Dramatic play reveals power of Indigenous stories and community

Gaps form as youth mental health challenges rise

Solving challenges takes system-wide approaches

Michael Standaert

North Dakota News Cooperative

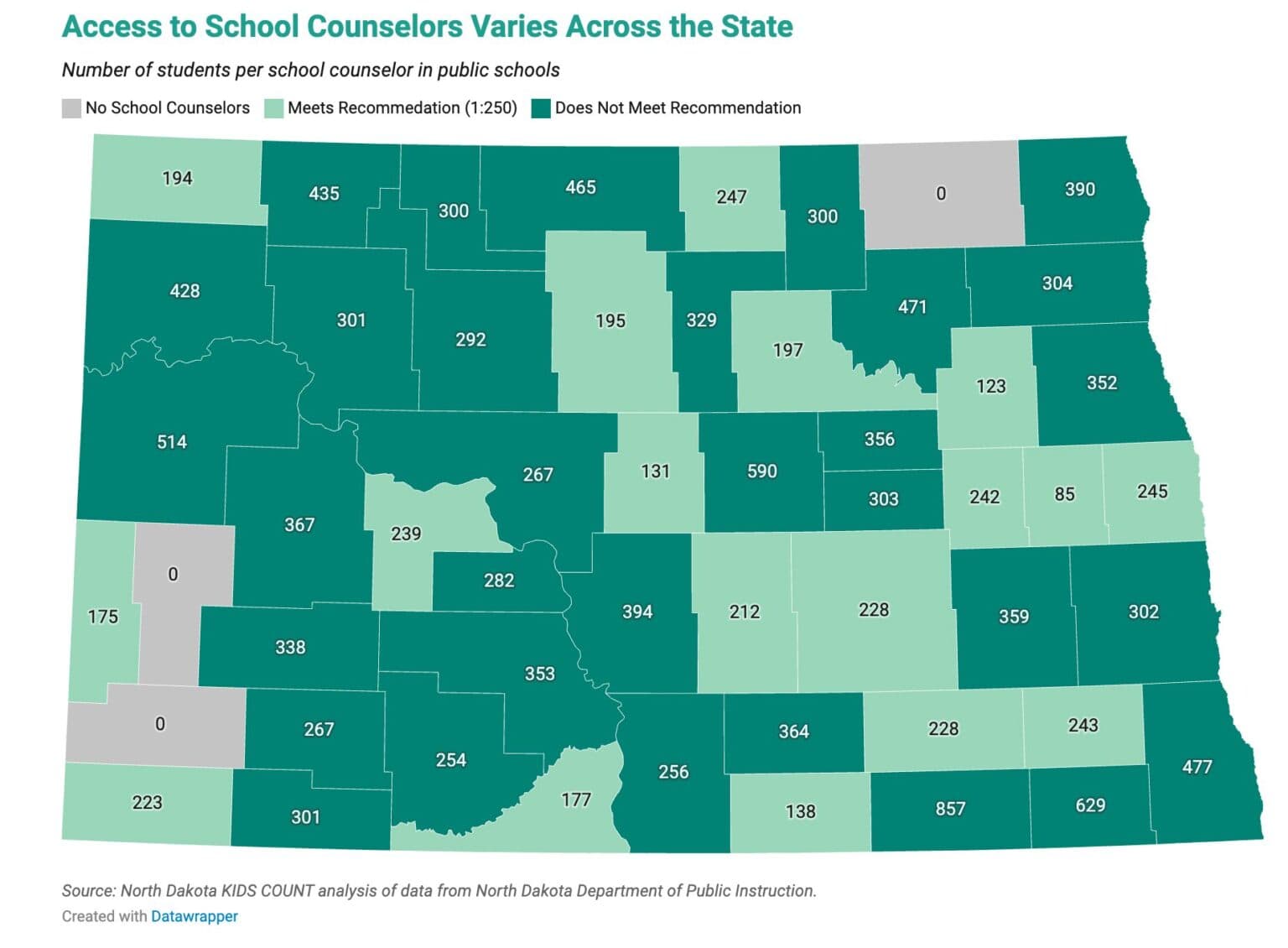

This graphic shows the number of school counselors there are to students across North Dakota counties using 2023 data. A check with Cavalier County found that they do now have a counselor in the school system there. A total of 35 counties do not meet the American School Counselor Association recommended ratio of one counselor to 250 students.

With over two decades as a counselor in Langdon area schools in rural Cavalier County and as a clinical counselor with Catholic Charities, Barbara Boesl has seen shifts in youth mental health.

Anxiety has supplanted depression as a primary diagnosis for those struggling, both on the youth and adult side, she believes.

“My belief is that (increase in anxiety) is connected to the lack of real connections,” Boesl said. “In the smartphones, that is a connectedness that’s not really connected. It’s so easy to go into distraction, but we crave real, true connection.”

That disconnectedness has been a long time coming as smartphones and other screens dominate the lives of so many at work, at home and during social interaction. The pandemic supercharged screen use, for better and for worse.

A new study from the nonprofit group Kids Cout North Dakota released in September finds that mental health conditions for youth have worsened in the past five years, with 23% of children and adolescents in the state suffering from one or more mental health conditions.

More than 35% of high school youth in North Dakota reported feeling sad or hopeless each day for more than a two-week period last year, and 18% of high school students seriously considered suicide in 2023, according to the data.

There are many more variables besides screen time alone, however. Those can range from issues with bullying, to insecure home environments that may include abuse or addiction, to poor diets or lack of nutrition, to sedentary lifestyles, to a sense of isolation from family and friends.

Widening gaps

The report also found gaps for youth in accessing mental health services in the state.

A total of 21 counties have no mental health providers specifically working with youth and 46 counties have mental health care worker shortages. That means fewer social workers, clinical counselors and school psychologists available to see kids with the greatest needs.

Due to those gaps, youth often rely on school counselors or other teachers for mental health support.

A total of 35 counties do not meet the American School Counselor Association recommended ratio of one counselor to 250 students. This leaves around 87% of students in North Dakota’s public schools underserved.

Nick Archuleta, president of educator advocacy group North Dakota United, said he believes schools in the state don’t have enough counselors and most have a wide range of duties besides meeting with youth with emotional, behavioral or socialization issues.

Many, particularly in the high schools, also counsel on career and college choices, proctor tests and hold other titles within a school.

“North Dakota’s school districts are under increasing pressure to recruit counselors and social workers given the increasing range of issues that young people are bringing to school,” Archuleta said. “In many cases, schools are hard-pressed to find qualified individuals to work in their schools as there is a shortage of individuals entering that profession.”

Archuleta said this can be addressed in the upcoming legislative session and hopes policymakers can find ways to incentivize that career path.

Jered Bollom, president of the North Dakota School Counselor Association and elementary school principal in Elgin, as well as the lone K-12 school counselor in Grant County, said more needs to be done to increase the number of people training to become school counselors.

Currently only four higher education programs in the state offer school counselor training. One of those programs recently had no students, and another is fully online so offers limited in-person experience, he said.

Like Boesl, Bollom has seen changes in the youth mental health landscape over his past decade as a counselor, particularly in the pandemic period.

“To some degree, what we’re finding is that isolationism has been a big thing,” Bollom said.

It has been harder to get people back together and have kids open up after the pandemic, he said.

Bollom said it is important for families to teach digital citizenship to their kids and be role models for positive screen use, otherwise kids will mirror the behaviors of their parents.

“It’s an amazing machine that you can hold in your hands, but the responsibility with that is intense,” Bollom said.

Ideally the state could increase the numbers of social workers and school psychologists along with school counselors to form a three-pillar system of support for those with mental health challenges, he said.

Nationally, a bipartisan act called the Mental Health Excellence in Schools Act aimed at increasing the pipeline for individuals training to become school psychologists, counselors, and social workers by covering some graduate program costs was introduced in the Senate in 2021. The act was reintroduced in 2023, but has so far not gotten traction.

U.S. Senator Kevin Cramer (R-ND), whose own son Ian Cramer has suffered high-profile mental health and addiction issues, supported the reintroduction of the act in May of last year.

Looking ahead to the next legislative session, Bollom hopes more can be done to validate the roles of each of those pillars at the state level.

“If you want to help us do our jobs better then let us do what we’re supposed to be focused on doing,” Bollom said. “We can help the schools by being able to do what we’re doing, not five other jobs on top of that.”

While welcome, simply increasing access to treatment or the number of school counselors “is not going to solve everything,” said Xanna Burg, director of Kids Count North Dakota.

Holistic system-wide approaches need to be considered.

“There’s so much to the protective and prevention factors, and the social and economic factors that impact youth mental health around housing and food security,” Burg said.

Falling through the cracks

The Kids Count report also highlighted that barriers to support and treatment were highest for youth of color and LGBTQ+ kids in the state.

Native American youth, for example, had the highest rates of reporting their mental health as “most of the time or always not good,” according to the study.

LGBTQ+ youth are far less likely to talk with parents about feeling sad, hopeless, empty, anxious or angry. Between 6% and 8% say they would, compared to 22% of straight kids.

The study found that between 66% and 71% of LGBTQ+ youth reported feeling sad or hopeless almost every day, compared to 33% of straight youth.

Faye Seidler, community uplift program manager for Harbor Health Initiative in Fargo, said she’s been tracking similar numbers over the past several years so wasn’t surprised by the Kids Count analysis.

“We keep seeing the same outcomes with a lot of our kids experiencing bullying, sexual abuse, suicidal ideation, instances of violence from their family and not feeling safe at home,” Seidler said.

“It’s worth noting that it’s not all of our kids, there’s quite a lot of kids that still have good outcomes in the state and good, safe, supportive parents,” Seidler said. “It just continues to say that we could do a lot more for helping our kids in the state.”

One low-hanging fruit Seidler and Burg noted could make a difference would be addressing food insecurity.

“Food security is what I’ve come across as maybe the big, easy solution for a lot of good,” Seilder said. A recent nationwide survey of 1 million post-9/11 veterans showed how addressing food insecurity significantly reduced suicidal ideation among that group, Seidler pointed out.

On a more elemental level, simply finding connection and reducing isolation could go a long way toward addressing mental health challenges both for youth and adults, Boesl said.

That means quality time over meals and bonding as a family without being glued to a screen.

“I do think the family unit, the family systems, is where we need some help, and that’s where some of the trouble is,” Boesl said. “Just eating that meal together, without your phone. If I could prescribe that for everybody, I would.”

If you or someone you know may be considering suicide or is in crisis, call or text 9-8-8 to reach the Suicide & Crisis Lifeline.

The North Dakota News Cooperative is a non-profit news organization providing reliable and independent reporting on issues and events that impact the lives of North Dakotans. The organization increases the public’s access to quality journalism and advances news literacy across the state. For more information about NDNC or to make a charitable contribution, please visit newscoopnd.org.

The North Dakota News Cooperative is a new nonprofit providing real journalism about North Dakotans for North Dakotans. To support local journalism, make your charitable contribution to www.newscoopnd.org.

External

Talking Circle

At Buffalo's Fire we value constructive dialogue that builds an informed Indian Country. To keep this space healthy, moderators will remove:

- Personal attacks or harassment

- Propaganda, spam, or misinformation

- Rants and off-topic proclamations

Let’s keep the fire burning with respect.

In September, at least 73 Native people were reported missing in North and South Dakota — 65 are children

MMIW Search & Hope Alliance coordinator discusses upcoming volunteer training and misconceptions about the role

Chef Nephi and UTTC students celebrate food as medicine

By blending tribal regalia with holiday tradition, Indigenous veterans in Oregon are creating a safe, inclusive space where children see themselves in the magic of Christmas.

Thousands of Natives expected to camp, bring horses, tell stories about Custer’s defeat