Andrew Williams, a public health professor at the University of North Dakota currently leading a study of stress and health in Native American pregnancies, said around 73% to 75% of Native American women in the state receive prenatal care in the first 13 weeks of pregnancy compared to around 92% to 95% rate of for white women.

Williams said transportation issues, access to child care for children already born and lack of appointments at the right time are the major issues for Native American women and women living in rural areas.

“When it comes down to those communities, it’s not just that they can’t deliver in their community, but oftentimes they’re not getting any type of prenatal care in that community,” Williams said.

Bauer knows a family situation where the husband had to stay behind when his wife was ready to give birth, because they didn’t have anyone to watch their children or the extra money to fork over for a hotel.

“So that’s something that families do have to kind of navigate,” she said.

Maternal mortality

Nationally, maternal death rates have risen from around 14 to 49.2 deaths per 100,000 live births for American Indian and Alaska Natives over the past 20 years, according to the Center for Disease Control (CDC).

“What always strikes me as kind of the most heartbreaking piece around this is that the vast majority of these deaths are preventable, and the vast majority of these morbidity events are preventable, and so it really makes the case for ways that we really need to be reimagining our maternity healthcare system,” said Ruth Richardson, a former Minnesota legislator and now CEO of Planned Parenthood North Central States.

According to the CDC, 93% of maternal deaths among American Indians and Alaska Natives were preventable.

North Dakota has a low infant mortality rate of 4.39 per 1,000 live births and its maternal mortality rate hovers somewhere in the middle of all states at 20.1 per 100,000 births.

Tom Arnold, an OB-GYN in Dickinson is chair of the state’s Maternal Mortality Review Committee. He said there’s a greater problem with things like mental health issues, drug issues and intentional or accidental overdoses leading to these deaths that also need to be addressed beyond the maternity desert factor.

Ten mothers died while pregnant in 2021, and seven in 2022, according to the committee’s data. Of those 17, seven were from homicide, suicide or possible drug overdoses.

Arnold hadn’t seen evidence of OB-GYNs potentially leaving the western edge of the state. He said the situation hadn’t changed all that much since the state’s only abortion clinic was already far away and only moved across the river into Minnesota.

While he imagined there was some fear among some OB-GYNs about potential legal issues, he thought “generally, most of that fear is unfounded, to be honest.” He had not heard of any OB-GYNs getting into trouble for terminating a non-viable pregnancy or doing a surgical procedure for a potentially life-threatening ectopic pregnancy.

The reduction in the number of hospitals with birthing facilities has been happening for years, Arnold said, estimating there were two to three times the number available 35 years ago compared to now.

A lot has to do with the costs of keeping a birthing facility operating with licensed OB-GYNs who can conduct cesareans and maintain an anesthesia unit in the current climate, where a lawsuit could sink the entire hospital.

“If you were in a small hospital that has very few deliveries, the services that are necessary to provide that level of service are sometimes hard to maintain because of the cost,” Arnold said.

A statewide maternity care network that links the 11 hubs where births occur could be a solution, and is somewhat already in place, Arnold said, but could be refined to provide better care in maternity desert areas.

Another possibility is more telehealth for routine checkups, but that can’t be the full answer.

“Obstetrics is not the easiest specialty to do at a distance. We can’t do distance deliveries … because you’re doing things like ultrasounds, and you’re doing laboratory testing during pregnancy that requires direct contact with the patient,” Arnold said.

The North Dakota News Cooperative is a non-profit news organization providing reliable and independent reporting on issues and events that impact the lives of North Dakotans. The organization increases the public’s access to quality journalism and advances news literacy across the state. For more information about NDNC or to make a charitable contribution, please visit newscoopnd.org.