Sovereignty, Community, Press Freedom.

Get the Buffalo's Fire Newsletter.

Get the Buffalo's Fire Newsletter.

The Daily Spark

Quick stories, must reads

- MMIPSioux Falls Police ask the public to help find missing 10-year-old boy

- Arts & CultureBreckenridge History hosts Smithsonian exhibit on Native Americans

- Arts & CultureIndigenous films set for 2026 Sundance Film Festival

- BusinessTribal-owned hotels in St. Paul temporarily close over safety concerns

- Tribal SovereigntyTribal IDs remain accepted at airport security under new TSA program

- Public SafetyPolice urged to address California MMIP crisis through training and coordination

- GamingMaine nears approval of tribal online gaming and casino play

Murdered & Missing Indigenous Peoples

Powwow

Land & Water

Safety & Justice

Northern Plains

Native Issues

Native Nations

Arts, Culture & Sports

Opinion

Stories you might have missed

Traditional foods

Why you should Indigenize your holiday meals — and recipes to help you do it

Treaty Rights

Oceti Sakowin Treaty Council calls for repeal of 1872 Mining Act, protection of He Sápa

Update

Services restored after crypto-mining attempt

Alert Gaps

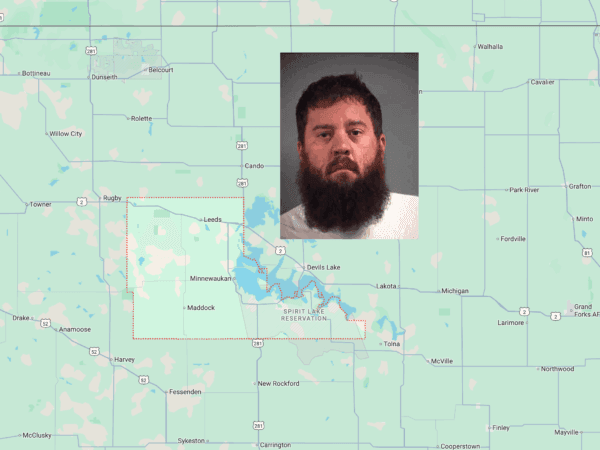

Implementation of North Dakota’s Feather Alert system causes confusion

MMIP

Remains found during search for Isaac Hunt

MMIP Response

North Dakota MMIP Task Force holds first meeting

Community Vision

North Dakota Native-led nonprofit eyes massive cultural center project in Bismarck

Podcast