Native victims of mass execution remembered in Minnesota

Dan Ninham

ICT

The Dakota 38+2 horseback riders battle sub-zero temperatures and snowfall on the way to their stop in Redwood Falls, Minn., Dec. 21, 2022. (Photo courtesy of Casey Ek)

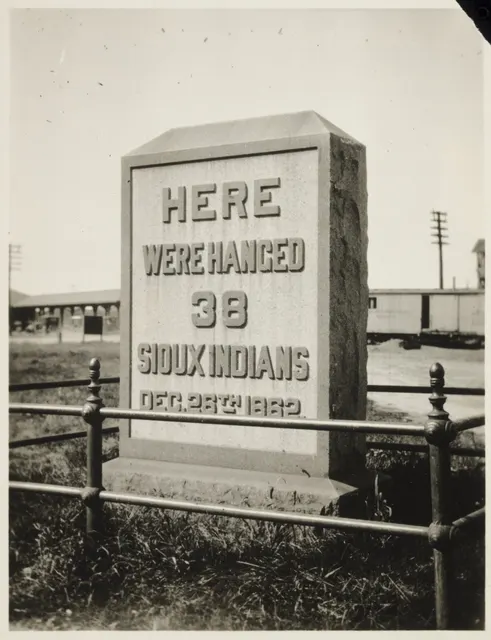

The U.S.-Dakota War of 1862 ended on Dec. 26, 1862, when 38 Dakota men were hanged in Mankato, Minnesota, in the largest mass execution in the country’s history. Two other Dakota were later brought back from Canada and executed.

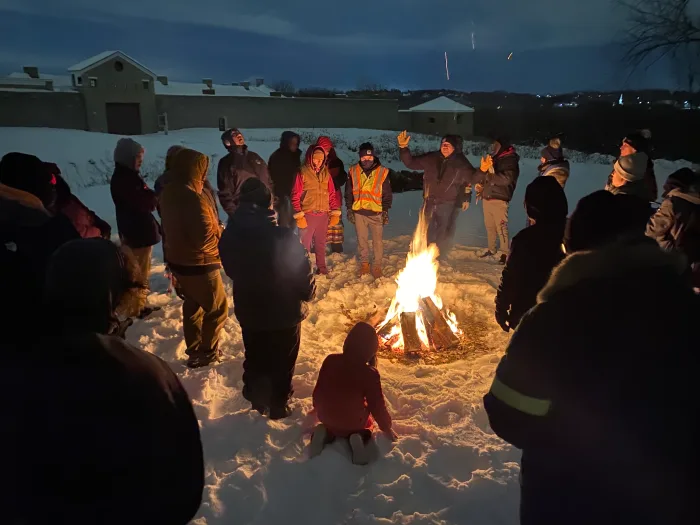

The executions took place in southwestern Minnesota more than 160 years ago but their memory lives on each December through the day after Christmas when many gather in Mankato to honor and remember. Annually, a run and a horseback ride honor the ancestors, often against the brutal Minnesota weather.

An idea in 1983 turned into a collective vision in 1986. The late David Gonzalez, Yaqui, at the time a professor at University of Minnesota and avid distance runner, honored the Dakota 38+2 by organizing a spiritual run from Fort Snelling, Minnesota to Mankato, Minnesota.

Douglas Fairbanks, an Ojibwe competitive runner, connected with Gonzalez to organize the Indian Nations Running Club. After completing the first run from Fort Snelling to Mankato, Fairbanks reflected that Gonzalez predicted the run was going to take place from then on and also there would be horse riders showing up and walkers coming from all directions. This eventually happened.

Fairbanks said he witnessed an earth moving sight when the horse riders came to Mankato and met the runners on Monday, Dec. 26.

“It was like over a hundred years ago. The horses were all moving and making the grass come out of the snow. A horse that wasn’t directed by the rider moved in all four directions when the four directions song was happening. That was so neat,” Fairbanks told ICT in a phone call that day.

The riders have been making the 300-plus mile trip from Lower Brule, South Dakota since 2005 to retrace the route their ancestors took decades ago in what is known as the Dakota 38+2 Memorial Ride.

Minnesota Gov. Tim Walz and Lt. Gov. Peggy Flanagan, White Earth Nation, were among the crowd that greeted the riders and runners.

Fairbanks ran in every memorial run since the beginning. During the early pandemic year, the run was postponed. However, that didn’t stop Fairbanks and a few others including his daughter, Andrea. The runners ran the distance themselves, often up to 10 or 12 miles each rather than the more common one mile leg.

Daniel Bearshield, Santee Sioux tribal citizen from Nebraska, ran in his fifth memorial run. He’s a descendent from Sioux City, Iowa.

“My challenge five years ago was that I started running (the memorial run) at age 49 years old,” Bearshield told ICT over the phone. “It was also 27 below zero.”

“Each year after the first year my family have taken five to eight runners to participate,” added Bearshield.

Two Native women were murdered in the past year in Bearshield’s communities. “This year has helped me with the first year of grief,” said Bearshield. “Doing this run brings you back to the center. This is what our family can do to support this run.”

There is talk and resulting action of the horseback ride ending and the run changing leadership. “The old guard is opening this up for the younger generation to continue,” said Bearshield.

Šišókaduta, Sisseton Wahpeton Oyate, is a Dakota language teaching specialist at the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis. He has been at the helm of the memorial run since 2015. He was at the opening fire gathering at Fort Snelling at midnight as Christmas Day turned into the memorial date. He talked about the future of the memorial run as he is retiring from leading it since 2015.

“Everything comes to an end and the younger people need to step up,” he told ICT in a phone call. “We need to pass it to the next generation.”

The late Willard Malebear Sr. died on March 26, 2020. He was a teacher of Lakota language and heritage and he started the commemorative run. As another visionary of the memorial run he shared it with Gonzalez and Fairbanks and others in the mid 1980s. Amos Owen, the late elder at Prairie Island, was the spiritual guide in the early going. The future direction of the memorial run is staying within the families. Willard Malebear, Jr. will be the next leader of the memorial run and elder Ray Owen will help guide the spiritual direction.

Adalyne Jacobo, Crow Creek Sioux tribal citizen, lives in St. Paul, Minnesota. “I ran for the 38+2 Memorial Run for my ancestors and for my aunty Ashley Killsplenty, also a Crow Creek Sioux tribal member, that recently passed away.”

“It was amazing running along the side of the road while running along relatives and having our relatives follow us. It was amazing hearing our relatives cheering us on and for everyone to make it and come together,” added Jacobo.

Lori Walking Eagle, Mdewankanton and Assinibone, said: “It’s important to learn about history. This ride and run keep that history alive.”

“Growing up, I never knew a thing about this event in our country’s history. I have since learned my great, great grandfather Tatecanhpi, was one of those Dakota men tried for ‘war crimes’ merely for being present at the Battle of Wood Lake in 1862. Luckily, he was acquitted after the half-breed interpreter, Antoine Joseph Campbell, testified on his behalf, stating that, ‘This is a good Indian, and he helped guard my teepee at night during the battle.’ Others weren’t so lucky. I’ve read accounts were some of these men were sentenced to hang, merely for firing a shot.”

Walking Eagle continued, “There’s no doubt there’s enough blame to go around. In learning about this history, the government failed miserably in providing the promised goods to these tribes for the land they took. They left them no other option, but to revolt, or starve.

“I can’t even imagine the hardships my ancestors went through, in order for me to be here,” added Walking Eagle.

Casey Ek was with the horse riders from the beginning in early December. He was doing a photographic chronology to the last day. He said after reading a Facebook post about the ride being the last, he reached out to document.

He told ICT in a text message, “I am a photojournalist by trade, so I was drawn to document the ride, knowing it would be impactful for multiple generations.”

“While documenting the ride, it became clear that it was as much about healing from the past as it is about healing from personal traumas for many of the riders and their families, and I was honored and humbled to have been allowed to share in such an important year for the ride,” added Ek.

“The ride this year and the moments I documented, I believe, have the power to open the public’s eyes to historic and modern Native issues, like Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and so many other challenges Natives face. I was also drawn to the ride as a matter of self-exploration. I am Yucatec Maya, so I wanted to see how other Natives did things.”

hannon Bonacci moved to Mankato when she was 11. She was out documenting the riders arriving in Mankato.

Bonacci’s brother became friends with a Native boy. “He introduced us to his culture and his family and helped educate on his history through photos and by inviting us to many powwows where we were allowed to join in as honorary dancers,” Bonacci told ICT.

“I moved away and moved back to Mankato three years ago and have been blessed enough to learn about, educate myself and experience the Dakota 38+2 Memorial Ride the last two years at Reconciliation Park. The amount of peace found each time is amazing, (and) to be able to hear the sounds of the hooves hit the earth from their beloved horses they cherish so much, and to be able to hear their chants, songs and war cries so clearly echo through town gives goosebumps and brings a tear to your eyes each and every time just knowing and hearing the story of the dream two men had to bring forgiveness in their journeys here each year,” added Bonacci.