Ledger Art: An homage to the past, creating art for the present and future

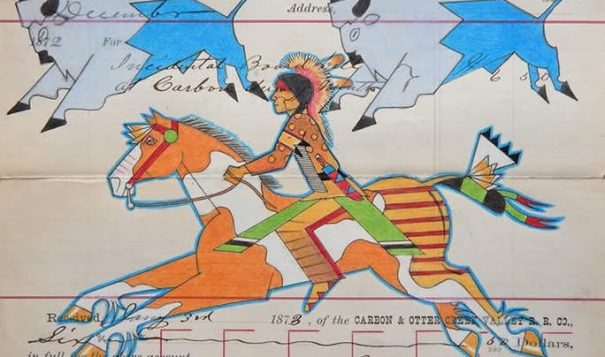

Ledger art by Monte Yellow Bird Sr., an Arikara/Hidatsa ledger artist from North Dakota

Ledger art by Monte Yellow Bird Sr., an Arikara/Hidatsa ledger artist from North Dakota

Ledger art is a form of art unique to Native American artists. Ledger art started during the Indian Wars in the mid-to-late 1800’s when many Natives were put into prison camps. The prison guards would give the Native prisoners paper, pencils and crayons so the Natives would have something to do.

Some of the paper given to Native prisoners was from ledger books. In the confines of a cell, Native artisans would draw what was on their mind – memories of a battle, people or an event. Traditionally, the art that would inspire ledger art was painted on buffalo hides, shields, tipis, shirts, leggings, or robes.

But after the buffalo herds were wiped out to near extinction and Native people were rounded up by the U.S. military, the artform made a dramatic change and was transferred to paper. The use of traditional paints and bone and sticks for brushes also vanished.

Ledger art was mostly created from about 1860-1920. After fading out it made a comeback in the 1960s and 70s and is flourishing today.

Omaha ledger artist Travis Blackbird says the paper is the essence of the art-form.

He says the paper is what gives today’s ledger art its authenticity. “The paper will give a time and a place for history’s sake,” he said. “Say a map from around the time of the Sand Creek Massacre (in Colorado). There are certain collectors and they’ll see it’s authentic.”

“You can find the paper on e-bay or go to an antique store and try to find that old paper but it has to have a date, a place and name. A lot of paper I deal with will come with stamps, or it will come with a date on it or a watermark,” says Blackbird, who grew up in Sioux City, Iowa and is also Oglala Lakota.

Monte Yellow Bird Sr., an Arikara/Hidatsa ledger artist from North Dakota says that his artform is important and that he is “a historian as well as an artist.”

“I think it’s our responsibility to write and tell the story about that particular time. Ledger art is not just a visual artistic presentation. It’s reflective of a transitional time for Native people. History is a big part of us and ledger art really fits. It gives the idea that we’re a very resilient people.”

Though the art genre had largely depicted men at its inception, Native women have been creating ledger art for the past three generations. Linda Haukass, a Sicangu Lakota from the Rosebud Reservation in South Dakota, who received her Master’s Degree from the University of Nebraska-Lincoln and now lives in Sarasota, Florida., is known as the grandmother of women’s ledger art.

“I’ve always painted and drawn for as long as I can remember but what really lit the fire in my belly was my grandmother, who showed me a picture of my grandfather’s (ledger art) and it was pictographic. I was really quite young, about 11 or so. That was my introduction and from then on it just developed,” said Haukass.

“I was doing what the traditional pictography was doing, which was male-oriented with battles and deeds,” Haukass told ICT. “It didn’t sit well with me doing the testosterone-based drawings. I started to create drawings which involved women and women’s daily lives and their ceremonial lives. From there I evolved to doing social commentary about the relationship between Indian artists and art patrons. Those were the ones that garnered critical acclaim at the Indian markets and museums.”

Haukass says she embraces tradition, but also enjoys a sense of freedom in her artistic portrayals.

“Whatever strikes my interest, whether it is blood quantum or appropriation of tribal art forms by non-Indians, is what I draw about. Drawing about complex issues is much easier for me than to speak about or write about them,” said Haukass.

Monte Yellow Bird Sr., who also goes by Black Pinto Horse, says he never undervalues the impact of his art-form.

“There’s a power that is attached to our work and actions. The ledgers were a variation of different documents. Some of them were military documents and some of them were general store papers. They became the spoils of war when (Natives) would attack forts or towns and they would steal this paper. It became a coup, so to speak”,

“Another idea, that is probably more popular to mainstream historians, begins with the Fort Marion prison back in St. Augustine. For the most part, the general public really sees that as where ledger art came from. But there are other areas how we got paper. It’s getting to be a real popular art. As a historian and a descendant of ledger artists, it’s part of my responsibility to tell the stories and not just the pretty pictures.”

Blackbird, who did his first artist showcase last weekend in Albuquerque, says “I do ledger art for the love of creating something I can do.”

“If it can reach someone and do something for them it’s all the better. For me it’s a history lesson too because I have to learn a place, a time, why (an event happened) – so I’m still learning myself.”

Our goal is to help our community stay informed. The Buffalo's Fire Newsletter is published at 12 p.m. CST every Wednesday. Our digital news site is published by the Indigenous Media Freedom Alliance, a Native-led, Native-woman founded nonprofit media organization based in Bismarck, N.D. We can be reached at 701-301-1296.

By submitting this form, you are consenting to receive marketing emails from: . You can revoke your consent to receive emails at any time by using the SafeUnsubscribe® link, found at the bottom of every email. Emails are serviced by Constant Contact

Jodi Rave Spotted Bear

Jodi Rave Spotted Bear is the founder and director of the Indigenous Media Freedom Alliance, a 501-C-3 nonprofit organization with offices in Bismarck, N.D. and the Fort Berthold Reservation. Jodi spent 15 years reporting for the mainstream press. She's been awarded prestigious Nieman and John S. Knight journalism fellowships at Harvard and Stanford, respectively. She also an MIT Knight Science Journalism Project fellow. Her writing is featured in "The Authentic Voice: The Best Reporting on Race and Ethnicity," published by Columbia University Press. Jodi currently serves as a Society of Professional Journalists at-large board member, an SPJ Foundation board member, and she chairs the SPJ Freedom of Information Committee. Jodi has won top journalism awards from mainstream and Native press organizations. She earned her journalism degree from the University of Colorado at Boulder.