News Article Article pages that do not meet specifications for other Trust Project Type of Work labels and also do not fit within the general news category.

Drawing better lines so that Native votes count

Montana draws electoral districts to reflect politically cohesive minority voting blocs; that could work in other states where Native Americans live.

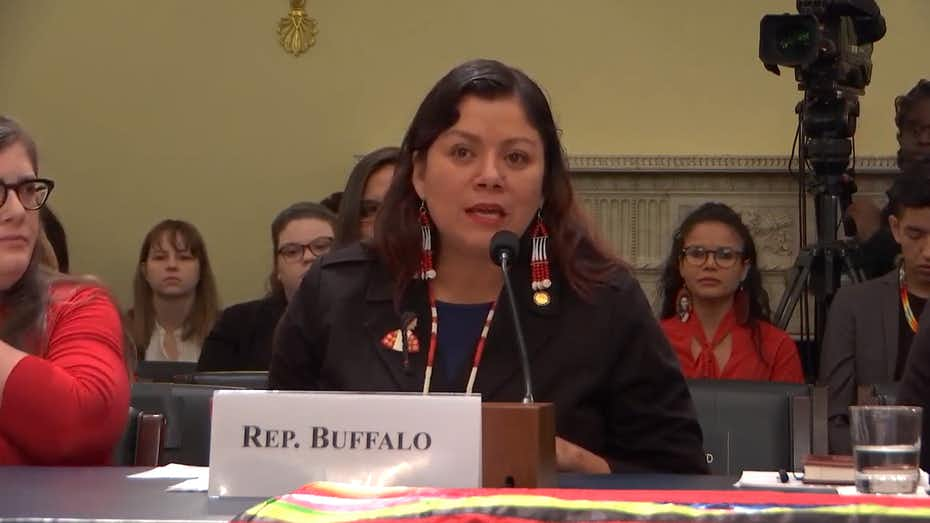

North Dakota State Rep. Ruth Buffalo placed a red ribbon skirt on the table before her, a tangible testament to all missing and murdered Indigenous women. She had arrived in the nation’s Capitol to present testimony before a House Natural Resources subcommittee for Indigenous peoples where she answered questions from Congress members, including Rep. Deb Haaland of New Mexico.

Haaland asked Buffalo to explain the significance of the cloth, her voice a bit shaky and filled with emotion. Buffalo explained the skirt was made in honor of “our sisters,” the ones who never came home. Buffalo had introduced legislation in her home state to help protect Indigenous women from disappearing like fog burned by the sun. Buffalo had organized the search the day pregnant, Savanna Lafontaine-Greywind’s plastic-wrapped body was pulled from North Dakota’s Red River, her baby cut from the womb.

Buffalo and Haaland’s marked a rare moment in politics where Indigenous women lawmakers could work together to improve a historic plight upon their communities. Their wins during the 2018 midterm elections were a long time coming. It took more than a century for Buffalo to become the first female Native Democrat elected to the North Dakota Legislature. It took more than two centuries for Haaland to become the first American Indian woman elected to Congress — a title shared with Sharice Davids of Kansas.

After her testimony, Buffalo, a citizen of the Mandan, Hidatsa and Arikara Nation, returned to North Dakota where she represents Fargo’s District 27, which is 370 miles from her traditional homelands on the Fort Berthold Reservation. The reservation is encompassed by District 4. Only one Indigenous person has ever been elected from District 4 because the white population overwhelms the Native vote. Tribal citizens make up only 31.8 percent of the district’s population. Research shows that in racially polarized whites overwhelmingly vote for white candidates and Natives vote for Native candidates.

Tribal citizens in Montana have proved in court that the state’s districting process diluted their vote.

Montana and North Dakota illustrate the vast difference between how Natives are included or kept out of the political process. Congress enacted the Voting Rights Act of 1965 to address discriminatory voting practices against people of color. Tribal citizens in Montana have put the law to work to create legislative districts where they can elect candidates of choice, whereas Natives in North Dakota remain embattled for representation in the state legislature:

- Since 1989, North Dakota has had six American Indian individuals elected to the legislature compared to Montana where a total of 68 seats have been filled by American Indians, some who were re-elected, during the same time period.

- In 2019, North Dakota had one Native woman in the legislature, compared to six Native women in Montana.

- American Indians comprise 1.4 percent of the North Dakota Legislature and represent 5.5 percent of the state population. In comparison, Natives make up 8 percent of the Montana Legislature and represent 6.7 percent of the state population.

- Only one reservation in North Dakota has a majority American Indian district compared to Montana where all seven reservations can choose to elect a Native candidate of their choice. Studies show that in racially polarized voting areas, whites vote for white candidates and Indians vote for Indian candidates.

American Indians in Montana didn’t wake up one day to parity in the state legislature. It was a hard-won, decades-long battle against a discriminatory electoral process. Along the way, they championed redistricting, engaged in grassroots organizing and finally proved in court that Montana had diluted the Native vote, a Section 2 violation of the Voting Rights Act.

“I would say the name of this game is vigilance,” said Janine Pease, a citizen of the Crow Tribe, who became a lead plaintiff in the Windy Boy v. Big Horn County lawsuit. “Whoever you have working on elections has to work hard every time.”

Redistricting

Pease, an educator and the founding president of the Little Big Horn College, and other members of the Crow and Northern Cheyenne Reservations in Montana, took Big Horn County officials to court in 1993 for denying them the chance to elect candidates of their choice for school boards and the county commission.

This Windy Boy v. Big Horn County suit marked the beginning of redistricting efforts in Montana, starting at the school board level, then county and eventually leading to redrawing electoral boundaries. Today, Montana boasts one of the highest rates of American Indian representation in a state legislature. In 2018, 12 Native legislators represented seven reservations with Native majority districts as well as three cities in Montana.

Noted civil rights attorney Laughlin McDonald of the ACLU and Billings, Montana attorney Jeffrey Renz worked with Pease and others to bring the ACLU’s Voting Rights Project first case in Indian Country to court. The project since has filed hundreds of voting rights cases and considers the Windy Boy suit one of its most notable wins.

The case was filed in 1983 after citizens on the Crow and Northern Cheyenne Reservations grew tired over repeated, experienced discrimination, from school and county officials, a claim they proved in court. They wanted a better way of life for themselves and for their children. In 1980, only 5 percent of Big Horn County employees were Native even though Natives made up 41 percent of the voting age population.

If they could elected to school boards and county commissions, they might improve standards of education, get better healthcare and enjoy the fruits of employment by participating in the political process. If they wanted to get elected, they had to show the county was diluting their vote.

Three factors define vote dilution under Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act: political cohesiveness of the minority group, geographically compact and the existence of a significant white voting bloc. Montana Natives from all the reservations have long sought parity in politics.

“I want to recognize and acknowledge the shoulders on which we stand that started this work long ago, decades ago,” said Marci MacLean-Pollock executive director of Western Native Voice, a nonprofit, nonpartisan social justice organization based in Billings, Mont. Her staff and volunteers focus their efforts on year-round community organizing to build positive social change.

“Nobody has done this in Indian Country the way Western Native Voices is statewide, reservation and urban,” said MacLean-Pollock. “There’s just no blueprint for us to follow. So we’re creating the blueprint and working with organizations, such as Western Organization Resources Council, who’ve been around for 40-plus years and taking from them their experiences and using them in ours.”

“A big, big part of the success is collaboration with Native organizations, non-native organizations,” she said. “I really, truly believe collaboration is critical to the success of making change in our communities.”

During the 2018 midterm elections, Western Native Voice hired community organizers to knock on 33,769 doors, send 11,064 text messages and give voters 482 rides to the polls. Eighty percent of the people they contacted voted in the midterm election.

MacLean-Pollock said her organization helps people understand how the political process affects them. This includes getting people to learn and observe the state legislature. Community organizing is a building block for understanding redistricting because engaged voters elect people who represent their interests, she said.

Montana Natives showed up to vote in record numbers during the 2018 midterm election with more than 7,000 new people casting a vote, a 60.3 percent increase from 2014. The Fort Belknap Reservation had the highest increase percentage, owing to a strong coalition of grassroots voting rights organizations. “They just all really work together in making sure that they are rocking the vote.”

Western Native Voice annually trains some 10 to 20 community organizers and has expanded operations with Western Native Voice North Dakota and the North Dakota Native Vote. “We’re in the process of getting an advisory committee together which will then form our board of directors,” said MacLean-Pollock.

Nicole Donaghy worked as a field organizer for North Dakota Native Vote campaign during the midterm election to address North Dakota’s controversial voter I.D. Law, which required voters to have street addresses instead of post office boxes. A law that disproportionately affected Native voters. Tribes and several other voting rights advocacy groups, such as the Lakota People’s Law Project and Four Directions, also helped secure record turnout in North Dakota in response to the I.D. Law.

Minority Majority representation

The Windy Boy case ended decades of discriminatory districting in Big Horn County. No longer would white majority voters in diminish the Native vote. The Windy Boy case, as well as statistical analysis from other Montana cases, proved white voters overwhelmingly vote for whites while American Indians tend to vote for American Indians. In 1986, the court ordered Big Horn County to adopt a new system for elections.

Pease suggests community members participate in public input districting meetings leading up to the release of 2020 Census figures. In 1999, the Montana Supreme Court appointed Pease to lead the Montana Redistricting and Apportionment Commission. It is the duty of districting commissions to uphold Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act so racial and language minority voters have an equal opportunity to participate in the political process and to be reflected in the elected legislative body.

In 2003, tribes across Montana saw greater gains in majority Indian senate and house districts with a new state districting plan. All the reservations across Montana have Native majority districts and can elect candidates of their choice.

Sen. Jason Small represents District 21, which encompasses both the Northern Cheyenne and Crow Reservations. He’s said it’s pretty much “a given” that Native voters will elect a Native legislator in his district. On the other hand, it’s also competitive. Small ran on the Republican ticket and won his district in a bid against another tribal citizen who had previously served the area as a state representative.

“If you have reservations, I don’t know why you wouldn’t set up for the reservations to have their own sort of representation,” said Small. “In all honesty I mean it makes sense because people aren’t the same. People’s conditions are not the same. The concerns of people are not the same. And at the end of the day everybody has to get together and make everything mesh and work out. But if I don’t have a representative that is somewhat duplicative of my own situation, what good are they going to do me because they’re not going to understand or know what’s happening in my mind little piece of the world.”

Small enjoys the camaraderie with his fellow Native legislators. “It is a reasonably tight knit group, everybody pretty much knows what everybody’s doing,” he said. “Everybody can keep an eye out on stuff and try to keep everything going in the right direction. There’s 12 Indian legislators now, that’s a heck of a group. That’s a force.”

Buffalo, on the other hand, said she wishes there were more Native legislators, or tribe-related lobbyists in North Dakota, but that hasn’t stopped her from being her own force. Five of six pieces of legislation she introduced have cleared the House. At least one — a bill that would allow Native students to wear plumes and eagle feathers at graduations — was awaiting the governor’s signature. She’s also galvanized a new cadre of Native voters who have joined ranks with her during the current legislative session.

She represents one of the largest cities in North Dakota, a coup achieved by knocking on 6,500 doors, making some 3,000 phone calls and sending more than 10,000 mailings to local voters. But, true to her roots, Buffalo values her rural upbringing and cultural ways.

On Dec. 31, Buffalo’s family invited friends and relatives to celebrate in a traditional honoring for the newly elected legislator. Buffalo, who dons a smile like a morning sunrise, greeted guests who arrived for the gathering at the Four Bears Casino banquet room. She wore a tan cotton sweater and royal blue skirt adorned with colorful rows of ribbons. In the give-away tradition, a meal is provided to guests and the person being honored gives away gifts, such as Pendleton blankets and star quilts.

Many people answered the call to an open microphone and spoke words of praise on behalf of Buffalo. Similar words were shared by her senior legislator, Rep. Haaland of New Mexico who told Buffalo during the Indigenous Peoples subcommittee hearing: “You were meant to serve. And I’m inspired by the vast amount of work you’ve already done.”

Podcast: Jodi Rave ‘This Land is Our Land,’ conversation with Janine Pease.