This article was produced for ProPublica’s Local Reporting Network in partnership with Honolulu Civil Beat

ProPublica

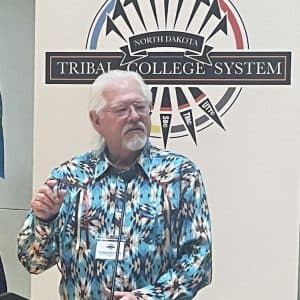

During the celebration on Dec. 5, Sheridan McNeil, director of Tribal Partnerships for the North Dakota Established Program to Stimulate Competitive Research, and Heidi Grunwald, associate vice president for research and faculty development at North Dakota State University, presented a blanket to the board of directors of the Tribal College System in North Dakota in recognition of their 30 years of dedication and service. Photo credit Adrianna Adame

Indigenous educators gathered to celebrate the 30th anniversary of the North Dakota Tribal College System at the North Dakota Heritage Center on Thursday.

“This event is very significant in that we were the first state coalition of Tribal colleges,” said Tracey Bauer, the Executive Director of the NDTCS. “And so that really speaks to our predecessors and their visionary thoughts, that they actually had the foresight to know that this was needed and that this was an association that was going to be able to stand the test of time.”

What began as Tribal-founded colleges operating on shoestring budgets has grown into a powerful educational and economic force. The five Tribal colleges in North Dakota now generate $169.5 million in annual economic impact and support more than 2,000 jobs statewide. Nearly three-quarters of graduates either work within their reservations or remain in-state, contributing $104.4 million in increased earnings to North Dakota’s economy.

Veterans of Foreign Wars Post #9061 and the Mandaree Singers opened the event with a song and the posting of the colors. Leander “Russ” McDonald, president of United Tribes Technical College, offered the invocation and a prayer, and Twyla Baker, president of Nueta Hidatsa Sahnish College, delivered the opening remarks. Prairie Rose Seminole, an advocate and citizen of the Three Affiliated Tribes, served as emcee throughout the event.

The celebration featured three main parts. The first, “Honoring Our Past,” featured Gerald “Carty” Monette, a founding board member of the NDTCS and president of Turtle Mountain College from 1975 to 2005. He shared the history of Tribal colleges in the state and nationwide.

Monette emphasized the importance of partnership and collaboration. He noted that the Tribal College Movement of the 1970s played a key role in shaping the positive impact these institutions continue to have on both reservation and off-reservation communities today.

The American Indian Higher Education Consortium was established in 1973 by the first six tribally chartered colleges in the United States, including: Navajo Community College, now known as Diné College; Ogalala Sioux Community College; Standing Rock Community College, now known as Sitting Bull College; Turtle Mountain Community College, now known as Turtle Mountain College; Fort Berthold Community College, now known as Nueta Hidatsa Sahnish College; and Sinte Gleska College.

Today, the AIHEC represents 37 institutions nationwide. North Dakota has five Tribal colleges, the second-largest number in the country, following Montana, which has seven.

“I think it’s safe to say that the creation of the American Indian Higher Education Consortium is a result of participation and the influence of the North Dakota Tribal Colleges,” Monette said. “And that’s important to know.”

In 1973, Tribal colleges were not yet accredited. Monette and others pushed for their accreditation to enable these institutions to access previously ineligible funding. At the time, available funding was limited, and additional financial support was needed to better serve staff and students.

“The colleges were created by the tribal governments,” he said. “They had nothing, except for that money that was being controlled by the mainstream institutions to hire a few staff, mostly faculty people, to teach some classes on the reservation. No facilities. No money for staff. No money for resources. No money to buy books. No money to hire people. No money at all.”

The game changer for Tribal colleges was the Tribally Controlled Colleges and Universities Assistance Act of 1978, signed by President Jimmy Carter. The bill authorizes federal assistance to institutions of higher education that are formally controlled or have been formally sanctioned or chartered by the governing body of an Indian Tribe or Tribes.

“The money started to flow,” Monette said. “The one thing about becoming eligible for funding from the Tribally Controlled Colleges and Universities Assistance Act is that we had a financial base, and we were able to seek and get accreditation. When accreditation opened up, we received money for every enrolled Indian student at our institution.”

Since then, Tribal colleges have been able to thrive. As a part of their continuing growth, these institutions have been implementing more collaboration locally and nationally.

The second part, “Celebrating Our Present: The Importance of Meaningful Partnerships,” featured Colleen Fitzgerald, vice president of the Office of Research and Creative Activity at North Dakota State University. She discussed how building connections can open doors to new opportunities.

Fitzgerald previously ran a Documenting Endangered Languages program through the National Science Foundation. Through her work there, she met Tribal leaders and educators, such as Monette, McDonald and Baker. They came up with “an idea of bringing worlds together and seeing how we could cross-pollinate if we built those relationships,” she said.

As the program officer, Fitzgerald was also able to fund a language revitalization project at Sitting Bull College that focused on what the community wanted. She encourages local and national organizations to work together with Indigenous communities and listen to their needs.

The final part, “Envisioning the Future: Strategic Plan Overview,” featured Twyla Baker, who is also the current chair of the North Dakota Tribal College System Board of Directors. She discussed five strategic goals recently developed for the system: ensuring rigorous curricula and high-impact educational practices; fostering a culture of institutional effectiveness and accountability; improving enrollment, retention and completion rates; cultivating partnerships with Tribal communities; and integrating culture into college programming.

“We have several Tribal nations within our boundaries,” Baker said. “It’s crucially important that Tribal colleges are seated both on Tribal land and in our urban centers where many of our people are also residing to make sure that we’re making those higher education opportunities available to the people who might not necessarily even attend college if it weren’t for the Tribal colleges.”

In the 2022-2023 academic year, the system had 2,607 credit students, 314 non-credit students, and 657 employees.

“It’s an exercise in sovereignty,” Baker said. “It’s a really great way to build our social mobility and economic development and to provide a grounding in culture and place and identity for our young people prior to heading out into the workplace.”

Based on this study, Bauer said the NDTCS will launch an economic campaign in 2025. The report will help guide their efforts in achieving the system’s next economic goals, aligned with their five-part strategic plan.

“I just think that it’s really great that we’ve been able to sustain this partnership throughout the years,” Bauer said. “And so it’s just really a celebration of that and where we can go and where we plan to go.”

The NDTCS board of directors is looking forward to the next few years ahead. Before the celebration ended, they thanked educators and students for their dedication to higher education.

“It’s a good time to mark a milestone for us and come back together to remember where we were from, get regrounded and let everybody know where we’re headed for the future,” Baker said.

Adrianna Adame

Former Indigenous Democracy Reporter

Location: Bismarck, North Dakota

See the journalist page© Buffalo's Fire. All rights reserved.

This article is not included in our Story Share & Care selection.The content may only be reproduced with permission from the Indigenous Media Freedom Alliance. Please see our content sharing guidelines.

This article was produced for ProPublica’s Local Reporting Network in partnership with Honolulu Civil Beat

ProPublica

Inspired by her grandparents, Tonah Fishinghawk-Chavez proves that caring for the community is an action, not just a word

Police and family looking for Angel Mendez and Zayne LaFountain

The billboard project is expanding to Oregon

The film tells the story of white buffalo calves on the Turtle Mountain Reservation

Two years ago, Angela Buckley-Tocheck turned to Native Inc. for assistance with housing and to escape traffickers. Now she works there