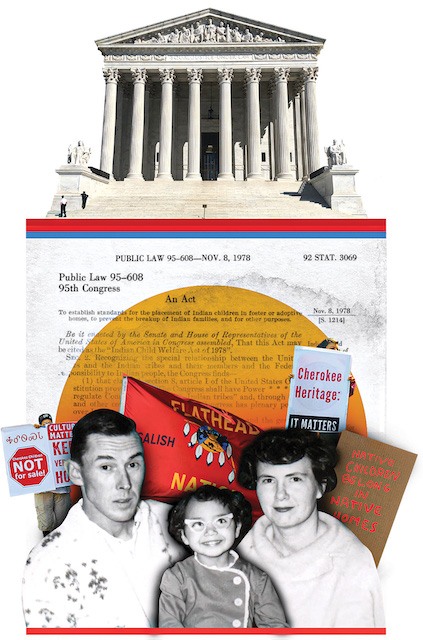

Can Indian Country withstand the new Supreme Court?

Nick Martin

High Country News

United States Supreme Court, Washington D.C.

The High Court is set to hear a case that will affect thousands of Native kids. Is it qualified to judge?

On Nov. 9, the eyes of Indian Country will once again turn toward the nation’s capital, where the Supreme Court will hear a challenge to the Indian Child Welfare Act (ICWA), a law passed in 1978 that enshrines tribal governments’ right to oversee foster care placements in cases involving Native children. The bill followed the damage done by the U.S. boarding school system and extractive adoption practices, which stripped Native youth of their culture and removed them from their communities. Since the case first appeared in a Texas district courthouse in 2018, conservative state leaders and think tanks have pushed the case to the highest court. Brackeen v. Haaland will determine whether tribal nations maintain the right to intervene in foster and adoptive cases to ensure Native children are placed with Native families.

For Susan Harness, a member of the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Confederated Tribes and a survivor of the pre-ICWA adoption era, the immediate stakes of it being struck down are clear.

“It will open the floodgates to cultural annihilation,” said Harness, who wrote about her experience in Bitterroot: A Salish Memoir of Transracial Adoption. “The Indian adoption project, the social experiment that happened between 1958 to 1967 — kids went flying off the reservation. … When that happens, you grow up hating yourself, because you are now being raised in the colonizers’ belief system of how awful you are, not just as a human being, but as a piece of culture that should have died out a long time ago.”

On its own, Brackeen is a legal and political challenge to the health of Native kids, tribal nations and communities. But after the recent rush of appointees to the bench by Donald Trump and Joe Biden, Brackeen also represents a test of what this young court means to the future of tribal sovereignty. In a worst-case scenario for Indian Country, the court could strike down the law on equal-protections grounds, arguing that the ICWA is unconstitutional because Native citizens are a racial, not a political, class. This would, intentionally or not, undercut the nation-to-nation relationship tribes hold with the federal government.

HAD THE BRACKEEN CASE appeared on the court’s docket two years ago, fresh on the heels of the now-famous McGirt decision — in which Trump-appointee Neil Gorsuch functionally served as the swing vote when the court held 5-4 that the Muscogee (Creek) Nation Reservation was never disestablished by Congress — this ICWA challenge, and any subsequent challenges to tribal sovereignty and Indigenous human rights, might not be as worrisome.

“Then Justice Ginsburg died.”

That’s how Elizabeth Hidalgo Reese, a citizen of Nambé Pueblo and a law professor focused on tribal, constitutional and federal Indian law at Stanford University, put it over the phone in August. Support for tribal sovereignty doesn’t fall along partisan lines, and Ginsburg’s rulings didn’t always favor tribal sovereignty: In 2005, she wrote the majority opinion in City of Sherrill v. Oneida Indian Nation of New York, holding that the Oneida Nation of New York could not establish sovereign rule over stolen lands the tribal government had repurchased. Similar examples abound from her contemporaries: Justice Clarence Thomas continues to hold that the 1871 Indian Appropriations Act should effectively negate most of tribal nations’ claims to sovereignty, and Justice Stephen Breyer, in his opinion on Baby Girl, a previous ICWA challenge, entertained the idea that some conniving tribes would act against a child’s best interests.

But with Ginsburg and the other justices in place, the bench’s behavior was predictable enough for tribal nations and organizations to make an informed decision about their legal strategies. Ginsburg’s passing upended tribal nations’ calculus regarding the court. Conservative Justice Amy Coney Barrett, appointed to replace Ginsburg in October 2020, gave the bench’s conservatives a 6-3 edge and lacks experience in Indigenous cases. Fellow Trump appointee Brett Kavanaugh is similarly green, and Biden’s appointee Ketanji Brown Jackson also has little tribal expertise — a pattern Reese said that is caused in part by a system-wide dismissal of federal Indian or tribal law curriculum.

“Every law student in this country tends to walk into a law school classroom and get told that there’s two types of law in this country, that there’s state and there’s federal law, period,” said Reese. “There are 574 tribal governments across this country who are also making laws to govern their communities — (law schools) just pretend like we don’t exist, like we don’t control as much land as the state of California. It’s insane.”

The ramifications of the court’s inexperience were on full display in June, when in Castro-Huerta v. Oklahoma, it broadly declared, by a 5-4 vote, that state law enforcement agencies have the right to prosecute crimes committed by non-Natives against Native citizens on tribal lands. Kavanaugh penned the majority opinion, which Reese described as “a tad bit sloppy yet overconfident” in how unconcerned it seemed with the potential ripple effects. In a dissenting opinion, Gorsuch referenced the 1832 Worcester decision, writing, “Where our predecessors refused to participate in one State’s unlawful power grab at the expense of the Cherokee, today’s Court accedes to another’s.”

“There are 574 tribal governments across this country who are also making laws to govern their communities — (law schools) just pretend like we don’t exist, like we don’t control as much land as the state of California. It’s insane.”

Elizabeth Hidalgo Reese

The outstanding question ahead of the Brackeen hearings is not whether the court will strike down the ICWA — Reese said it almost certainly will — but how far the majority will reach with its ruling. If the court ruled on equal protection grounds, even if justices limited their ruling to the ICWA, Reese said the natural question — one that an emboldened state attorney general or radical think tank would surely ask — is what other laws and federal policies could be challenged on similar grounds. If the court strikes down the ICWA under Article 1 of the U.S. Constitution, which permits Congress ultimate governing authority, and finds that Congress overstepped the broad authority granted to it by the Indian Commerce Clause, it would also open the door for every federal law concerning Native peoples and nations to be challenged.

“The people who object to our status as sovereign nations, they fully understand that one of the most effective ways to dismantle tribal governments is to go after our children,” said Allie Maldonado, the chief judge of the Little Traverse Bay Bands of Odawa Indians. “They are our future. There is no other way for us to continue our governments, our language, our culture.”

Another potential outcome, which Reese described as “the way to lose and have it not be devastating for the rest of Indian law,” is that the court takes up the case on commandeering grounds — the 10th Amendment holds that Congress cannot force state governments to carry out federal policy aims, as a portion of the Brackeen challenge claims the ICWA does. While Reese noted that the justices are certainly more familiar with states’ rights cases, their collective track record, Castro-Huerta included, doesn’t leave much breathing room for the ICWA.

On the other hand, the court could reject the Brackeen challenge altogether and hold that the ICWA is constitutional law that is neither race-based nor a violation of state sovereignty. This would temporarily stave off the vultures attacking tribal sovereignty and Native children — at least until the court’s next session.

“It’s a minefield,” Reese concluded — one that nine non-Native justices will sprint through in a month.

Sarah Trent contributed reporting to this article.

Nick Martin is an associate editor for HCN’s Indigenous Affairs desk and a member of the Sappony Tribe of North Carolina.