Source/ Google Maps

Each day an estimated 10-15 people risk their lives when they walk or bike across town on the main highway route on the Turtle Mountain Reservation. At least six people have died in the past 15 years. An unknown number of others have been injured on the highway that lacks street lamps.

Even when the temperature is below freezing, pedestrians will still trek through the darkness along the edge of U.S. Highway 281 to move between Dunseith and Belcourt. As the main road that runs through the reservation, the highway remains the only option for many people without cars to get to work or do their errands. In the dark, the road, according to experts, has torn apart many lives.

Besides poor lighting, the highway lacks a path for pedestrians. For Teri Allery, a sustainability energy technologies faculty member at Nueta Hidatsa Sahnish College in New Town, N.D., the deaths hit very close to home. In 2011, a close friend was hit by a car and killed as she was walking along the road about a quarter of a mile past the Sky Dancer Casino and Resort. A year later, half a mile west of Belcourt, her aunt’s vehicle was struck by another vehicle in an accident that killed her. Just a month later, her cousin and another aunt were walking across the road to her grandmother’s house when they were hit by a vehicle.

The losses remained on Allery’s mind and eventually gave her an idea while she was an Indian energy intern at Sandia National Laboratories. She decided to conduct her research on a problem that affected her community. After her loved ones died on the highway, it became apparent to her that the lack of lighting on the highway was a public safety issue.

“I don’t think that they [the US Department of Transportation] take into consideration how many people actually walk on the road,” said Allery. “Some walk from Belcourt to the casino or to [Shell Valley] housing and back.”

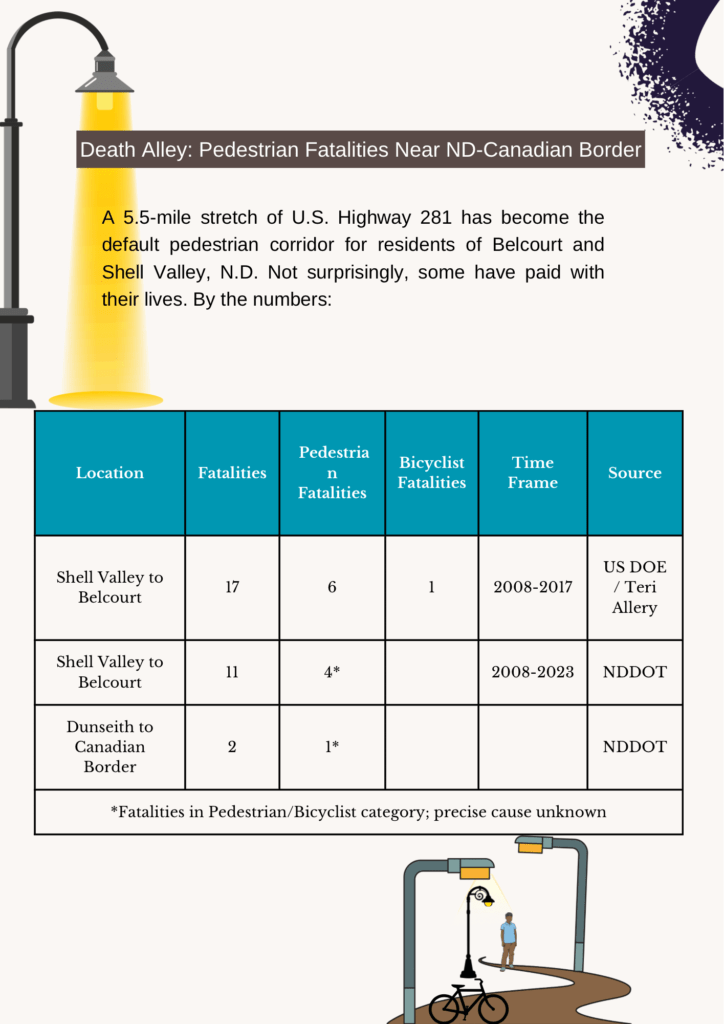

According to a 2018 research paper authored by Allery and published by the U.S. Department of Energy, 17 people lost their lives on U.S. Highway 281 from Shell Valley to Belcourt between 2008 and 2017. The North Dakota Department of Transportation cited 55 crashes on that same stretch of road from Jan. 1, 2008 to Oct. 15, 2023. Of these 55 crashes, 11 fatalities were reported.

Four of those were in the pedestrian/bike category. Between Oct. 1, 2018, and Sept. 30, 2023, eight crashes were reported on Highway 281 from Dunseith to the Canadian border. Of these eight, two fatalities were reported. One of those was in the pedestrian/bike category. Since the state highway passes through tribal land, not all of the fatalities may have been reported to NDDOT.

“It’s a great concern because it really does need lighting in that it is a place where a lot of people walk to get from here to there. It can be quite dangerous because it gets pretty dark in the winter.”

Sandra Begay- Mechanical Engineer at Sandia Labs

The most reported accidents occur along a 5.5-mile stretch between the west end of Belcourt to about a mile past the Sky Dancer Casino and Resort. The Department of Energy reported the accidents are mainly caused by low visibility along the dark highway.

The North Dakota Department of Transportation, or NDDOT, said they currently aren’t aware of a light problem on Highway 281, but they do recognize the need for a pedestrian walking trail. “There is no report of a lighting issue in Dunseith on Highway 281 that we are aware of. If there is an issue with a traffic light or overhead street lights we would like to know so we can address it,” wrote David Finely, the assistant communications director at NDDOT.

Meanwhile, The department has received funding for the Tribal Trails Connection Project to address pedestrian safety issues and improve mobility in the community for those who lack transportation. Right now, NDDOT is planning to build a 6-mile trail along Highway 281 between the Sky Dancer Casino & Resort and the Turtle Mountain Community High School in Belcourt. This project would include installing a shared-use path and a lighting installation.

The money will be used for construction and construction engineering, but not preliminary engineering for the trail. The Tribal Trails Connection Project received the money to address public safety and sustainability issues and to encourage a healthy lifestyle for those in the community. The project would also be funded by federal grants and state funds.

The estimated cost is $6,566,667 for the Tribal Trails Connection Project along Highway 281. A similar NDDOT pedestrian path is also being planned on the Spirit Lake Reservation. According to NDDOT, the two reservation pedestrian projects will use $9,850,000 in Rebuilding American Infrastructure with Sustainability and Equity grants, otherwise known as RAISE.

Meanwhile, Sandra Begay, a Navajo Nation mechanical engineer at Sandia Labs in Albuquerque, N.M., served as Allery’s mentor during her research. She encouraged Allery throughout her road lighting project and advised her to look more at solar lighting.

“So people stop losing their lives because they’re just trying to get from one place to another, sometimes they have no transportation, so the only option is walking.”

Teri Allery- Sustainability Energy Technologies faculty member at Nueta Hidatsa Sahnish College

“I’ve actually been on that road when I was up there,” said Begay. “It’s a great concern because it really does need lighting in that it is a place where a lot of people walk to get from here to there. It can be quite dangerous because it gets pretty dark in the winter.”

After some in-person field visits on the reservation, Allery worked to devise a solution for the area: sustainable lighting options, such as solar street lights with a microgrid, and stand-alone street lights in isolated areas would best address the tribe’s needs. A microgrid can use a traditional electrical grid system or stand-alone. Microgrid systems can be utilized when distribution lines can’t be installed for regulatory or budgetary reasons. A stand-alone power system is a self-generating off-the-grid electricity system for remote locations that can provide energy far from the grid.

Traditional street lights over the 5.5-mile stretch would cost $472,196 including the cost of electricity per year. In contrast, stand-alone street lights would cost $484,000 and solar street lights with a microgrid would cost $7,527,437. Using renewable energy sources, such as solar street lighting, would save the tribe money over time.

In her research, Allery concluded that the best recommendation is for the Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa to install the solar street lights stand-alone systems between mile markers 239 and 245 from Shell Valley to Belcourt on North Dakota Highway 281 since it would be the least expensive over time after the initial installation cost.

Other tribes, such as the Ute Mountain Ute Reservation, have dealt with, and addressed, similar lighting problems. The Colorado Department of Transportation installed more than 200 LED lights along U.S. Highway 160 near Towaoc to enhance nighttime visibility for drivers and pedestrians in 2016.

Though Allery emailed her paper to the chairman of the Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewas, she never presented her research to the council when it was first published in 2018. Since her research concluded, she hasn’t heard about any progress in addressing the lighting issue on the reservation. The Turtle Mountain Reservation Headquarters could not be reached for comment.

Allery agreed the Tribal Trails Connection project is another solution that could prevent deaths, depending if adequate lighting will be provided. “If they were to do a walking or bike path, I think if they had some sort of lighting on the trail, the road would be fine the way it is,” Allery said.

The first part of the Tribal Trails Connection Project along U.S. Highway 281 is planned for construction in 2026.