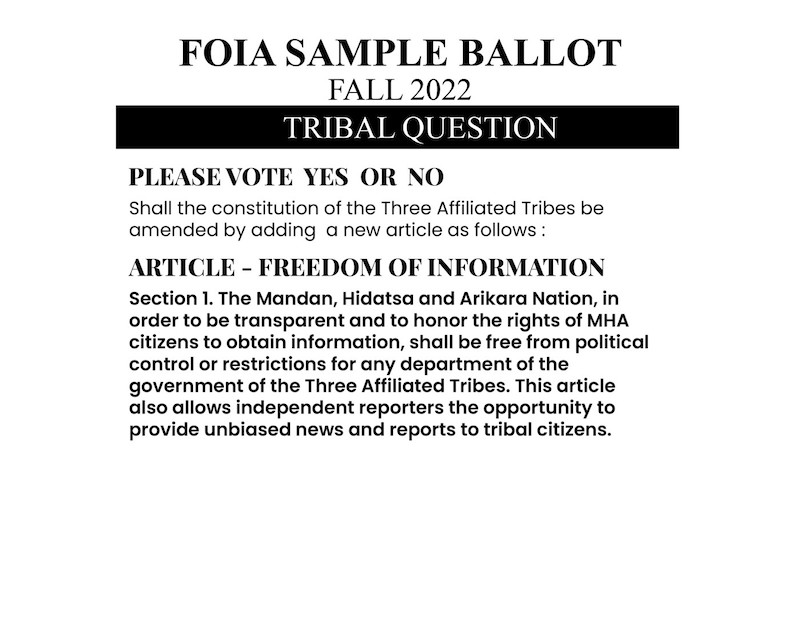

The Indigenous Media Freedom Alliance plans in fall 2022 to bring a ballot measure to tribal citizens of the Mandan, Hidatsa and Arikara Nation of the Fort Berthold Reservation in North Dakota. We’re asking voters to support a Freedom of Information Act so all citizens have access to government-related activities.

Ballot measure can provide avenue of transparency in local tribal government

The Indigenous Freedom Media Alliance is planning to bring together the clans, societies and community members of the Fort Berthold Reservation for a discussion on issues important to our citizens. As executive director and founder of the IFMA, my intent for the meeting is to create a space in which cultural leaders will guide the process of sharing ideas.

As a nonprofit media manager, planning this community gathering marks a new direction in my media life. Long before this moment, my reporting world revolved around a common journalism mantra: Stand aside and report objectively on a typical he said-she said story. After more than a decade of upheaval in the media industry, however, newspaper leaders are shifting the way they communicate with readers. Many now successfully model new methods of community engagement.

I am learning from leaders within the vanguard. It’s been liberating to take an active role in advocating for open records in order to improve the quality of life for people of the Three Affiliated Tribes. Since becoming a John S. Knight Community Impact Fellow at Stanford University in September 2021, I’m thankful to be among a cohort of 10 fellows to share ideas and draft new futures for each of our communities.

For my community that means I am free to explore changes that are needed on a systemic level. I live on the Fort Berthold Reservation in North Dakota where we have no Freedom of Information nor Sunshine laws. Across most of Indian Country, this same problem exists.

Of 576 federally-recognized tribes in the United States, about half of the tribal constitutions offer “passive” press freedom protections, meaning the documents contain ineffectual provisions for press freedom, right of assembly and free speech. Meanwhile, the other 50 percent of constitutional provisions range from silent to deferred, the latter referring to a U.S body of law outside the tribe, according to early research findings of Bryan Pollard, a former editor of the Cherokee Phoenix and lead researcher for the Red Press Initiative.

A small minority of those constitutions have “affirmative” provisions, or press freedom protection of the highest order. Pollard, who is also a former JSK Fellow, is researching tribal constitutions and press freedom. In short, Indian Country operates largely without a viable Fourth Estate, a networked free press responsible for providing a “public check on the branches of government.”

Since the JSK Fellowship began, I’ve been rethinking my role and responsibility as a journalist in a community with no Freedom of Information or Sunshine laws. I wrote about this issue in a Medium post about tribal news deserts. I’m now taking steps forward to create a Freedom of Information ballot measure for the Mandan, Hidatsa and Arikara Nation, the Three Affiliated Tribes.

As a tribal citizen, I choose to act in service to my tribe. This means acting in accordance to the will of the people. This means upholding a vital pillar of tribal sovereignty. This means listening to the people.

As a digital news entrepreneur, my JSK Fellowship network has provided tools and information — thanks Bolder Advocacy — to help me not just envision a better future for my community, but to take action. We’re now drafting legal language for a Freedom of Information ballot measure for the MHA Nation.

If any tribal leader wants to be considered a genuine leader — if they uphold the three tenets of tribal sovereignty — they will support and adopt Freedom of Information codes, acts and laws for their tribal citizens. On March 5, with President Vladimir Putin waging war in Ukraine, a Committee to Protect Journalists headline stated: “Putin has plunged Russia into an information dark age.”

CPJ adds: “For his last two decades in power Putin tolerated a handful of critical news outlets that provided a trickle of truth in a sea of state propaganda. But this legislation and website blocking have effectively dried up the free flow of information.”

As a journalist in no-FOIA zone, and as a tribal citizen, I live in an information dark age. Without Freedom of Information Act laws, it’s nearly impossible to receive or report on activities of the tribal government. A tell-tale sign of any dictatorship is to control the media. I read about other oppressive media environments around the world, a sorry reassurance I’m not alone. I find some gritty solace in Mikal Hem’s book, “How to be a Dictator: An Irreverent Guide.”

Hem writes: “Obviously, as dictator, one should strive for the least possible transparency. Budgets and accounting should be treated like state secrets, and the media should be kept utterly in the dark. (Then again, the media should already be under such strict control that no request for insight is made.) It is especially important to keep a lid on agreements surrounding the exploitation of natural resources. As a rule, these agreements are made between large international corporations and local governments.”

The Fort Berthold Reservation is an industrial corridor for multinational oil corporations. The Three Affiliated Tribes Tribal Business Council — the governing body of the MHA Nation that controls legislative, executive and wields a heavy hand with the judicial branch — has been in control of billions of dollars in oil revenue and royalties for more than a decade.

I’m about halfway through the JSK Fellowship at Stanford. It’s provided a tool box of leadership skills. It’s my goal to replicate the hard work of successful press freedom campaigns undertaken by my media colleagues among the Cherokee, Osage, Muscogee, Grand Ronde and Navajo newsrooms. I envision the day when their work can be replicated on my reservation and across Indian Country.

Jodi Rave Spotted Bear is the founder and director of the Indigenous Media Freedom Alliance. The IMFA publishes on buffalosfire.com. Jodi is a 2021–2022 John S. Knight Community Impact Fellow and a 2021 Bush Fellowfor leadership ending in 2023.

© Buffalo's Fire. All rights reserved.

This article is not included in our Story Share & Care selection.The content may only be reproduced with permission from the Indigenous Media Freedom Alliance. Please see our content sharing guidelines.