Lower Brule Sioux Tribal Vice Chair Cody Russell testifies at Feb. 22 Lyman County Commission meeting with four of five commissioners present. Photo: Talli Nauman

Buffalo’s Fire

KENNEBEC, S.D. – The Lower Brule Sioux Tribe is awaiting South Dakota Gov. Kristi Noem’s decision on the legislature’s last-minute county districting amendment. Lyman County promoted the legislation knowing its passage will deprive two new majority Native districts the chance to elect commissioners here in the 2022 and 2024 runoffs. The bill also has ramifications for other counties with tribal lands across the state.

“After failing to give Native American voters notice to participate in the discussion, South Dakota legislators railroaded House Bill 1127 into law, recreating the rules for county redistricting at the eleventh hour with no justification and increasing the likelihood that counties will discriminate against Native voters,” said Native American Rights Fund Staff Attorney Samantha Kelty.

The House of Representatives originally approved it with the title “An Act to Enhance South Dakota.” The lone Democrat on the Senate State Affairs Committee, Rosebud Sioux tribal member and Senate Minority Leader Troy Heinert then secured a public hearing. The tribe and Native voting rights advocates testified against it at the committee meeting where it was amended and approved March 2. Labeled HB 1127, it moved on to garner full Senate and House support on March 7. From there it went to the governor’s desk.

Among witness criticisms was the use of an eccentric process to introduce it late in the legislative session. Kelty questioned this “unusual and secretive legislative process.” Adoption will further bolster the tribe’s potential Voting Rights Act Section 2 case against the county, she said.

The process that produced the bill goes by the name of hog-housing in South Dakota. A lawmaker introduces legislation with no content, just a title — in this case “Enhance South Dakota”. The bill — also known as vehicle or carrier legislation — passes through a legislative chamber in time for the mid-session deadline to keep it alive. Then, a last-minute text is inserted, so that that legislation can be adopted when it is least expected.

“If the bill’s sponsor would like to upend redistricting for every county in the state, such a measure should be proposed for the 2030 redistricting cycle so that all county constituents will have time to read, study, and mobilize in favor or against the proposal,” Kelty testified.

“Native voters will be denied their rights, and the county will continue to violate federal law, for the next four years.”

Lower Brule Sioux Tribal Vice Chair Cody Russell

Speaking on behalf of the Rosebud Sioux Tribe, Native voting rights consultant Bret Healy concurred, “Again, this is after the buzzer, changing the rules. Nobody would ever accept that in a basketball game. Nobody should accept it in this setting either.” He warned that taxpayers have had to foot the bill for past Voting Rights Act violations harming South Dakota’s largest minority, the Native American population. Counties tax constituents for liability insurance, he noted.

Both proponents and opponents agreed that the legislation has implications for redistricting in 15 other counties, nine of which have Indigenous majority communities in them. Some of those counties, like Lyman, elect commissioners using the at-large method. That means candidates from anywhere in the jurisdiction can receive votes from everywhere across the county.

HB 1127 amends South Dakota Codified Law 7-8-10 — governing the mandatory decennial revision of commissioner districts. It adds statutory language explicitly providing that, commissioners can decide whether their seats are “elected from single-member districts, from multi-member districts, or from a hybrid plan of single- and multi-member districts.”

Lyman County’s counsel Sara Frankenstein testified on commissioners’ behalf. “Counties need the flexibility to be able to determine what’s best for their constituents, their tribes, and others,” she said. “I’m here to ask you to change state law so we can do that.”

Lower Brule Sioux Tribal Vice Chair Cody Russell responded, “South Dakota law already allows” commissions to opt for at-large or districted voting. Currently, statute language binds the boards to “change the boundaries of the commissioner districts if such change is necessary” or “choose to have all of its commissioners run at large,” no later than February the year after release of each decennial U.S. Census.

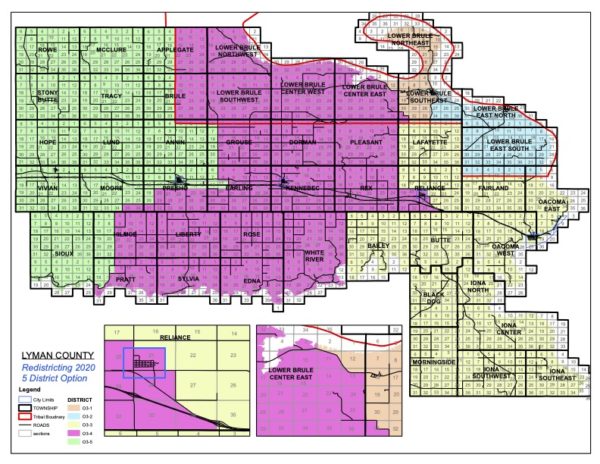

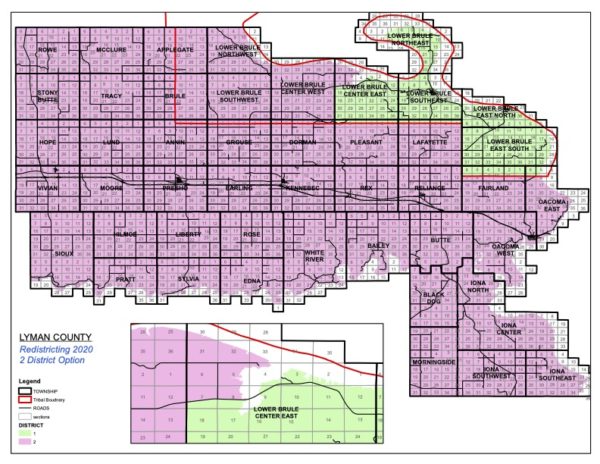

In October of this districting cycle, the Lower Brule Sioux Tribe requested that Lyman abandon at-large elections for its five commission seats in favor of five single-member districts of similar population size. Since the Native band’s jurisdiction is the most densely populated in the entirely rural county, it merited two districts, each with more than 90-percent Indigenous voting-age constituents.

Lower Brule passed a tribal resolution Feb. 9 opposing the hybrid arrangement and sent it with a letter to the same effect to Lyman County. However, commissioners determined that the two-district map would be better.

One district covering most of the Indian reservation would have two commissioners at large. The other would encompass the rest of the county and be represented by three commissioners elected at large. They called this a hybrid districting scheme – neither single-member nor at large, rather multi-member.

Ultimately, instead of approving either the tribe’s five-district proposal or the two-district plan, the commissioners unanimously passed an ordinance on Feb. 22 that favored the two-district boundary; it offered a map similar to Lower Brule’s idea as a “contingency” plan. The final decision depends on whether the county convinces the state to amend statute to specifically authorize the hybrid bid, Lyman County Auditor Deb Halverson told Buffalo’s Fire.

Russell objected, telling the Senate committee, “The county relied on the possibility that this bill could pass to delay using any commissioner districts until after the 2022 elections. Because county commissioner races are staggered, Native voters will not have the chance to elect the two representatives that we should have — until 2026,” he testified. “Native voters will be denied their rights, and the county will continue to violate federal law, for the next four years,” he said.

Kelty said passage of the amendment combined with the ordinance’s timeline for staggered elections would effectively be “robbing Native voters in the county of one seat for two years and of a second seat for four years.”

In deference to that situation, the ordinance’s last clause stipulates that “a tribe-appointed, non-voting liaison may attend the Lyman County Commissioners meetings and contribute to ensure fair representation to all Lyman County residents,” until such time as Native-preferred candidates can run for office. “This is the next best thing” so that Native constituents can “have a seat at the table,” Frankenstein told Buffalo’s Fire.

Both maps contained in the ordinance secure two seats on the commission for Lower Brule voters, who have never before been able to elect a Native-preferred candidate under the at-large system. “In either case, Native voters would have an opportunity to elect two candidates,” Kelty explained. “But the hybrid plan has the distinct disadvantage of racially segregating the county into a white district and a Native district,” she said.

Russell said it would amount to “segregating us and deepening existing tensions between our two communities.” With the county’s voting age population about 40-percent Native American, the tribe has long sought to “maintain a cooperative and productive relationship with the county, its commissioners, and our off-reservation neighbors,” despite disenfranchisement, he said.

He told Buffalo’s Fire the tribe seeks to minimize polarization and hopes to avoid a Section 2 Voting Rights Actlawsuit. However, Lower Brule Tribal Attorney Randy Seilers warned senators that passage of the bill is like “buying a lawsuit.”

Several witnesses, including O.J. Semans of the non-profit Four Directions, spoke in favor of the Lower Brule Tribe’s stance. Registered Advocate Ross B. Garelick Bell backed Lower Brule on behalf of the Oglala, Crow Creek, and Yankton Sioux tribes, as well as the non-profit NDN Collective.

After the Senate Affairs Committee heard the testimony, Heinert moved to table the bill on grounds that statute does not prohibit counties from changing to either at-large balloting or any districting formula. The motion failed, with only his vote in favor.

The committee adopted the amendment, 7-1, with a new title, “An Act to Modify Provisions Related to County Redistricting.” The Senate approved it, 22-13, and the House voted, 52-18, to send it to the governor.

Lower Brule Sioux Tribal Vice Chair Cody Russell gave Buffalo’s Fire this statement: “The South Dakota Legislature passed a bill that makes it harder for the Lower Brule Sioux Tribe and other tribes to participate in the county redistricting process. For months our tribe has been providing feedback on proposed county maps. The timing of HB 1127 is designed to make it easier for counties to discriminate. It is not surprising that this bill was passed without opportunity for full public consideration or input. Tribes should not back down and should continue to monitor all county maps produced in this redistricting cycle, regardless of how hard South Dakota tries to hide them.”

Talli Nauman is a Buffalo’s Fire contributing editor. Contact her at buffalo.gal10(at)gmail.com