'Native teachings continue to live on' in project-based school born out of #NoDAPL movement

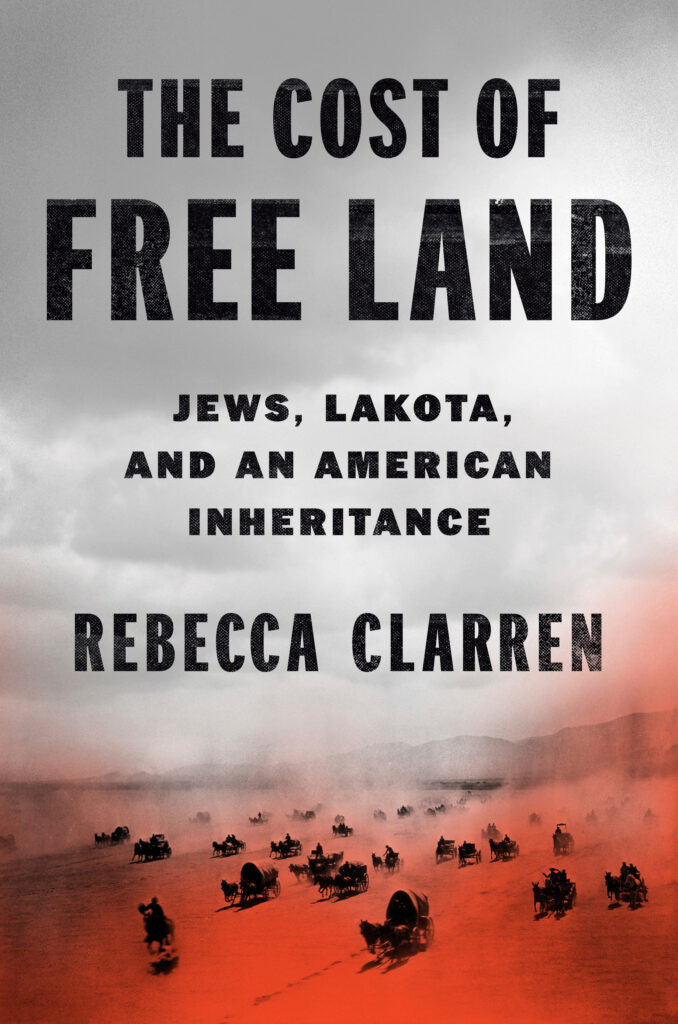

Rebecca Clarren’s next stop on her book tour for “The Cost of Free Land” is Bismarck on April 29, where she’ll be having a reading and open discussion about the dispossession of Indigenous land. Photo by Shelby Brakken, photo courtesy of Rebecca Clarren

“The Cost of Free Land: Jews, Lakota, and an American Inheritance” by Rebecca Clarren intertwines her Jewish ancestors’ immigration story, the United States government’s history of broken treaties with tribal nations, and the Lakota’s dispossession of land into a hard-hitting novel. According to the publisher’s website, the book “captures the devastating cycle of loss of Indigenous land, culture, and resources that continues today.”

Clarren, who will be presenting her book on Monday, April 29, at Bismarck State College, shared some of the book’s backstory in an interview with Buffalo’s Fire.

Growing up, Clarren only knew the basic facts of her family’s immigration origins. Her great-grandparents, the Sinykins, fled from Russia with their six children due to antisemitism at the turn of the 20th century. Eventually, the family of eight settled on a 160-acre homestead in South Dakota –– but she never knew what led her family to settle on that piece of land on the borders of Pennington and Haakon Counties about 13 miles southwest of the Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe Reservation.

Her family later moved to the Pacific Northwest before her birth.

Meanwhile, the award-winning author and journalist Clarren had written for years about tribal sovereignty and how certain federal policies impacted tribal nations, still affecting many Natives’ lives. “But for so long, I, like so many non-Indigenous Americans, thought about this history as having nothing to do with me,” she told Buffalo’s Fire.

“It took kind of an embarrassingly long time to realize, oh wait, I can find myself in this history…knowing what I knew about the Homestead Act and the Dawes Act and the history of land dispossession by the United States of Native peoples, I suddenly had this realization, oh, that huge benefit to my family, it must have come at great cost to our Lakota neighbors. And so that was really what inspired the book.”

During her research process, she dug through documents, land deeds, public records and data from the Bureau of Indian Affairs to determine which land belonged to Lakota citizens, such as the White Bull family, whose story she also mentions in the book. She was searching for hard data and answers to the questions that haunted her.

“The questions that I often say this book started with are, you know, what are the stories we tell in families and in nations, but also what are the stories we don’t tell? And why don’t we tell those stories?” Clarren said. “Because the myths that we’re creating about ourselves that we’re passing on to future generations, that’s created by both the stories we tell and the ones we don’t.

“I grew up hearing a lot of amazing stories about my family’s time in South Dakota, but I never heard anything from my family about the Lakota who lived nearby, or about where this free land came from. So the book was sort of an effort to fill in the white spaces at the edges of those narratives.

When Clarren’s family came to the United States, they were given “free land” in South Dakota. President Abraham Lincoln signed the Homestead Act in 1862, which provided 160 acres of surveyed government land to any adult citizen, or intended citizen, who had never borne arms against the U.S. government.

They just had to stake a claim to it. According to the National Archives, after paying a small fee, settlers would be recognized as owners of the land once they continuously resided there for five years. While 500 million acres of land was disbursed between 1862 and 1904. Eighty million acres went to homesteaders. Due to the ambiguous nature of the act, most of the land went to speculators, cattle owners, miners, loggers and railroads.

The Dawes Act of 1887, signed by President Grover Cleveland, allowed the federal government to break up tribal lands. The government granted individual allotments to Natives, encouraging them to take up agriculture and assimilate into American society. According to the National Archives, “It was reasoned that if a person adopted ‘White’ clothing and ways, and was responsible for their own farm, they would gradually drop their ‘Indian-ness’ and be assimilated into White American culture.”

Over a period of five years, the author overcame many obstacles while working on “The Cost of Free Land.” Several times, she rewrote the book. Her biggest fear was unintentionally creating more harm in how she told this story. “It felt impossible at the beginning,” said Clarren. “I really hoped that I could tell these histories side-by-side. I really wanted to grapple on the page with how to respond, and I didn’t want that to feel performative, and so I struggled.”

One of the biggest challenges she also faced was how she’d disentangle her family’s immigration story without minimizing Jewish immigrants’ experiences. “I meant for this book to be kind of a corrective to say that even though Jewish Americans have been very oppressed and are still oppressed, that doesn’t mean we can’t also be part of an oppressive system,” said Clarren. “I had to look at some of my own internalized antisemitism and had to be able to extend as much empathy to my own family as I was extending to the White Bull family.”

Though Clarren’s grandmother and her sisters sold the last piece of her family’s land in the 1970s, she said she felt a deep sense of empathy for the Lakota, whom the land previously belonged to. She spent a lot of time reflecting on how her family benefited from the land’s generational wealth.

Despite the harm caused in the past, she hopes this book does some good and is a positive learning experience for readers. “There was a lot of blood, sweat and tears that went into this book,” said Clarren.

The author hopes descendants of homesteaders will take the time to reflect and think about where their land came from. “Another key theme is looking at American history in a much more complex and nuanced way and pulling that history into this contemporary moment, seeing the connections between the past and now and thinking about how we can, by knowing that history, start to consider the future in a hopefully more compassionate and responsible way,” Clarren said.

Since the book’s release in October 2023, Clarren has been touring the country to discuss “The Cost of Free Land.” The author’s next stop is North Dakota.

Humanities North Dakota will host a book reading and open discussion with Clarren at Bismarck State College’s National Center Energy of Excellence in the Basin Auditorium on Monday, April 29, from 6 p.m. to 8 p.m. The in-person event will have “The Cost of Free Land” available for purchase, and attendees will have the chance to get their copy of the book signed by Clarren. Those interested in attending can sign up for a free ticket on the Humanities ND website.

Adrianna Adame

Former Indigenous Democracy Reporter

Location: Bismarck, North Dakota

See the journalist pageNational Archives and Records Administration. (n.d.). Dawes Act of 1887. National Archives. https://www.archives.gov/milestone-documents/dawes-act

National Archives and Records Administration. (n.d.). Homestead Act (1862). National Archives. https://www.archives.gov/milestone-documents/homestead-act

© Buffalo's Fire. All rights reserved.

This article is not included in our Story Share & Care selection.The content may only be reproduced with permission from the Indigenous Media Freedom Alliance. Please see our content sharing guidelines.

Curtis Rogers sets his sights on law school

Students use space to relax and connect to Native culture

New law requires schools to teach Native American history

Terrence and Patricia Leier are ‘giving back for the sacrifice that the Natives made’

Bush Fellow eager to draw more young adults to college