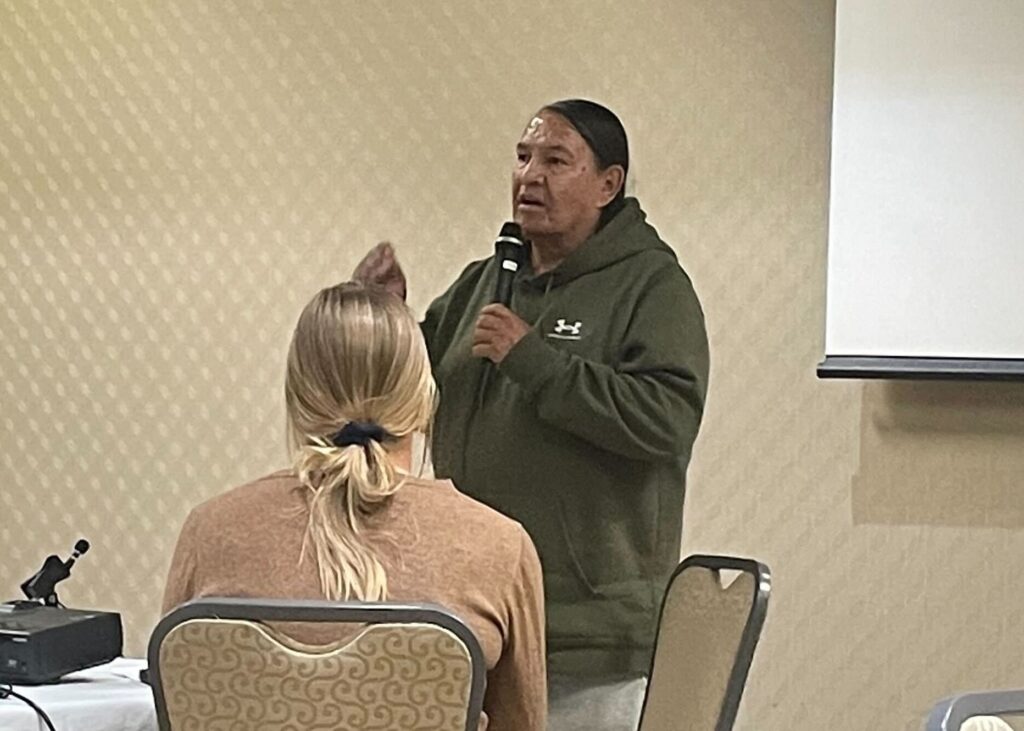

Local residents addressed the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to oppose the Dakota Access Pipeline during a set of two public hearings at the Bismarck Radisson Hotel on Nov. 1 and 2. Photo credit/ Adrianna Adame

The majority of local residents who recently addressed the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers spoke in opposition to the Dakota Access Pipeline — although tens of thousands of public comment letters have been submitted — during a recent set of public hearings at the Bismarck Radisson Hotel on Nov. 1-2.

Three years after a federal judge ordered a full environmental review of the pipeline, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers is wrapping up its Environmental Impact Statement with the public hearings before deciding whether the pipeline should continue to run underneath the Missouri River upstream from the Standing Rock Sioux Reservation.

In November 2016, at the height of the Standing Rock protests and after the Standing Rock Reservation had filed a lawsuit to stop the pipeline construction, the Obama administration halted the pipeline for additional discussion and analysis. Shortly after taking office, however, Donald Trump reversed that decision, and work on the pipeline proceeded. The pipeline was finished and has been in operation since 2017.

If finished as planned, the Dakota Access Pipeline would be a 1,168-mile system that would carry up to 750,000 barrels per day of U.S. light sweet crude oil from the Bakken and Three Forks production region of North Dakota to Patoka, Ill.

The five possible options the Corps is considering for the pipeline include digging it up, abandoning it, leaving it as is, increasing regulation, or re-routing it to avoid contaminating water supplies, north of Bismarck. More than 55,000 written letters have already been submitted, in addition to private tribal meetings, according to the Army Corps. The Omaha District conducted two virtual public meetings on Oct. 15-16, 2020 and one tribal meeting on Oct. 13, 2020.

In last week’s public hearings, everyone who spoke was timed for three minutes to speak with the court reporter before being cut off. When Joe Lafferty, a citizen of the Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe, walked to the front of the room, he asked the public to raise their hands if they supported the pipeline. One man raised his hand. When he asked the opposite, most of the room raised their hands in opposition to the pipeline.

“The treaties are an environmental impact statement that we need to stand on,” said Lafferty. “The point is we don’t want this pipeline on our land.”

The Fort Laramie Treaty of 1851 and 1868 defined the boundaries of tribal land. In the 1851 agreement, the United States acknowledged the territorial claims of the Plains tribes. Originally the purpose of the treaty was to negotiate the rights to passage through Indian Country for westward-bound emigrants, according to the National Park Service. Chiefs from the Cheyenne, Arapaho, Crow, Lakota,, Assiniboine, Mandan, Hidatsa and Arikara signed the treaty. More than 10,000 Plains Indians made the trip to Fort Laramie in Wyoming to attend the great treaty council. Due to the high number of attendees, the site was moved to Horse Creek some 30 miles south of Fort Laramie

The 1868 treaty recognized the Black Hills as a part of the Great Sioux Nation, allowing only authorized people to enter the Black Hills and any land within the reservation.

The treaties are more powerful than the authority of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, said Lafferty. The treaties cover the environment and all the people and wildlife who are living on the land.

“I want to remind you that you have a boss, and that’s the Congress of the United States of America,” Lafferty told the Army Corps representatives facilitating the meeting. “For you guys to give that permit [easement] –– you’re overstepping your bounds of authority.”

Despite the Army Corps representatives announcing they wouldn’t be answering questions from the public, Tyrel Iron Eyes was in search of answers. One of the questions he asked the Corps was if the pipeline easement is currently vacant. Sheila Newman, the Army Corps operations division chief, said yes.

“I don’t want this pipeline to succeed. I don’t want there to be oil under that area,” said Iron Eyes. “For my entire life, that river has been a source of my livelihood.”

Iron Eyes said Natives and non-Natives alike shouldn’t have to wait for a disaster to happen if they can prevent the pipeline now. A majority of people who reside in the area, including the tribes whose territory lies alongside the pipeline’s path, would be affected and face any potential consequences if there were a leak.

The pipeline poses a risk for pollution across tribal lands, wildlife habitats, sacred sites and the Missouri River, according to the Center of Biological Diversity. The pipeline would also run through Lake Oahe, a large reservoir in North Dakota. “We shouldn’t have to be this concerned,” said Iron Eyes. “We shouldn’t have to fight over water or our right to exist.”

Matthew Borke, a water protector and demonstrator, wants the Corps to understand who they’re talking to. He spoke out against the use of guns and tear gas during protests, particularly during the #NoDAPL protests in 2016. More than 300 injuries and 800 arrests occurred in Standing Rock between 2016 and 2017.

“Nobody wants a war, we’re not here to kill each other,” said Borke. “We’re actually doing the opposite of that; we’re trying to communicate to save the next seven generations and the generations beyond that.”

Billi Jo Beheler, the co-founder and executive director of Oun, a non-profit community development organization, criticized the lack of translators at the public hearing. Prior to the meeting, she and others asked the Corps representatives for translators for their Lakota and Dakota elders.

“We shouldn’t have to be this concerned, we shouldn’t have to fight over water or our right to exist.”

Tyrel Iron Eyes

Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 prohibits discrimination on the basis of race, color, and national origin in programs and activities receiving federal finance assistance. According to the U.S. Department of Justice, federal agencies are required to provide Limited English Proficient individuals with meaningful access to their programs and services, which includes services for oral interpretation and written translation of vital documents.

“Why didn’t we get a translator for our Lakota and Dakota speakers? Because nobody thought about it,” Beheler said. “The livelihoods of our communities have always been an afterthought.”

Oscar High Elk, a citizen of the Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe, spoke of protecting the water and land for the next seven generations. The seven generations principle is an Indigenous concept that encourages people to practice sustainability by protecting water, energy and natural resources for future generations.

“This is a way of life for us, this isn’t something we decided to do recently,” High Elk said.

Attending the public hearing is only the beginning of this next chapter of battling the pipeline. “We’re not giving up. We’re not going to stop,” High Elk said.

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers comment period ends Dec.13. Comments can be emailed to NWO-DAPL-EIS@usace.army.mil.

https://cdxapps.epa.gov/cdx-enepa-II/public/action/eis/details?eisId=428178

https://www.nps.gov/articles/000/horse-creek-treaty.htm

https://www.nytimes.com/2016/10/29/us/dakota-access-pipeline-protest.html

https://www.nytimes.com/2016/10/29/us/dakota-access-pipeline-protest.html

https://hpr1.com/index.php/feature/news/more-than-two-years-later-last-nodapl-trials-finish/

https://www.justice.gov/crt/fcs/TitleVI

© Buffalo's Fire. All rights reserved.

This article is not included in our Story Share & Care selection.The content may only be reproduced with permission from the Indigenous Media Freedom Alliance. Please see our content sharing guidelines.