Robert Bird Horse describes information about North Dakota’s federally recognized tribes from one of his presentations on Jan. 19. (Photo credit/ Adrianna Adame)

Scrolling through his slides, Robert Bird Horse, a social studies teacher at Mandan High School, is always searching for new ways to present lessons for his Native American Cultural Studies course.

This is Bird Horse’s tenth year at Mandan High School, MHS. Previously, he spent four years as an instructional aide at Century High School in Bismarck. When he first came to MHS he started out working as a credit recovery teacher. His current classroom at the Brave Center Academy used to be a computer lab where students would take online classes to make up lost credits in order to graduate. Eventually, Bird Horse transitioned full-time to teaching geography and Native studies to freshmen.

Though the content and curriculum he teaches align with the state standards, Bird Horse puts more effort into the course to make it a more well-rounded learning experience. “I don’t think our standards give Native history and culture enough justification,” said Bird Horse. “We can talk about three or four things when I’d rather talk about 10 or 11 different points. I’ve taken the standards but also expanded it to cover a timeline of a few hundred years.”

Native studies aligns with SB 2304, a law signed by Governor Doug Burgum in 2021, to emphasize the education of the state’s federally-recognized tribes. Currently, Native studies isn’t a requirement, but is offered as an elective. The course does give students credit for their North Dakota studies requirements.

Bird Horse doesn’t use a textbook to teach the four units in his Native studies course. Instead he uses primary sources and online resources.

His curriculum begins in the early 1800s and continues to present-day issues that reservations in the United States are facing. Students first learn about the Lewis and Clark expedition, more specifically about the tribes that helped the explorers and which tribes they’d avoid. Then he goes on to teach about the Great Sioux Wars, as well as Red Cloud and Crazy Horse’s resistance. The next few lessons consist of the Gold Rush, illegal land grabs and treaties. From there his class transitions to learning about assimilation and boarding schools.

Addison McLeish, one of Bird Horse’s former students, said the most memorable topic she learned in Native studies was the assimilation and creation of the Indian boarding schools. “The reality of the topic really widened my perspective and understanding of how different cultures living in America were treated,” McLeish said.

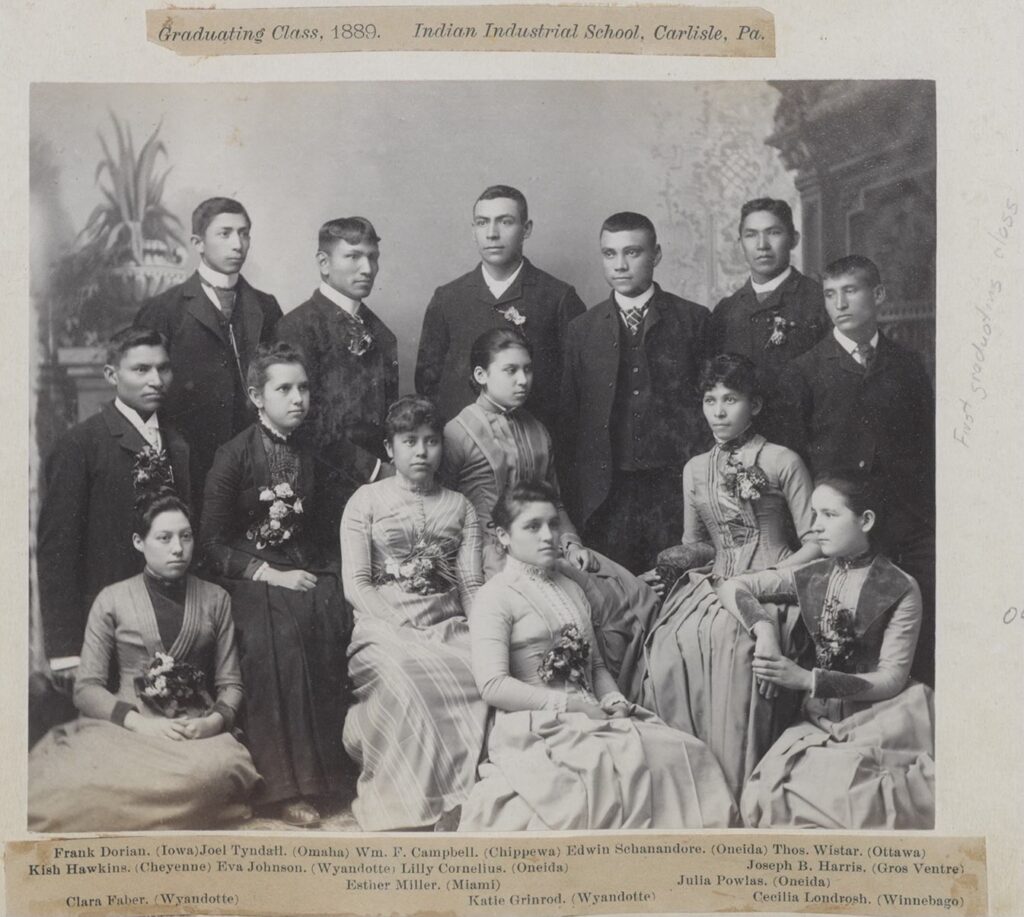

Last semester, Bird Horse’s Native studies class did a study on the boarding schools. Through the National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition and Carlisle Indian School Resource Center, one of his students was able to find information about his great-great grandfather, who had attended Carlisle Indian School in Pennsylvania.

Bird Horse recalled how emotional it felt when that student came up to present his findings to the class. “It was really cool to read his student ID card, because of how the teachers described his great-great grandpa –– is exactly how that kid is today,” said Bird Horse. “He’s in band, he’s in sports and he’s a very good student.”

School was never hard for Bird Horse, but he wished there were more American Indian instructors to connect with and learn from as he continued his education. “I always had good teachers and they always made connections with us,” said Bird Horse. “But one thing I was always missing as I went throughout school was not having a Native teacher. Part of my motivation for going into teaching was to be that person for [Native] students.”

The instructor, an enrolled citizen of the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe, lived on the reservation in Fort Yates for three or four years before he and his parents moved to Bismarck. Bird Horse spent his K-12 years in the area until he graduated from Bismarck High School. Though he had a positive experience in Bismarck, he said he wishes he could have grown up on the reservation to incorporate the culture and language in his day-to-day life. “It kinda felt like a disconnect to me, growing up in a non-Native society,” Bird Horse said.

Students often come back to visit after the semester is over and tell Bird Horse they wish Native studies was a year-long class rather than a single semester. Karley Gange, an eleventh grader at MHS, took Bird Horse’s course two years ago. The teen chose to take Native studies because she wanted to learn about more about the Indigenous history and perspectives of those from this region.

“If I would have never taken Native studies, there’d be so much information that as someone who is not Native, never learns about,” said Gange. “Our basic history books fail to teach many key events, like the Battle of Little Bighorn and the execution of the 38 Sioux, which makes them my favorite topics we learned about.”

Bird Horse completes the 18-week course by teaching Native rights, and the events of the Dakota Access Pipeline, a 1,168-mile system that would carry up to 750,000 barrels per day of U.S. light sweet crude oil from the Bakken and Three Forks production region of North Dakota to Patoka, Illinois. While Bird Horse knows some of what he teaches can be controversial, he focuses on sticking to the facts. “I think students are pretty receptive, just because I don’t take a stand [on issues],” said Bird Horse. “I just try to break apart all those barriers and say these are the historical facts I’m going to teach you guys and this is the side we’re going to be hearing from.”

While it’s been smooth sailing for the most part, it’s sometimes hard for Bird Horse to teach from a United States and Indigenous perspective. But the instructor tries his best to find a middle ground. “Our country had goals, but our people had goals and objectives as well,” said Bird Horse. “Seeing both sides of the story is probably the biggest challenge I have. We can learn from history, even though there is nothing we can do about the past –– we can adapt to new ways.”

After students finish the Indian Boarding Schools unit, they are going to visit the former site of the Bismarck Indian Boarding School in April. Staff will give students a tour and show them where the dorms and classrooms were. Despite taking years to arrange, Bird Horse said he is glad to finally give students a chance to connect and interact in first person with a topic they are learning about.

In the future, Bird Horse wants to solely focus on teaching Native studies. “I easily have enough content and information to make it a year-long class, which is one of my goals, but right now I’m satisfied with it being a semester class,” Bird Horse said.

Dickinson College. (n.d.). Student records. Student Records | Carlisle Indian School Digital Resource Center. https://carlisleindian.dickinson.edu/student_records

K-12 Education Content Standards. North Dakota Department of Public Instruction. (n.d.-a). https://www.nd.gov/dpi/districtsschools/k-12-education-content-standards

Leading the Movement For Truth, Justice, and Healing. The National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition. (n.d.). https://boardingschoolhealing.org/

State Historical Society of North Dakota. (n.d.). SB 2304. North Dakota Studies. https://www.ndstudies.gov/native