Indigenous youth leaders gather to talk MMIP, climate

More than 2,400 Indigenous youth leaders from hundreds of Indigenous nations come together at the 2023 UNITY conference to talk about issues impacting their communities.

Pauly Denetclaw

ICT

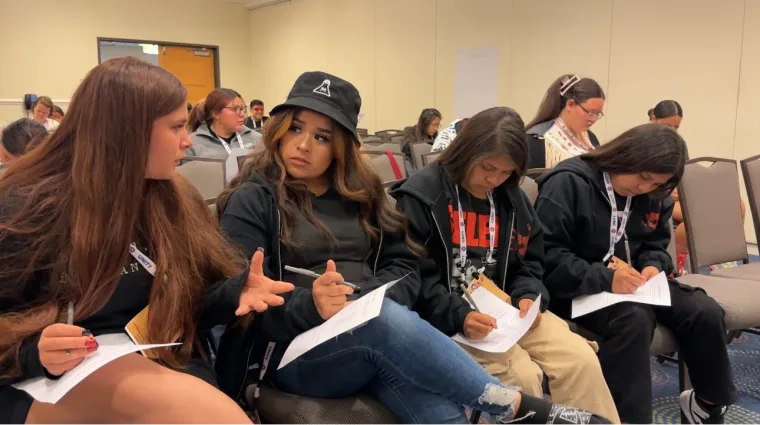

Kaitlin Cachora, 14, from the Tohono O’odham Nation in southern Arizona was one of over 2,400 youth leaders to attend 2023 UNITY Conference in Washington, D.C. (Pauly Denetclaw, ICT)

Helen John, 17, was sitting quietly with two of her friends in a dimly lit conference room. The panel was about Thacker Pass and the movement to stop lithium mining in the area. During nearly the entire panel the group of students sat silently listening to how cultural sites and eagles would be deeply impacted by this development.

Near the end John, Tlingit, shared with the youth trying to protect Thacker Pass how another industry is similarly impacting her community in Yakutat, Alaska. Every winter and summer, she goes back to her village to forage, fish and hunt.

Unfortunately, this has been impacted by the logging company Yak Timber that is clear-cutting the forest in the area.

“At the moment, it’s very hard for us to go out hunting because almost all our trees are gone,” she told ICT. “Our corporations didn’t make any money off of the trees that they had logged. So, right now we are bankrupt and all of our land is being taken by the banks.”

She was one of over 2,400 youth leaders from across the country who came to the 2023 National UNITY Conference. UNITY is youth-led and focuses on those 14 to 24.

The young people who attend this gathering are part of one of the 320 UNITY affiliated youth councils that operate in 36 states. The conference is a chance for young people to talk about and connect with each other about issues that are important to them.

“It really hurts my heart and it’s very sad. When I went back to Yakutat right after the pandemic, it was the most heartbreaking thing to see because you drive out and I was crying for the 30 minute ride out to our village from the airport,” John said. “It was really hard because you would see all of our birds, and sometimes you see bears because we’re in a remote location. Now there’s barely any of that and they’re all gone. It’s really hard.”

Kaitlin Cachora, 14, from the Tohono O’odham Nation in southern Arizona has had two family members who were murdered. This is why missing and murdered Indigenous people is an important issue to her.

“My auntie, the late Sarah Cachora, she was murdered by her boyfriend along with her son and at first it was MMIW for her. Until I found out that her eight-year-old son had been murdered too. Then I followed with MMIP. That’s the biggest concern that I have,” Cachora said. “I felt like they should have more workshops or something like this. Letting them know that MMIP is something and happens all over the country and just be more aware.”

Another important topic for young people at UNITY was global climate change and the impact on water resources.

Incoming Arizona State University freshman, Jovi Williams, White Mountain Apache, hopes to do more work around water preservation as an Earth Ambassador for UNITY.

“We need to protect our water. Water is the major natural blessing given to us by Mother Earth. Without water there cannot be life,” Williams said. “As the White Mountain Apache Tribe we offer more water to the Phoenix metropolitan area. The local rivers, streams, springs, they all come from the White Mountain Apache area, from Mount Baldy and flows all the way down to Salt River.”

His message to members of Congress, state elected leaders and tribal governments was simple: Stop letting money talk.

“Money can control so much,” he said. “It can change the ideology of so many people.”

Climate change is impacting the salmon population in Alaska, the Dakota Access Pipeline is creating pollution, even in Washington, D.C. the smoke from wildfires in Canada are affecting air quality, Williams said.

“We’re united and strong and will confront all these issues, especially the environmental work,” he said. “One thing I want to leave off (on) is continue the work in our environmental advocacy. Without our Mother Earth we cannot have a bright future. Continue to tie in your cultural knowledge in ways to protect Mother Earth.”

Aleisha Velasquez, 19, is also from White Mountain Apache. The issue she is most concerned about in her community is mental health. She graduated from Alchesay High School in 2021 and she knows at least six of her former classmates have committed suicide.

“I grew up going to wakes and going to funerals more than I’ve gone to weddings and graduations,” she said. “When you’re growing up on the reservation, when you’re born and raised, you’re so used to it but when you go to college, it’s not like that for white students and for your white peers.”

Velasquez wants more culturally competent mental health resources allocated to her rural community in southeast Arizona.

Kainoa Azama, 21, is Kānaka Maoli and is currently attending the University of Hawai’i at Mānoa where he is studying political science and Hawaiian studies. His biggest concern is the sovereignty of the Kānaka Maoli.

“One of the bigger things I’m concerned about is this movement towards federal recognition,” Azama said. “From an illegal overthrow to an illegal occupation, there should be a legal solution following those layers of illegalities. So I can’t help but wonder and question moving in a direction that’s clearly not served a lot of people in a really good way.”

Growing up in Hawaii another major concern is obviously climate change.

“If you cannot heal an island, how are you going to heal the planet?,” he said. “The best way to heal Hawaii and to undo the changes that have happened with climate change and these behavioral outcomes, is to maybe just leave it alone and let the people who are from the place start to influence.”

Azama hopes that unity will prevail as the issues of climate change become more important with every passing year.

“He wa’a he moku, he moku he wa’a,” Azama said, which he said translates to: “‘An island is a canoe and a canoe is an island,’ and the wisdom that our elders said is that if you want to make the distance you need to work together. If you want to go fast, go alone. But I think as islanders on this island Earth, that moves through that sea of space and time, we need to start working together to make that distance.”