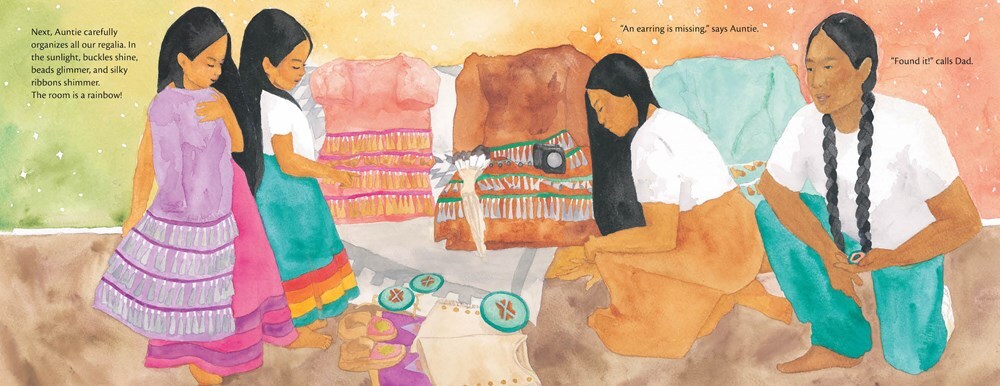

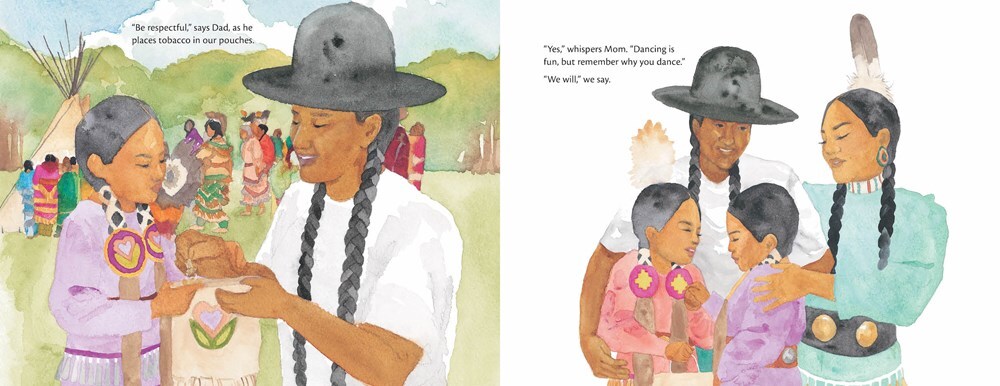

Deidre Havrelock wrote “Why We Dance” to share information of the history and pride of the jingle dress dance. ( Illustrations by Aly McKnight © 2023)

“Why We Dance” is a story that celebrates Indigenous tradition, hope, resilience and unity through the history of jingle dress dancing.

Told from the perspective of a young Indigenous girl, the story of “Why We Dance” focuses on her tender relationships with her mother, aunt, cousin and other relatives in the broader community.

Deidre Havrelock first began brainstorming “Why We Dance” during the COVID-19 pandemic. Since there wasn’t much to do outside of the home at the time, she began watching videos of jingle dress dancers while taking care of her grandson. The author, a citizen of Saddle Lake Cree Nation in Alberta, Calif., has always been interested in the dance because of its intricate moves and beautiful regalia. Growing up, however, her shy nature and the cost of the regalia prevented her from learning the dance.

The jingle dress dance is traced back to the Mille Lacs Band of the Ojibwe Tribe in Minnesota during the early 1900s. The dance would later evolve across Wisconsin, Minnesota and Ontario, Canada, in the 1920s. According to Powwows.com, jingle dress dancing started as a healing ritual.

The story behind the dance is that a medicine man crafted his granddaughter a jingle dress after she became ill. The dress was foretold to heal the granddaughter once she danced in it. At the time, the 1918 to 1920 influenza pandemic was running rampant. The disease devastated Indigenous communities in North America. The pandemic took the lives of thousands of American Indians, especially those living on reservations. Considering how rituals and Indigenous practices were banned in the United States until the American Indian Religious Freedom Act of 1978 and the lifting of the 1927 Indian Act across Canada in 1951, jingle dress dancing became an act of resistance.

Havrelock, who became mesmerized by the dance, found inspiration from learning the history of the practice. The author scheduled an online tour with the Mille Lacs Indian Museum to see some of the regalia and hear the story, and from there decided to write a children’s book on jingle dress dancing.

“I thought, here we are a hundred years later, we’re back in the same situation, dealing with this breakout of COVID and here are these people, these women are dancing again,” said Havrelock.“What caught me is the idea of not only healing but healing through dance and prayer.”

When she first began the writing process, Havrelock said she went into prayer and asked Creator to show her what was missing in her story. Towards the end of the book, the author had a revelation and received the answer to her prayers.

“I had a beautiful dream where Creator showed me that dance is prayer and Creator understands the language,” said Havrelock. “So when I heard that in a dream, I was like, oh, okay, I get it. Dance is the language. I was so caught up in my world of using words, that I was stuck in the idea that there were words involved.”

Havrelock and self-taught watercolor illustrator Aly McKnight bounced ideas back and forth for about a year. They wanted Indigenous students to be able to feel represented and see themselves throughout this lyrical book.

“I really wanted to encapsulate the idea of childhood and the beauty of our Indigenous people with a dreamy yet vivid color palette and my use of watercolor paints was to create an organic and free-flowing effect that would help dance the readers across the page,” McKnight said.

This story in particular holds a lot of significance to McKnight, an enrolled member of the Shoshone-Bannock Tribes. “I grew up in the powwow circle so I got to capture small moments of my childhood within the pages of this book,” said McKnight. “Also my daughter is now a jingle dress dancer and her love for the dance inspired me every step of the way while sketching and painting, so in a way she was my biggest and favorite collaborator.”

The 40-page book, which is aimed at children between first and third grade, is a story that McKnight believes everyone can learn from. “‘Why We Dance’ is a colorful celebration of dance, community, doing things that scare us, and healing,” said McKnight. “It’s a story that I think everyone from every walk of life will find that it changes them and may even heal a part of themselves they didn’t know needed healing.”

After the author completed “Why We Dance,” she realized she wasn’t too old to begin learning how to jingle dress dance. Havrelock recently received her regalia and is planning to learn the dance with her friend within the next few months. She hopes children who are interested in jingle dress dancing will seek opportunities to learn the practice.

“I wanted to write this book to be an encouragement for other little kids to be able to ask their parents,” said Havrelock. “Yes, it’s going to be scary and you’re going to have nerves –– but you can do it.”“Why We Dance” is currently available for pre-order on Abramsbooks.com and will be released to various retailers on Feb. 6. Havrelock’s next picture book, “The Heartbeat Drum,” is also scheduled to come out later this year.

Hedgpeth, D. (2020, September 27). Native American tribes were already being wiped out. Then the 1918 flu hit. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/history/2020/09/28/1918-flu-native-americans-coronavirus/

National Institute of Health. (n.d.). 1978: American Indian freedom of religion legalized. Tribes – Native Voices. https://www.nlm.nih.gov/nativevoices/timeline/545.html

The Ban on Traditions. Niganenakwemin. (n.d.). https://kopiwadan.ca/wisdom/ban-traditions/?lang=en