Inspired by her grandparents, Tonah Fishinghawk-Chavez proves that caring for the community is an action, not just a word

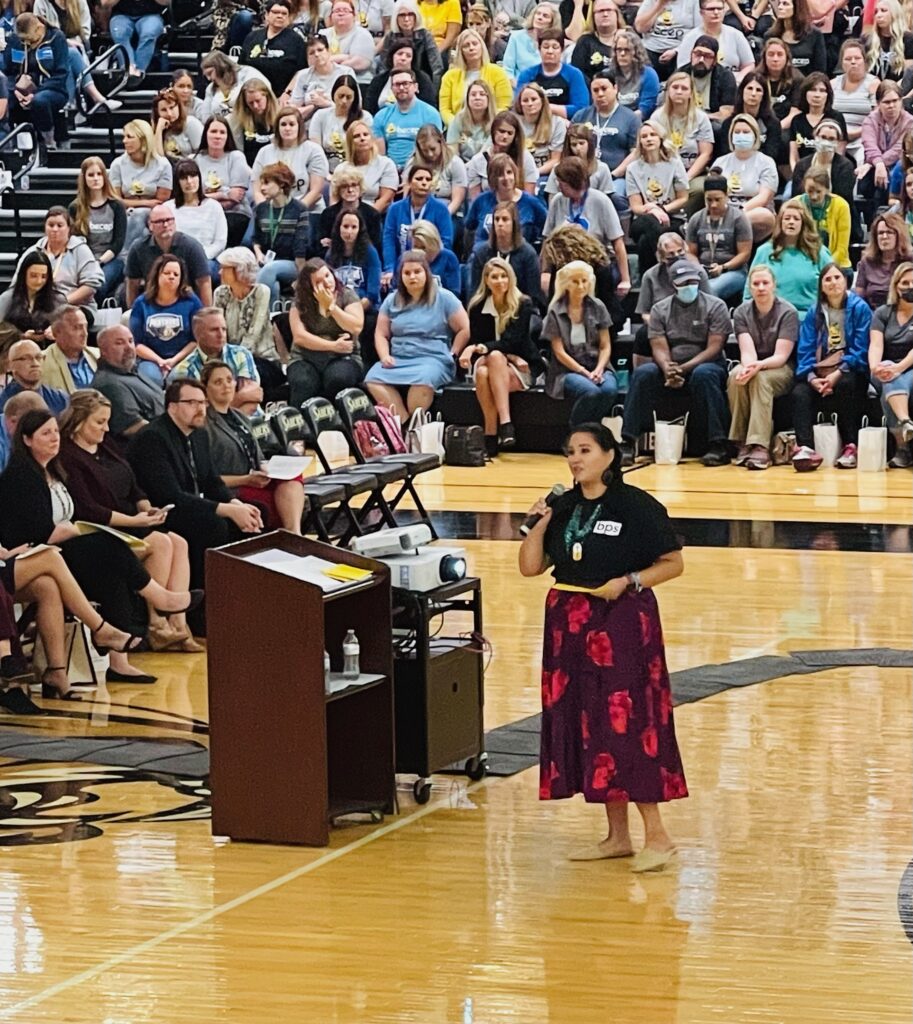

Sashay Schettler, Bismarck Public Schools Indigenous education director, delivers a land acknowledgement in 2021-22 to fellow school district staff members at Legacy High School in Bismarck, N.D. Schettler is a citizen of the Mandan, Hidatsa and Arikara Nation. Photo Credit/Bismarck Public Schools

My teenage daughter recently told me about another student who stood in front of a land acknowledgment sign. It was posted in a classroom at Legacy High School in Bismarck, N.D. The student read the land statement aloud, unsure of how to say “Indigenous.”

My daughter, who is Mandan, Hidatsa, and Lakota, pronounced the word. The girl said, “whatever,” and then questioned the need for such an acknowledgment in the first place. She said Native people should “just get over it.”

It’s not up to my daughter to educate fellow students about the meaning of language packed into a land acknowledgment. This task should fall to North Dakota’s K-12 educators. I know, all too well, what it feels like to be the sole person who has to fill in the Native knowledge gaps of others.

As a journalist, I’ve done scores of presentations and written abundantly on Indigenous issues, all in the spirit of sharing information about Indigenous peoples.

“At one point in time, we were the majority population. What happened?”

Jodi Rave Spotted Bear – Mandan, Hidatsa, and Lakota

First, Bismarck Public School educators deserve kudos for posting land acknowledgments that recognize the traditional homelands of the Nueta, Hidatsa, Sahnish, Anishinaabe, and the Oceti Sakowin nations located in North Dakota. The people of these tribes remain important to the contemporary culture of the United States.

Some people, however – Native and non-Native –question whether land acknowledgments serve a purpose. In 2018, I was in Alberta, Canada at the Banff Centre. It was the first time I heard a land acknowledgment, which is a formal statement that recognizes Indigenous peoples’ connection to land or territory typically now occupied by people who took possession of it.

I’ve yet to hear a land acknowledgment explain why Indigenous peoples no longer occupy the land. The formal statements, either posted or read aloud at an event, raises questions: Where are the Indigenous people now who once inhabited this space? What are their contemporary and historical stories? How did they lose possession of their land?

Teaching opportunities abound for educators to discuss land dispossession. March commemorates the 200th anniversary of Johnson v. McIntosh, a Supreme Court case that declared the U.S. government had a legal claim to control Indigenous lands. It stripped Native people of title to their ancestral lands and granted them only a “right of occupancy.”

Arizona State University recently hosted a daylong webinar on Johnson v. McIntosh, allowing the discussion to unravel the “international law of colonialism” in recognition of Indigenous land loss around the world.

North Dakota has a rich American Indian cultural history. And rich contemporary discussions await considering Native people represent the largest minority population in the state, about 6 percent. At one point in time, we were the majority population. What happened?

I appreciate living in the Bismarck-Mandan area where historical earth lodge villages sites of the Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara nation abound — Double Ditch, Menoken, Huff, On A Slant, just to name a few of the protected village sites mostly found near the Missouri River.

It’s good to see Bismarck Public Schools display land acknowledgments. It would help if K-12 educators spent more time teaching students about them. As formal land statements grow in popularity across the United States, the declarations rightfully recognize our historical connections to the land. It’s not something we will ever “get over.”

“We can all do our part and plan for a better future by working together.”

Jodi Rave Spotted Bear – Mandan, Hidatsa, and Lakota

We would all do well to acknowledge Indigenous peoples as the original caretakers and stewards of the land. In 2019, as a guest presenter of the Center for Arts Design and Social Research, I interacted with Mayan language teachers and Maya artists on several art projects while in Yucatan, Mexico.

At a public art performance in Merida, Mexico, I suggested our group do a land acknowledgment for the Maya. I was honored when asked to be the person who read the statement. Teaching opportunities exist every day for educators to explore Indigenous cultures.

The Native Land Digital website shows Indigenous lands throughout the world. The interactive site “creates spaces where non-Indigenous people can be invited and challenged to learn more about the lands they inhabit, the history of those lands, and how to actively be part of a better future going forward together.”

We can all do our part and plan for a better future by working together.

Jodi Rave Spotted Bear (Mandan, Hidatsa and Arikara Nation)

Founder & Editor in Chief

Location: Twin Buttes, North Dakota

Spoken Languages: English

Topic Expertise: Federal trust relationship with American Indians; Indigenous issues ranging from spirituality and environment to education and land rights

See the journalist page1. ILP Webinar: Unraveling the International Law of Colonialism: The 200th Anniversary of Johnson v M'Intosh--March 10 2023 https://vimeo.com/810597464/87f452d487

2. Native Land Digital, https://native-land.ca/

© Buffalo's Fire. All rights reserved.

This article is not included in our Story Share & Care selection.The content may only be reproduced with permission from the Indigenous Media Freedom Alliance. Please see our content sharing guidelines.

Native organizations and food banks are stepping in to compensate

Dramatic play reveals power of Indigenous stories and community

Thousands peacefully protest

More than 3,000 participants attend Minneapolis event

Appeals court to rule soon in a case first filed last year