'Native teachings continue to live on' in project-based school born out of #NoDAPL movement

Iloradanon Efimoff, a social psychologist professor at Toronto Metropolitan University, said her advice to researchers and the audience is to do something that’ll make a difference for their community during her March 13 presentation. Photo credit/ Adrianna Adame

“Show me the data,” said Stephanie Fryberg, organizer of a new conference dedicated to promoting what she calls “data sovereignty” in a society where “data has been systemically weaponized against Indigenous Peoples.”

Amidst a startling backdrop where 87% of state history standards in the U.S. fail to mention American Indian history post-1900, the inaugural Indigenous Truths Rising: Social Action & Equity Conference, or RISE Conference, for short, challenged narratives and fostered vital conversations on education reform. The RISE Conference is an initiative of the RISE Center, based at Northwestern University.

American Indian researchers and educators discussed the urgent need for data “by Indigenous People, for Indigenous People.” They decried the damage caused by Western research methods through erasure, racism and exploitation of Native people.

Around 150 attendees participated in the three-day conference from March 11-13 at the Tulalip Resort and Casino in Tulalip, Wash. The first evening consisted of a welcome reception, along with another two days of full sessions. Three tracks focused on education, invisibility and Missing and Murdered Indigenous People/Violence. An additional session, “Democracy is Indigenous,” included a training workshop by the Center for Native American Youth to encourage data decolonization.

According to Fryberg’s website, the conference aimed to help attendees “Walk away with resources, talking points, and more in dialogue directly with the lead scientists who can support your work in law and policy, education, tribal sovereignty, and social justice.”

“We have an overwhelming percentage of non-Native people who only conceive of Indigenous peoples in the distant past.”

Sarah Shear- associate professor at the University of Washington-Bothell’s School of Educational Studies

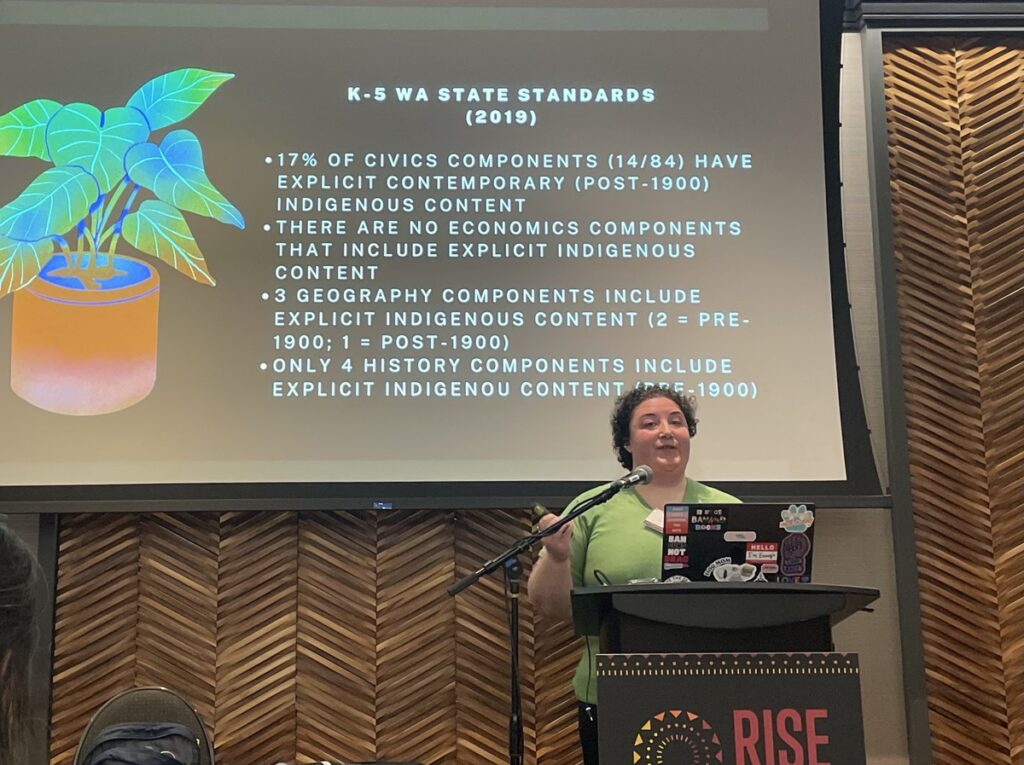

Sarah Shear, an associate professor at the University of Washington-Bothell’s School of Educational Studies and speaker at the conference, has researched each one of the 50 states’ curriculum standards. Shear held the session “For Future Generations: A Call for Anti-Colonial Commitments in Social Studies Curriculum.” Her presentation showcased her data from three national curriculum studies on the inclusions and erasures of Indigenous peoples in social studies education.

Before she entered academia, Shear worked as a K-12 government teacher. In that role, students have asked her some surprising questions, including whether American Indians ever lived in Missouri. Based on that experience, Shear realized the importance of featuring contemporary American Indian history and issues in schools.

“We have an overwhelming percentage of non-Native people who only conceive of Indigenous peoples in the distant past,” Shear said.

According to a study Shear conducted, 87% of K-12 U.S. history standards explicitly include Indigenous content only in a pre-1900 context. At the time of her research’s publication, 40% of U.S. civics and government standards stated that Indigenous nationhood is situated in a pre-1900 context.

Eventually, this led Shear to ask bigger questions about the curriculum, which brought the former government teacher to her doctoral studies at the University of Missouri. “Well if the curriculum guide is not going to be helping any of us learn about the governments who we are neighbors with, I’m not too sure what we are doing here and I’m not sure why I’m a government teacher.”

Iloradanon Efimoff, an assistant social psychology professor at Toronto Metropolitan University, held an education-track session on Reducing Anti-Indigenous Racism Through Education. The presentation consisted of five different studies over four years as a part of her dissertation on racism towards Indigenous peoples.

The first was an interview study where Efimoff talked to Indigenous students about their experiences with racism, so she could create an intervention to address the issue. Then Efimoff surveyed 400 Indigenous students to continue learning about how modern and systemic racism affected them. In another study, she asked non-Indigenous people about what they wanted to learn about in terms of Native culture. The last two studies included experiments that taught participants about interpersonal racism, which focused on the empathy and feelings non-Natives felt about Indigenous people after they learned about Canada’s residential schools.

Efimoff, a citizen of the Haida Nation in Canada, knew this would be a tough topic to immerse herself in. “I think the most difficult part was constantly being face-to-face with these racist realities,” said Efimoff. “And you experience them as you move through the world. Sometimes, I think it just weighs down on you emotionally, psychologically and spiritually. But I think that I managed because I had an amazing circle of support.”

Shear blames the lack of a well-rounded social studies education for contributing to misinformation about the history of Indigenous Peoples. “Social studies education nationwide is failing to provide teachers the training and students the ability to not only learn accurately but to learn from an anti-colonial frame and Indigenous educators,” Shear said.

A recurring theme during the sessions was the perception that all of the problems in education are interconnected.

According to Efimoff, the main takeaway is the importance of teaching the ways in which systemic racism works, and the fact that it’s a recurring problem. “We have hundreds of years of settler colonialism that have created these structures that have caused all of this harm,” said Efimoff. “So we need to be consistently and intentionally teaching people the truth so that they can move themselves away from those ideas — so that we can all move forward together.”

While eliminating the effects of systemic racism will require generations to complete, there are steps people can take along the way to address this ongoing challenge. It matters who’s in the room, said Shear, and Indigenous educators need to be heard.

“A lot of people who end up on state writing committees for these state standards have never set foot in a classroom before,” Shear said. There is a need for Indigenous and non-Indigenous educators to curate curriculum, she said, rather than officials without the background experience.

Efimoff’s advice to researchers and the audience is to do something that will make a difference. “For the researchers out there, it’s really important that the work we do has applied practical outcomes,” said Efimoff. “But our research can’t just contribute to theory, it needs to contribute to changing the world — to making it a better, safer and cleaner place for everybody involved.”

Adrianna Adame

Former Indigenous Democracy Reporter

Location: Bismarck, North Dakota

See the journalist pageEfimoff, I. H. & Starzyk, K.B. (2023). The impact of education about historical and current injustices, individual racism, and systematic racism on anti-Indigenous prejudice. European Journal of Social Psychology, 53, 1542-1562. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.2987

Indigenous Truths Rising: Social Action & Equity Conference. RISE. (n.d.-b). https://www.riseresearchconference.org/

Shear, S.B. (in process). Settler Social Studies: Tracing Supremacist Ideology Across K-12 State Standards. Routledge.

© Buffalo's Fire. All rights reserved.

This article is not included in our Story Share & Care selection.The content may only be reproduced with permission from the Indigenous Media Freedom Alliance. Please see our content sharing guidelines.

Curtis Rogers sets his sights on law school

Students use space to relax and connect to Native culture

New law requires schools to teach Native American history

Terrence and Patricia Leier are ‘giving back for the sacrifice that the Natives made’

Bush Fellow eager to draw more young adults to college