At the Crossroads: State of the Economy in Indian Country

‘Stealth’ economy for tribes hides billions of dollars in jobs, growth and revenue for rural communities

This story is part of a collaborative series, “At the Crossroads,” from the Institute for Nonprofit News, Indian Country Today and nine other news partners, examining the state of the economy in Indian Country. This reporting was made possible with support from the Walton Family Foundation.

Study after study reaches the same conclusion: Tribes are often the largest drivers of regional and rural economies.

In Oklahoma, a new report said tribes and tribal enterprises added $15.6 billion in direct contributions in 2019 to the state’s economy. In addition, many more billions were spent by suppliers and those developing products for the tribes. The result: “Oklahoma tribes support 113,442 jobs in the state, representing $5.4 billion in wages and benefits to Oklahoma workers. While direct employment exceeds 54,000 jobs, tribal investment spurs job growth in many different industries.”

What’s more, the Oklahoma tribes re-set the framework for healthcare.

“Tribal health care facilities provide increased access to care for tribal citizens in both urban and rural parts of the state,” the study noted. “Rural tribal populations are relieved of the stress of relocating to more urban areas to be near health care and thus may be more likely to remain in these rural areas …This has a profound impact on rural communities.”

The Oklahoma story is common.

A fun scroll: Google the words, “tribes” plus “largest employer.”

- The Iowa Tribe of Oklahoma is the largest employer in the area;

- The Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes are the largest employer in northwest Montana;

- The Oneida Nation is the largest employer in Oneida and Madison counties.

Then it’s a much longer list, especially when you add in qualifying phrases, such as “one of.”

That’s because tribal enterprises and governments are significant players in their regional economies and to the nation as a whole. But how much and where tribes contribute is a well-kept secret. There are no national numbers that chart the impact from tribal communities across the nation; no broad reports assess the impact or calculate the growth. There is a missing metric.

A rough assessment examining key economic drivers such as casinos and the hospitality industry, agriculture, fossil-fuel extraction and renewable energy development puts the economic impact of tribal communities into the tens of billions of dollars every year, not including small businesses, mom-and-pop stores and tribal government jobs. Government is often the largest employer in tribal communities.

One clue to the total economic picture is the $20 billion distributed to tribal governments, and enterprises via the American Rescue Plan. Another $12 billion came through the Indian Health Service and Bureau of Indian Affairs. That law used a formula that considered the number of employees as well as tribal citizens. Indian gaming is a $34 billion a year business (at least before the pandemic).

As a frame for comparison, the smallest state economy (or Gross Domestic Product) is Vermont at roughly $37 billion a year.

A study by Harvard and the University of Arizona’s Native Nations Institute described the changing nature of the economy.

“The economic gaps between Indian Country and the rest of the United States at the beginning of the self-determination era were so large that closing those gaps was taking time,” the study reported. “It is proper to say that the glass may have been only half full, but at least it was filling. In fact, in some cases, there was truly outstanding progress being made against the scourges of economic disadvantage.”

The institute also stripped away a popular myth about the economy in tribal nations, that tribes receive an unfair share of funds from the U.S. Treasury. “It is state and local governments that have received outsized support from the federal government,” the report said.

Clearly more data is needed.

This year, the Federal Reserve Bank’s Center for American Indian Development launched a long-term initiative “to address persistent data gaps that exist in Indian Country.”

“The lack of data in Indian Country limits our understanding of the economy,” said Neel Kashkari, the Minneapolis Fed president. The center is hoping to build a portfolio of research to help tribal leaders and other policymakers have a better understanding of the economy.

Indian Country Today and nine news partners are using another lens — looking at tribal and rural economies through regional and community efforts. This special report, “At the Crossroads,” which runs through Thursday, examines the state of the economy in Indian Country, its impact on local communities and what lies ahead for the future.

The series is part of a collaboration led by Indian Country Today with the Institute for Nonprofit News and its Rural News Network. News organizations participating in the collaboration included Buffalo’s Fire, InvestigateWest, KOSU, Mvskoke Media, New Mexico In Depth, Osage News, Rawhide Press, Underscore and Wisconsin Watch. The project was funded by grants from the Walton Family Foundation.

The findings were clear from region to region and tribal community to tribal community. There’s growing interest by tribes and enterprises to leverage profits from casinos to launch new businesses. There’s a push to create jobs in renewable energy. And tribes are exploring the dramatic shift in fossil fuel jobs by looking at other options, including development of an industry based on restoration and cleanup. Other economic ventures range from the role sports can play as a local job-creator, sustainable agriculture and partnerships that tribes can reach with local governments to put more tribal citizens to work.

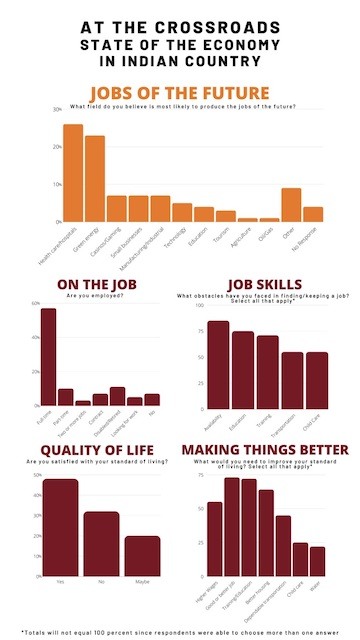

People in Indian Country clearly believe changes are ahead. A national survey conducted by Indian Country Today and the collaboration partners found that respondents believe healthcare and green energy are the jobs of the future, with casinos and the oil and gas industry slipping a bit in their domination of the workforce.

The survey, which was distributed nationwide, generated hundreds of responses from people representing more than 130 tribes in 38 states and the District of Columbia. More than 90 percent of respondents said they are tribal citizens or of tribal descent, and nearly three-fourths live on or near tribal lands.

The impact is clear: Tribal nations are important to the broader conversation about rural economies, according to a 2021 study by Stephanie Gutierrez and Miriam Jorgensen at the Aspen Institute.

“When Native nations thrive, they tend to lift up the non-Indigenous communities that are their neighbors,” Gutierrez and Jorgensen wrote.

“This is particularly true in rural areas, where Native nation governments, tribal businesses, and Native nation citizens represent a larger proportion of the local governance infrastructure, economy and population than in urban areas, and thus generate a larger share of local jobs, spending and tax dollars.”

Health care economics

One window into the regional economies of tribes – and the financial challenges of the pandemic – starts with healthcare.

Healthcare is already one of the largest employers in tribal communities. The federal Indian Health Service alone employs some 15,000 people across the country.

The grand opening last year of the newly constructed Little Shell Clinic in Great Falls, Montana, happened because of the pandemic.

The Little Shell Tribe of Chippewa Indians of Montana received federal recognition in 2019 and Chairman Gerald Gray pegged healthcare as the tribe’s top priority. But under the Indian Health Service system, the tribe would have been forced to wait perhaps decades before being included on the list for a new facility.

Then came the pandemic, followed by the Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economic Security Act – the CARES Act. Suddenly there was funding available to build a clinic.

But as the pandemic opened up one path, it added an obstacle for another — hiring enough people to staff the Indian Health Service clinic. The new facility has 52 staff positions, but faced with recruiting issues and supply chain problems, only about a third have been filled.

“They have hit some bumps in the road, of course, like with everyone, “ said Molly Wendland, Little Shell’s tribal health director.

At a recent meeting with other tribes, she said she heard the same story, the problem of hiring enough people to fully staff the Indian health care system.

“I agree the current and future demand for health care workforce is very good right now and optimistic into the future,” said Jim Roberts, Hopi, senior executive liaison for intergovernmental affairs for the Alaska Native Tribal Health Consortium. “The pandemic has also revealed opportunities that exist in the structure of IHS and the tribal health system.”

The use of community health representatives and other on-the-ground essential health workers is growing, he said.

“Medicaid has been trying to do this for years,” he said. “More can be done here. If there is one thing COVID unveiled, it was how fragile our health system is and a significant part of this is attributed to health professional shortage issues. Something IHS and tribes know all too well.”

Another solution to the staffing shortages is to expand opportunities for people to obtain the proper training and credentials. One possibility is to form an intertribal organization that prepares workers to get the appropriate credentials.

“Hiring in the long term is going to be incredible,” said Little Shell’s Wendland. “I think those roles are going to become even more important and [these are] positions that don’t necessarily require a degree.”

The Indian health system, especially at the tribal level, has already taken the lead. In Alaska, for example, a dental health therapy program has created an oral healthcare delivery system using mid-level practitioners who can be based within Indigenous communities, instead of using professional dentists from outside.

“But the IHS are slow-rolling the expansion and development of these programs to the lower 48 — and even in Alaska,” Roberts said. “Alaska funding for these very successful and effective programs has been stagnant for years, not to mention the disappointing appropriations by Congress to expand these programs to the lower 48 states.”

These sorts of programs could easily be replicated for rural communities across the country and provide jobs that can begin with post-high school training.

The pandemic also opened up funding for facility construction.

The Cherokee Nation recently announced construction of a new $400 million, in-patient hospital, just two years after construction of a large new outpatient facility. The hospital will be the tribe’s largest investment yet in healthcare.

Cherokee Nation Principal Chief Chuck Hoskins Jr. wrote in Newsweek about how the tribe used a pool of funds to improve both physical and behavioral health programs.

“Part of our allocation is supplementing our own efforts to build a new hospital for the Cherokee Nation Health System, the largest tribally-operated health system in the country,” he wrote. “Our current hospital is badly outdated and undersized for today’s patient population. Once the new hospital is operational, the old location will be repurposed as a hub for our mental health and addiction treatment services.”

Green jobs are the next wave

Renewable energy is also a growing component to the tribal economy. Solar energy is enjoying a boom in many communities, but tribes are also turning to wind, water and other sustainable approaches that protect the lands.

“I would love to get paid to help small homestead/hobby farmers (urban, sub-urban, rural) set up sustainable, eco-friendly installations, using a Native approach,” one person wrote in responding to the ICT survey. “It is very important for people to get back to the earth and learn tried and true strategies the Native people perfected.”

Minnesota’s Prairie Island Indian Community is doing just that with a Net Zero program. The goal is to measure and reconfigure the tribe’s energy needs to make it carbon neutral.

“You know, for me, it’s just reducing the impact on earth,” said Mike Childs Jr., assistant secretary and treasurer of the Prairie Island Tribal Council. “It’s just that simple to me, you know, trying to reduce the impact on earth.”

Prairie Island’s lands are next to the Prairie Island Nuclear Power Plant in Redwing, Minnesota. The tribe does not get any energy from that plant, but the proximity did open up a state funding mechanism for the Net Zero project.

“I think for me, the hardest part of the project has been just trying to figure out, you know, what the best way to reduce our carbon footprint is,” Childs said. “You don’t just throw up solar panels or whatever.”

It’s always cheaper to reduce energy consumption than to generate new power, he said, but the tribe took on a holistic approach beyond consumption. This included rethinking the use of food containers and other materials

“Sometimes we’re questioned because it’s more expensive,” Childs said. “But I mean, really, is it? Is it more expensive to have compostable containers or plastic … floating around in the Pacific Ocean?”

But some green energy options are raising questions about whether they are worth the long-term costs. Although lithium is considered key to the expansion of electric vehicles and electronics, a proposed lithium mine in Nevada would impact ancestral lands for several tribes in the region.

Growing opposition has left the project up in the air, despite pressure on tribes to support the project.

In New Mexico, however, cleanup of abandoned uranium mines is considered a job for today. With increasing demands for contractors to properly clean up the radioactive debris left behind by decades of mining, opportunities are expanding for local businesses and workers to do the job.

Beyond the horizon

Dramatic changes may be ahead for two industries, gaming and those related to extractive fossil fuels. Several folks responded to the ICT survey saying that more technology was needed to create the jobs of the future.

“Too many high school graduates end up pushing a broom at the casino [while] most professional technical and executive positions are occupied by non-Indians,” one respondent said.

People answering the survey said the time is right to make investments in what’s next, such as jobs that promote a healthier lifestyle, “deeply rooted in Indigenous beliefs and education.”

Even the $35 billion gaming industry – which dropped to about $28 billion during the pandemic – is going through changes that will impact Indigenous communities. Tribes are using the profits from gaming to generate capital, investing in ventures that put them in the ranks of America’s largest companies.

A great example of that is the tribal money going to investments in Las Vegas. Three major deals this year included the Mohegan Sun’s Virgin Hotel, the San Manuel Band’s Palm Casino Resort, and a yet-to-be-concluded purchase of a new property by the Hard Rock Hotel, which is owned by the Seminole Tribe of Florida. A fourth tribe, Fort Mojave, opened the Avi Resort & Casino in 1995 on tribal lands near Laughlin, Nevada.

Tribes are also ready to expand gaming beyond the casino experience, with a growing number of ventures offering sports betting.

Similar approaches are being used in other industries. Tribes from Florida to Alaska are launching energy projects from wind, sun and water, with a consortium of tribes in South Dakota working on a major wind farm that could power 1.5 million homes.

One example of the shift is the former Navajo Generating Station near Page, Arizona. The plant had been producing energy from coal but closed in 2019 after it became more difficult to sell that power source. The closure resulted in the loss of about 1,600 full-time jobs. Now, about 200 full-time jobs are associated with cleanup and reclamation efforts.

Back in Oklahoma, tribes are a significant employer, offering an employment base that would usually be sought after, with state officials asking for more.

But as the Indian Country economy remains in stealth mode … the opposite is true.

Oklahoma Gov. Kevin Stitt, a Republican, and a citizen of the Cherokee Nation, has gone out of his way to attack tribes on multiple levels from gaming revenues to criminal jurisdictions. In late March, the governor was on Fox News complaining that jurisdictional issues with tribes was tearing the state apart.

The hostility is such that the tribe tweeted back a response.

“As a tribe of 410,402 citizens, we’re thankful for the 410,401 Cherokee citizens who aren’t going on TV to undermine our rights and sovereignty.”

This story is part of a collaboration from INN’s Rural News Network in partnership with INN members Indian Country Today, Buffalo’s Fire, InvestigateWest, KOSU, New Mexico In Depth, Underscore and Wisconsin Watch, as well as partners Mvskoke Media, Osage News and Rawhide Press. Series logo by Mvskoke Creative. The project was made possible with support from the Walton Family Foundation.