Opinion Advocates for ideas and draws conclusions based on the author/producer’s interpretation of facts and data.

Ex-councilman’s prison sentence signals call to open tribal government records to public

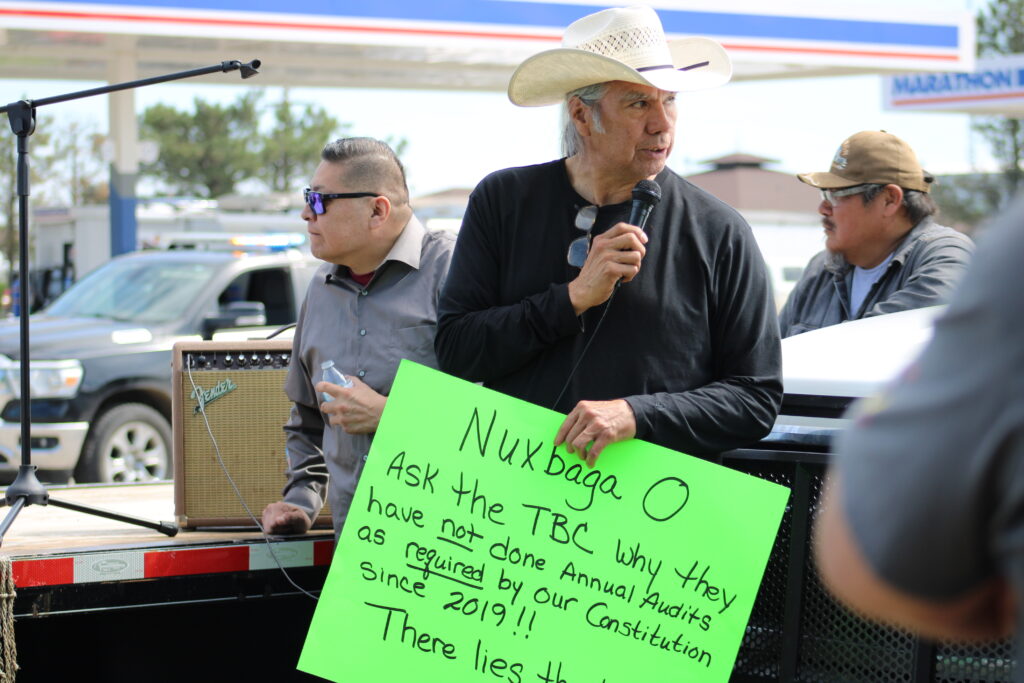

Protesters who object to Mandan, Hidatsa and Arikara Nation Tribal Business Council's lack of accountability to the people, carried a sign noting the Tesoro High Plains Pipeline trespass on individual owners allotted land near Mandaree, N.D. Photo by Jodi Rave Spotted Bear

Protesters who object to Mandan, Hidatsa and Arikara Nation Tribal Business Council's lack of accountability to the people, carried a sign noting the Tesoro High Plains Pipeline trespass on individual owners allotted land near Mandaree, N.D. Photo by Jodi Rave Spotted Bear

After working in the mainstream press as a journalist for 15 years, I was accustomed to calling elected officials – governors, senators, state legislators — and receiving an answer to questions. Those politicians typically responded whether I was asking hard questions or simply needing a reaction to a newsworthy event.

This all changed once I returned home to live on the Fort Berthold Reservation in North Dakota. I could no longer report as a journalist in a manner once considered normal. That’s because the elected leadership of the Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara Nation does not answer to anyone. By all appearances, they don’t answer to each other, either.

In recent years, the lack of accountability within the MHA Tribal Business Council ranks led the FBI to Fort Berthold to investigate tribal corruption. Federal investigators questioned scores of witnesses. Many of those people pleaded guilty. On May 15, ex-MHA councilman, Randall Jude Phelan, was sentenced to prison for bribery and kickbacks.

Despite the corruption investigation, elected MHA Nation representatives of the Three Affiliated Tribes, TAT, still answer to no one. None of this is lost on Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara enrolled citizens. On Saturday, a number of those people joined in a protest march across the Four Bears Bridge to the TAT administrative building in New Town.

People carried protest signs, one of which read: Ask the TBC why they have not done annual audits as required by our constitution since 2019.

If it weren’t for the FBI investigation, Justice Department press releases, and the resulting court records from plea agreements, no one would have known the extent of corruption that was happening within the TAT Tribal Business Council ranks.

The lack of accountability can be linked to the fact that the MHA Nation does not have any open records laws. I am enrolled with the tribe. As a reporter and as a citizen, freedom of information does not exist within our tribal government. In contrast, all state governments, including the federal government, have freedom of information laws or statutes.

State and federal governments also all have a plethora of open meeting requirements. State lawmakers, for example, don’t leave Bismarck or the state of North Dakota to conduct business.

Freedom of information laws allows anyone to submit a written request to a state or federal agency for details on government activities. In the TAT tribal corruption case, it wasn’t tribal leaders or MHA citizens who uncovered the web of bribes and kickbacks. It was federal agents. They intervened because they linked criminal activities to federal funds.

In some civil cases filed against the tribe, tribal leaders successfully avoid legal scrutiny about alleged corrupt activity based solely on sovereign immunity, meaning the government can’t be sued without its consent.

TAT elected leaders have built in extra barriers to accountability. In the legal complaint filed against Phelan of the West Segment: “Each segment receives an annual multi-million dollar allocation of funds from the TAT General Fund.

“Many segments, including the West Segment, deposit this allocation into the segment’s economic development corporation account. Expenditures from a segment’s allocation are not subject to TBC oversight, and the TBC representative has significant discretion as to the spending of the segment’s allocation.”

The West Segment Economic Development Corporation paid contractor Francisco Javier Solis Chacon at least $7.5 million from February 2013 to October 2019. Solis Chacon – an FBI informant who pleaded guilty to criminal acts — provided construction services on the Fort Berthold Reservation. In the July 2020 Phelan complaint, Solis Chacon’s business was paid more than $17.2 million by the MHA Nation and other political segments on the Fort Berthold Reservation.

Phelan, who pleaded guilty to conspiracy, wire fraud, and bribery connected to federal funds, was sentenced to 5 years in prison. He was ordered to pay the MHA Nation $271,900 restitution. The district court “assessed the defendant’s ability to pay” and determined a lump sum payment was due immediately.

We all know tribes have fought hard for decades to exercise tribal sovereignty. Yet, only 5 of 574 federally-recognized tribes have freedom of information laws. This makes it incredibly difficult for reporters to be watchdogs of tribal government. And lack of open records also keeps citizens in the dark.

Tribal leaders of Fort Berthold and across the country must take critical steps to evolve to the next level of self-determination. One possible solution calls for a movement to follow the model of state and federal government freedom of information laws.

Dateline:

NEW TOWN, N.D.