News Based on facts, either observed and verified directly by the reporter, or reported and verified from knowledgeable sources.

Civil rights investigation finds Rapid City Area Schools ‘discriminated’ against Native students

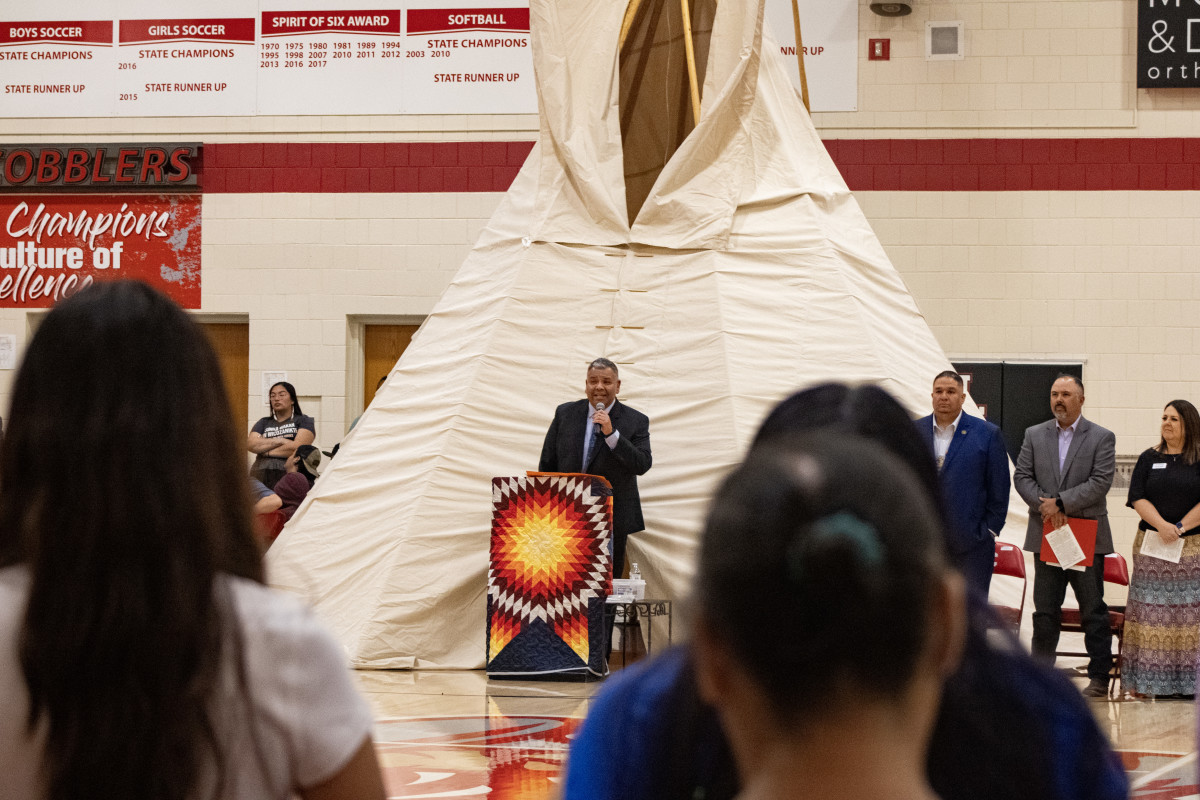

A federal investigation found that Rapid City Area Schools ‘discriminated” against Native students. (Photo by Amelia Schafer, ICT/Rapid City Journal)

A federal investigation found that Rapid City Area Schools ‘discriminated” against Native students. (Photo by Amelia Schafer, ICT/Rapid City Journal)

School district signs agreement to close the gap with Native students with more staff and advisory committee

A federal civil rights investigation of Rapid City Area Schools found significant differences in the way Native and non-Native students are treated, citing discrepancies in the way they are disciplined and in their access to advanced placement courses.

The report, by the U.S. Department of Education’s Office of Civil Rights, was released on May 29 outlining the findings of an investigation launched in response to a 2010 complaint from parents and community members about the handling of Native students.

“OCR’s review found evidence indicating that (1) Native American students were being disciplined more frequently and more harshly than similarly situated white students, and (2) that Native American students were discriminated against with respect to access, referral, identification, and selection for the district’s advanced learning programs and courses including honors courses and Advanced Placement courses,” according to a statement released by the Office of Civil Rights.

The district has entered into a voluntary agreement to resolve issues brought up by the investigation. The agreement, signed by district Superintendent Nicole Swigart, does not provide any admission of noncompliance with federal civil rights laws but spells out steps the district must take.

“That report provides a sobering perspective of the way things have been in Rapid City Area Schools for a number of years,” said Ira Taken Alive, a citizen of the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe and the Title VI director for Rapid City schools. “But the report gives us an opportunity to all come together with students in mind, student success and student proficiency in mind, to come up with some solutions.”

The district has agreed to examine the root causes of racial disparities in the district’s discipline and advanced learning programs and implement corresponding corrective action plans, including hiring several staff members to oversee corrective actions.

The district also agreed to form a stakeholder equity committee, but the agreement does not specific if any or how many Native people would be included.

“We’re looking forward to continuing earnest work on our resolution agreement terms,” Taken Alive said.

Investigation findings

The report used data from the 2014-2015 and 2021-2022 school years to examine discipline rates, truancy referrals, arrests and access to Advanced Placement courses. The civil rights office held listening sessions with the community in 2022 and interviewed district administrators in 2023.

The report found that, from 2014-2015, Native students were referred for truancy 4.9 times more frequently than White students and 5.49 times more than White students from 2021-2022.

And in some schools in the Rapid City Area School District, Native American students were eight times more likely to be disciplined than their White peers, according to the report.

In the two sample school years, Native students were also less likely to be placed in Advanced Placement courses than White students, with fewer than 3 percent of Native students enrolled in AP courses, the investigation found.

The report detailed that the district lacks culturally relevant curricula and support services that respect and incorporate Indigenous knowledge and traditions, and a stark achievement gap between Native and non-Native students.

Indigenous students in Rapid City face high rates of poverty, homelessness and a lack of belonging that limits their access to education, according to data from the district’s Indigenous Education Task Force.

When asked about low attendance rates and high tardy reports among Native students, Swigart responded that Native families operate on “Indian time,” making students often two hours tardy.

“The Superintendent reported that certain Native American tribes, such as the Lakota, Dakota, and Nakota Tribes, do not commonly value education and inform their students that they do not need to graduate,” the report states.

The comment drew sharp rebukes from Native leaders.

“That is such a harmful characterization of a non-homogenous group of people,” said Amy Sazue, Sicangu and Oglala Lakota and a former educator and current executive director of Remembering the Children, an organization aimed at honoring survivors and victims of the Rapid City Indian Boarding School.

“In her naming the Lakota, Nakota, Dakota people, there are around 70 tribes represented in our school district, but apparently you only have those students who aren’t achieving, only the Lakota, Dakota, Nakota,” she said.

The comment drew sharp rebukes from Native leaders.

“That is such a harmful characterization of a non-homogenous group of people,” said Amy Sazue, Sicangu and Oglala Lakota and a former educator and current executive director of Remembering the Children, an organization aimed at honoring survivors and victims of the Rapid City Indian Boarding School.

“In her naming the Lakota, Nakota, Dakota people, there are around 70 tribes represented in our school district, but apparently you only have those students who aren’t achieving, only the Lakota, Dakota, Nakota,” she said.

In an email to the Rapid City Journal and ICT, Swigart said the statements attributed to her were misleading and inaccurate.

“As a member of our community for more than 50 years and as someone who has devoted more than 33 years of my life to serving our school district, I have always been committed to treating everyone with the highest level of respect,” Swigart said. “ I adamantly disagree with those comments attributed to me in the Office of Civil Rights report. The transcript of my interview is both misleading and inaccurate as to comments I allegedly made regarding my views of the Native community. I do not hold those beliefs to be true and I have never uttered such hurtful words. Our Native American Tribes solidly value … education and graduation and well [sic] partner with our district for which I am so grateful, proud and celebrate,” Swigart said in an email.

In an email to the Rapid City Journal and ICT, Swigart said the statements attributed to her were misleading and inaccurate.

“As a member of our community for more than 50 years and as someone who has devoted more than 33 years of my life to serving our school district, I have always been committed to treating everyone with the highest level of respect,” Swigart said. “ I adamantly disagree with those comments attributed to me in the Office of Civil Rights report. The transcript of my interview is both misleading and inaccurate as to comments I allegedly made regarding my views of the Native community. I do not hold those beliefs to be true and I have never uttered such hurtful words. Our Native American Tribes solidly value … education and graduation and well [sic] partner with our district for which I am so grateful, proud and celebrate,” Swigart said in an email.

The Rapid City Journal and ICT requested a copy of the transcript of the conversation, but the Office of Civil Rights had not provided a copy of the transcript as of Monday, June 24.

“This is the leader of your school district making very ignorant, racist comments and she’s trying to say she doesn’t remember saying that,” said Mary Bowman, Hunkpapa/Oglala Lakota and the executive director of the Oceti Sakowin Community Academy. “But this is a legal document where your testimony was recorded, but to me that’s very troubling. That’s the leader of your district making those kind of comments. Where is that resolve to try and fix some of those things, if that’s the belief you have? There’s no intention to make things better.”

In an email to the Rapid City Journal and ICT, Swigart said the statements attributed to her were misleading and inaccurate.

“As a member of our community for more than 50 years and as someone who has devoted more than 33 years of my life to serving our school district, I have always been committed to treating everyone with the highest level of respect,” Swigart said. “ I adamantly disagree with those comments attributed to me in the Office of Civil Rights report. The transcript of my interview is both misleading and inaccurate as to comments I allegedly made regarding my views of the Native community. I do not hold those beliefs to be true and I have never uttered such hurtful words. Our Native American Tribes solidly value … education and graduation and well [sic] partner with our district for which I am so grateful, proud and celebrate,” Swigart said in an email.

The Rapid City Journal and ICT requested a copy of the transcript of the conversation, but the Office of Civil Rights had not provided a copy of the transcript as of Monday, June 24.

“This is the leader of your school district making very ignorant, racist comments and she’s trying to say she doesn’t remember saying that,” said Mary Bowman, Hunkpapa/Oglala Lakota and the executive director of the Oceti Sakowin Community Academy. “But this is a legal document where your testimony was recorded, but to me that’s very troubling. That’s the leader of your district making those kind of comments. Where is that resolve to try and fix some of those things, if that’s the belief you have? There’s no intention to make things better.”

Swigart declined an interview with ICT and the Journal, noting that she needed to “consult with a personal attorney to see if this is an appropriate time for an interview.”

‘Unique challenges’

Fourteen years ago, a group of parents and community members filed a report with the U.S. Department of Education’s Office of Civil Rights. The group argued that Native students were over-disciplined and lacked the same access to advanced courses that White students had.

Nationwide, Indigenous students experience high dropout rates. In 2022, Native American and Pacific Islander students experienced the highest high school dropout rates at 9.9 percent and 9.1 percent respectively. However, that number did decrease for Native student’s previous highs, 12.8 percent in 2012 and a record high of 13.2 percent in 2015, according to the National Center for Education Statistics.

For the 2023-2024 school year 3,716 students self-identified as Native American. Of those, about 2,423 students completed the federal 506 form for American Indian Education, Taken Alive said.

Between these numbers, anywhere from 19 percent to 30 percent of the Rapid City Area Schools student body is Native American, according to the city’s Title VI Office of Indian Education.

Students were most often disciplined for cell phone usage, insubordination and truancy, according to data from the Indigenous Education Task Force.

Students often lack access to safe housing and many need to work to support their families.

In 2021, 517 students in the Rapid City School district were identified in the Mckinney Vento, or homeless, count. Of those 517 students, 372 or 72 percent of those students were Native American – meaning that around 15 percent of all Indigenous students in the Rapid City Area School district were homeless, according to data from the school district’s Indigenous Task Force.

“We do have high rates of poverty and high rates of unemployment in the Native community, not just in Rapid City but across the state,” said Taken Alive, the Title VI Director for Rapid City schools. “Those factors present some unique challenges to our families and our communities where there’s a large presence of Native American students.”

Bowman said the low attendance, high dropout rates and low graduation rates for Native students boil down to the different barriers the students experience to learning. The barriers create a feeling that they don’t belong.

“A lot of times our people are portrayed negatively,” Bowman said. “When kids are in public school settings they don’t see themselves in the workers there, in the teachers and staff. We have a district with about 20 percent Native students; it’s important for them to see Indigenous people in that setting as teachers and staff.”

The district launched in 2021 an Indigenous Education Task Force aimed at providing recommendations for improvements in the educational experience, learning environment and outcomes for Native students.

In 2022, the task force issued reports with recommendations to the district based on feedback from community members, tribal members and families. These recommendations included increasing access to social work and mental health resources, increasing enforcement of district bullying policies to protect students and including more Indigenous culture in classrooms.

In 2023, when the Office of Civil Rights conducted interviews around Rapid City, several principals told officials they’d never heard of the report.

Further recommendations

Another major issue addressed in the report was the presence of School Resource Officers or School Liaison Officers, generally referred to as SROs, in schools.

The district, as well as many South Dakota school districts, include SROs for a majority of law enforcement activities at schools during school hours, but aren’t meant to be general school disciplinarians. However, in 2023 interviews with the Office Of Civil Rights, administrators stated that SROs are responsible for a majority of the arrests and citations made against students at schools.

For many students, discipline referrals are their first introduction to the court system, a situation that has been dubbed the “School to Prison Pipeline.” On average, Native students in South Dakota are 7.9 times more likely to be arrested than White students. In the Rapid City Area School District, Native students received 5.5 times more law enforcement referrals and were arrested 5.84 times more than White students in 2021-2022.

The rates were significantly higher at three schools. At General Beadle Elementary School, Native students were referred 10.7 times more; at South Middle School, 14.7 times more; and at East Middle School, 9.7 times more than White students. Native youths and people in general are overrepresented in the justice system.

East Middle School was responsible for a bulk of the disparities, according to a resolution letter submitted to the district with the investigative findings. The school, which has a Native population of 12 percent, gave 50 percent of all in-school suspensions and truancy referrals to Native students in 2021-22.

“I’ve seen it, when working at North (Middle School) I’ve seen kids enter the court system,” Bowman said. “They (SROs) get depended on too often to discipline students.”

SROs have also been criticized for unnecessary use of force when breaking up student fights.

Using SROs may also damage relationships with the community, the Office of Civil Rights letter stated that often when schools send SROs to student homes, families will not open the door, fearing interactions with law enforcement.

At its core, one of the reasons students may not want to come to school is that they struggle to feel welcomed – an issue that could date back to the boarding school era, Bowman said.

“I feel that a lot of the social ills that we see today came from that intergenerational trauma,” Bowman said. “The trauma of people trying to make you forget who you are and where you come from. That’s a basic question, a basic need to know the answers to those questions.”

For many Native people, boarding schools were their first introduction to Western education.

“When we think about education being the ultimate weapon of assimilation for our people, it’s still succeeding in what it was intended to do,” said Sarah White, Oglala Lakota and the founder and executive director of The South Dakota Education Equity Coalition. “It’s still seeking to assimilate and contribute to cultural genocide. As both a student who lived that experience in colonized classrooms and as an advocate, especially an urban Indigenous advocate, I realize the lack of access and the perpetuation of colonization that’s happening within systems.”

The South Dakota Education Equity Coalition is a community of stakeholders established in 2022 to advocate for equitable outcomes for Indigenous students. The coalition provides training initiatives for parents and community members on youth engagement strategies.

“When we think about it historically, the active disengagement and disenfranchisement of our communities by school systems was designed to keep us out,” White said. “Fast forward to today, we see standards and metrics that still reflect a standard that isn’t necessarily shared by Indigenous communities. So it’s no wonder why we’re not achieving at that rate because our values are not often reflected in these spaces.”

White has 8 years of experience working and advocating for Title VI Indian Education Programs. She previously worked at Rapid City Area Schools’ Title VI Office and at Omaha Public Schools in Omaha. Working in Title VI, White said often Indigenous people are left with the burden of needing to solve systemic issues affecting Indigenous people.

“There needs to be meaningful and active relationship building between the school district and Indigenous communities,” White said. “We need to remedy the harm and the stigma around what schools have stood for within our communities and celebrate the richness that Indigenous genius has to offer the entire school district because right now the only time we’re talking about Indigenous students in Rapid City is in a deficit and that’s really harmful.”

This story is co-published by the Rapid City Journal and ICT, a news partnership that covers Indigenous communities in the South Dakota area.

Our stories are worth telling. Our stories are worth sharing. Our stories are worth your support. Contribute $5 or $10 today to help ICT carry out its critical mission. Sign up for ICT’s free newsletter.

Dateline:

RAPID CITY, S.D.