News Based on facts, either observed and verified directly by the reporter, or reported and verified from knowledgeable sources.

Cleanup of abandoned uranium mines stirs demand for workers

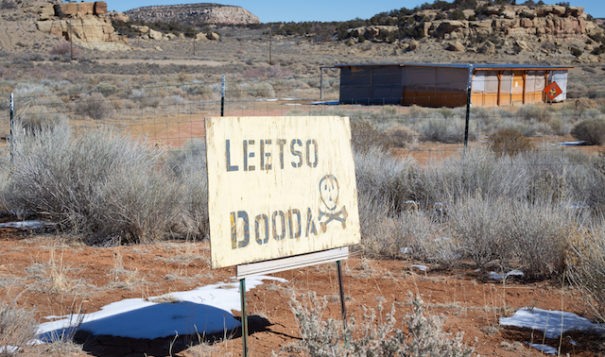

A sign in Diné reads “Leetso Dooda,” meaning “No Uranium,” stands south of the the Quivira (formerly Kerr-McGee) uranium mine in the Red Water Pond Road community and next to their meeting house where the community will hold the 43rd annual commemoration for the mine spill into the Rio Puerco.

A sign in Diné reads “Leetso Dooda,” meaning “No Uranium,” stands south of the the Quivira (formerly Kerr-McGee) uranium mine in the Red Water Pond Road community and next to their meeting house where the community will hold the 43rd annual commemoration for the mine spill into the Rio Puerco.

A growing industry for environmental remediation needs local workers with the right training

This story is part of a collaborative series, “At the Crossroads,” from the Institute for Nonprofit News, Indian Country Today, New Mexico In Depth and eight other news partners, examining the state of the economy in Indian Country. This reporting was made possible with support from the Walton Family Foundation.

Uranium mines are personal for Dariel Yazzie.

Now head of the Navajo Nation’s Superfund program, Yazzie grew up near Monument Valley, Arizona, where the Vanadium Corporation of America started uranium operations in the 1940s.

His childhood home sat a stone’s throw from piles of waste from uranium milling, known as tailings. His grandfather, Luke Yazzie, helped locate the first uranium deposits mined on the Navajo Nation. His father was a uranium miner, then worked for Peabody Coal mine.

Yazzie, Diné, heard the family stories about the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency scanning his family’s home for radiation in 1974, when he was 4 years old, finding several high contamination readings. He was 4 years old.

“Nothing was done,” he said. Not until 32 years later, in 2006, when a new scan was done, leading to eventual demolition in 2009 of the home where he grew up.

His father now suffers from kidney failure and complications with his heart and lungs, ailments that can stem from uranium exposure, research shows. He received financial support through the federal Radiation Exposure Compensation Act, which provides lump sum payments to former uranium workers, but it doesn’t make up for the fact that he struggles with illness.

And it’s not just his dad. Yazzie has survived cancer, and now lives with the prospect that it could come back one day.

“We often hear about environmental justice, social injustice,” Yazzie said. “Flat-out racism is what the local perception is about these long-standing issues, almost 80 years in some areas. Lack of cleanup, lack of funding, lack of emphasis to prioritize cleanup.”

But yesterday’s injustices could mean jobs for the future.

Abandoned uranium mines are found in all corners of the Southwest. In New Mexico, about 1,100 sites where mining, milling or exploratory drilling occurred lie abandoned, mostly in the Grants Mineral Belt, which stretches more than 90 miles from Laguna Pueblo almost to Gallup. Hundreds more dot the greater Navajo Nation, in Arizona, Utah and Colorado.

With big money flowing in the coming decade from settlements with large corporations and the U.S. government for contamination, cleanup of hundreds of abandoned mines will finally begin after decades of neglect.

And that means jobs for tribal citizens and businesses, providing an economic balm for areas that need work. One estimate concludes that about 1,000 jobs could be created over the next 10 years for every $1 billion dollars spent on cleanup, with an average salary of nearly $55,000 per year.

The New Mexico Legislature appears convinced. Lawmakers passed a bill earlier this year to develop a strategic plan for uranium cleanup and to focus economic development on reclamation.

“There are plenty of jobs that can be created cleaning up … abandoned uranium mining sites all across the area,” said Susan Gordon, coordinator of the Multicultural Alliance for a Safe Environment, a coalition of activist groups located in uranium-impacted communities.

But cleanup contracts issued recently by the Environmental Protection Agency have gone to out-of-state companies.

And reclamation brings its own troubles. Some cleanup involves little more than moving contamination from one site to another. The first major cleanup proposed, in Church Rock, New Mexico, exposes the shortcomings of bypassing local communities in the planning process.

Largest radioactive catastrophe in the U.S.

Most of the uranium mining and milling on and around the Navajo Nation occurred before environmental regulations were in place to safeguard human health. When the industry shut down in the 1980s, companies closed shop, leaving hundreds of abandoned uranium mines, extensive surface and groundwater contamination, Radon gas releases and vast amounts of radioactive soil and mining debris.

The U.S. government essentially created the industry in the late 1940s when the newly established Atomic Energy Commission announced it would purchase all uranium mined in the U.S. at a guaranteed price, which it did until 1966. The commission was established after World War II to transfer the nuclear energy assets of the secretive Manhattan Project to civilian control.

By 1967, New Mexico mines were producing half of the total U.S. uranium.

The dangers were significant. On July 16, 1979, the dam of a holding pond at the United Nuclear Corporation uranium mill in Church Rock failed, spilling 94 million gallons of watery, radioactive sludge into the Rio Puerco, running through the local community to Gallup and on to Sanders, Arizona. It is still the largest radioactive catastrophe in the United States.

Larry King, Diné, president of the Navajo Church Rock Chapter, remembers well the day of the spill. King worked at the UNC mine not far from the mill as an underground surveyor, beginning a few months after graduating high school in 1975 until the mine closed in 1983. He heard about the spill from miners coming in for their day shift.

“There was a huge gaping hole,” he said, about the breach at the dam.

The dam failed a few months before the meltdown of the Three Mile Island nuclear reactor near Middleton, Pennsylvania. Three Mile Island led to minimal public health impacts but generated enormous national press coverage and galvanized opposition to the nuclear fuel industry. Much larger and consequential to public health, the Church Rock spill received little attention.

The morning of the spill, the sound of rushing water puzzled people, because it was a clear day.

“I’ve heard from community members who live along the Rio Puerco wash, that’s where the mill waste flowed through, that it sounded like thunder,” King said.

Eventually they learned it was mill waste, he said, but not before people had let their livestock out and they themselves had crisscrossed the wash. Sheep died, crops withered, and at least one woman said it burned her feet. There were similar reports up and down the wash, he said.

The focus on the catastrophe obscured the fact that water had always trickled into the Rio Puerco from the uranium mining upstream, King said.

“Contaminated water did not only flow through the Rio Puerco that one day, on July 16, it was going on for years, 24/7,” he said.

His father’s livestock grazing area ran alongside the Rio Puerco, and his dad extended their fenceline into the wash to make it easier to water the cattle. He played in the water, too.

“There used to be a smell, a real terrible smell, yellow slime along the side… the water always flowed,” he said.

At that young age he thought it was a natural stream. But later, he said, he found out it was contaminated mine water that didn’t stop running until the mining company shut off pumps in the 1990s.

The industry collapsed shortly after the Church Rock spill because of cheaper uranium prices outside the United States. There were 6,800 people employed in 1979. That figure dropped to 2,613 in 1982, before the industry largely shut down completely over the next several years.

Indigenous voices not heard

Perry H. Charley has investigated the scope of uranium contamination for decades.

Recently retired from Diné College where he founded the Diné Environmental Institute Research and Outreach Program, Charley said official counts on Navajo land underestimate the number of abandoned mines — including exploratory mines, drilled shafts and buildings — resulting from the Atomic Energy Commission’s uranium program.

“They left it as it is; they just walked off,” said Charley, Diné, an expert on the health and environmental impacts of uranium contamination. “You have tons of radioactive material scattered all over the Southwest.”

Now, 40 years after the industry shut down, the UNC Church Rock mine that King worked at remains contaminated with debris, but that could change soon.

It’s the only one of 523 abandoned mines on or within a mile of the Navajo Nation nearing the beginning of cleanup, according to the EPA.

But that cleanup plan is controversial. The proposal, developed by the U.S. EPA office in San Francisco, calls for simply moving approximately one million cubic yards of contaminated uranium soil, rocks and other debris across a nearby highway to the reclaimed millsite where the dam breach in 1979 occurred. It’s on private land, but so close it’s still near the local Navajo community. A remaining amount of contaminated mine waste would still need to be cleaned up, through a separate EPA process.

The plan doesn’t reflect the wishes of the Navajo Nation and local residents that the waste be removed entirely. The community will still sit practically next door to the contamination.

“The position has always been off-site disposal. And taking it across the street, literally across the street, does not work for the Navajo people,” said Valinda Shirley, executive director of the Navajo Nation EPA, to state lawmakers at a hearing on uranium last September.

The mill site is regulated by the Nuclear Regulatory Commission, the successor to the Atomic Energy Commission, so the EPA’s plan triggered the need for the agency’s approval. The NRC issued an environmental impact statement for public comment in 2020, and is expected to finalize its decision this summer.

But public education and opportunities for input from the local community about the environmental impact statement were insufficient, Yazzie said.

Direct person-to-person outreach to people living near the site was needed, he said, because many people don’t have phones or reliable internet. Instead the NRC held one in-person meeting in Gallup, and several more online meetings, he said.

“They should have knocked on every door, with the whole plan, bring copies,” he said, “and be fluent in Navajo to go over the entire packet. That never happened. The limited amount of information they shared, over the radio, over internet platforms, they were speaking oftentimes too technical, in English, that some didn’t understand. So, is this an environmental justice issue? Or is this a racism issue?”

The lack of community voices and input is concerning, Yazzie said, because the northeast Church Rock mine cleanup will set the stage for how community members are included in future cleanups.

The Church Rock proposal comes despite the EPA’s 10-year plan requiring that traditional ecological knowledge andDiné Fundamental Law, a set of principles that guide Navajo decision-making, inform its remediation decisions.

The Native view of cleanup is based on ecological restoration, Charley said, but Indigenous perspectives are often missing from non-Native approaches to cleanup, which can lead to reclamation projects failing.

“Modern Western science risk assessment leaves out so much from the Diné viewpoint,” he said. “It leaves out sacredness, livingness, the soul of the earth.”

From the perspective of the Diné people, the traditional belief is that illness and the imperfections of life are an imbalance, and the underlying toxins, such as radioactive waste, are disrespectful to the environment, or Mother Earth, he said.

Holistic healing, he said, is maintained by a “delicate interconnectedness” between the physical, emotional, psychological and spiritual existence of human beings.

To bridge non-Native and traditional approaches to reclamation, it’s important to include traditional Navajos and scientists, like him, who live in impacted communities, Charley said.

Failing to incorporate Native ecological knowledge at the beginning of the process can mean certain communities are overlooked for cleanup because the full impact of toxic exposure they experience is missed. A medicine man, for example, might gather plants for their medicinal properties or for traditional ceremonies from a contaminated area 30 miles away that wasn’t prioritized for cleanup. Taking the plants back home would spread contaminants, a risk that could be missed by non-Native scientists, Charley said.

The result is a high certainty that rural communities that are sparsely populated won’t be prioritized for cleanup when they should be, he said.

New generation of workers

Yazzie said the reclamation field needs a new generation of Indigenous workers to help ensure proper remediation in the decades ahead. It needs people not only trained in reclamation but who understand local perspectives and can communicate effectively with community members.

People like Kirby Morris.

Every week, Morris, Diné, drives 35 miles east from her home in Coyote Canyon to Navajo Technical University in Crownpoint where she studies environmental science and learns to clean up abandoned, hardrock mines.

As a child, Morris would visit her grandmother in Coyote Canyon, on the Navajo Nation in northwest New Mexico, and climb to the top of the mesa behind her grandmother’s house.

“They always said there’s abandoned mines back there,” she said. “You can just see it — a doorway that’s closed up into the hillside.”

After looking at maps of abandoned mines, Morris, now 39, realizes the mine she saw had been used to unearth uranium decades ago.

“We shouldn’t even be near it, but it’s so close, you know,” she said, “just on top of the mesa from the communities down there.”

Morris works on a Navajo Technical University team trying to transform soil from an abandoned coal mine near Socorro so that it can grow plants and vegetation. The idea is to come up with the right “recipe” that can then be used back at the mine to grow ground cover.

Morris and the other Navajo students working on the project could one day employ what they’re learning in uranium remediation jobs.

At the root of her work is a desire to teach her four children about the environment and protecting it for them and Navajo communities.

“I do see it as a career,” she said. “This is something that is, you know, needed here not only on the Navajo Nation but the state of New Mexico as well. It would be a benefit for all of us.”

Dr. Abhishek RoyChowdhury, an assistant professor of environmental science and natural resources at NTU, leads the soil cleanup project for the Socorro coal mine and is working to prepare future environmental scientists from Navajo communities for the reclamation field.

Along with colleagues, he’s building a radiation health physics associate science program that will train students to handle radioactive waste, a specialized process regulated by the government.

“We believe if we can train our local workforce, they will be the main force to solve this issue,” said Roychowdhury, who is non-Native. “If we can provide the education, if we can provide the training, we can build a future workforce who can work for the Navajo Nation, who can work for these external companies who are always looking to hire local people.”

Looking ahead

New attention to environmental cleanup comes after a string of bad economic news for the region, which is made up of a checkerboard of Navajo, federal, state and private lands.

In 2020, big employers near the city of Gallup – a Marathon oil refinery and the Escalante coal-fired power plant in Prewitt – shut down. Three hundred people lost their jobs.

In metropolitan Farmington, another city near the Navajo Nation, the closing earlier this year of the San Juan Generating Station will worsen a steady decline in the labor force. On the horizon looms the expected 2031 closure of another large employer, the Four Corners Power Plant in Fruitland.

Corporate interests and New Mexico elected officials, including Democratic Gov. Michelle Lujan Grisham, hope to tap the region’s vast natural gas reserves to create a new hydrogen fuel industry and replace lost jobs.

Another job-creation idea sailed through the New Mexico Legislature earlier this year: cleanup of abandoned uranium mines. Lawmakers hope mine reclamation can help workers and businesses access jobs if the state helps to coordinate training and fosters relationships.

The idea began to take shape during a 2018 struggle over a uranium mining permit at Mount Taylor, which pitted a need for jobs against desecration of a sacred site of the Navajo Nation and many of the state’s pueblo tribes.

It then bloomed into an influential economic study by the Bureau of Business and Economic Research at the University of New Mexico. In a legislative presentation last year, bureau researcher Rose Rohrer estimated cleanup projects could create 1,000 jobs for every $1 billion spent on cleanup over 10 years, with an average salary of $54,633 per year. Jobs would include general labor, trucking, environmental science, architecture and engineering.

New Mexico lawmakers ran with the idea, passing a law that directs state agencies to develop a strategic plan for mine cleanup, and create or promote programs for worker training and business development. It also created a revolving fund specifically for uranium remediation with hopes for future funding from the state and federal governments and the private sector.

And it created uranium reclamation positions in the state’s Mining and Minerals agency and Environment Department. That gives the agencies additional resources to address legacy uranium mining and mill site contamination through holistic strategic planning, Environment Department spokesman Matthew Maez said.

The effort complements the Environmental Protection Agency’s 10-year plan for uranium remediation on Navajo land, which includes a workforce development component intended to ensure cleanup money flows to Navajo companies and workers.

So far, however, cleanup contracts the EPA has awarded have gone to non-Navajo-owned companies. The EPA doesn’t give preference to Navajo companies in awarding contracts, according to EPA Press Officer Joshua Anderson, but each contract includes an employment plan and training requirements, and companies must file an annual report about how they created “meaningful job opportunities” for Navajo businesses and the Navajo Nation.

In an $85 million contract with Tetra Tech, Inc. in 2017 to assess uranium contamination, the EPA built in criteria to encourage the company to procure services and supplies from Navajo companies, and to partner with NTU to train Navajo students, like Morris, in career paths related to assessment and cleanup. The plan also calls for industry job fairs and advertising to get the word out about contract opportunities.

Cleaning up abandoned mines costs a lot of money. Regulations, laws, and safety issues must be considered when planning for uranium remediation. Millions of tons of radioactive soil will likely be moved to designated repository sites, and workers will need specialized training for handling chemicals or radioactive material and to master guidelines they must follow while on the job.

The economic study singled out time-consuming, costly training as a barrier to small companies breaking into the uranium remediation industry.

Funding for reclamation has been a long time coming, though it got a recent boost through large, corporate settlements and new funding that U.S. Sen. Martin Heinrich, D-New Mexico, attached to last year’s federal infrastructure bill.

But the expected explosion of jobs could be snatched up by out-of-state companies and out-of-state workers without more reclamation money flowing into the state, Rohrer said.

“These are lifetime issues,” Rohrer said, “and they can bring jobs and opportunities for lifetimes.”

This story is part of a collaboration from INN’s Rural News Network in partnership with INN members Indian Country Today, Buffalo’s Fire, InvestigateWest, KOSU, New Mexico In Depth, Underscore and Wisconsin Watch, as well as partners Mvskoke Media, Osage News and Rawhide Press. Series logo by Mvskoke Creative. The project was made possible with support from the Walton Family Foundation.

New Mexico In Depth is a nonprofit news organization that produces investigative, data and solutions-rich stories that can be catalysts for change.