The billboard project is expanding to Oregon

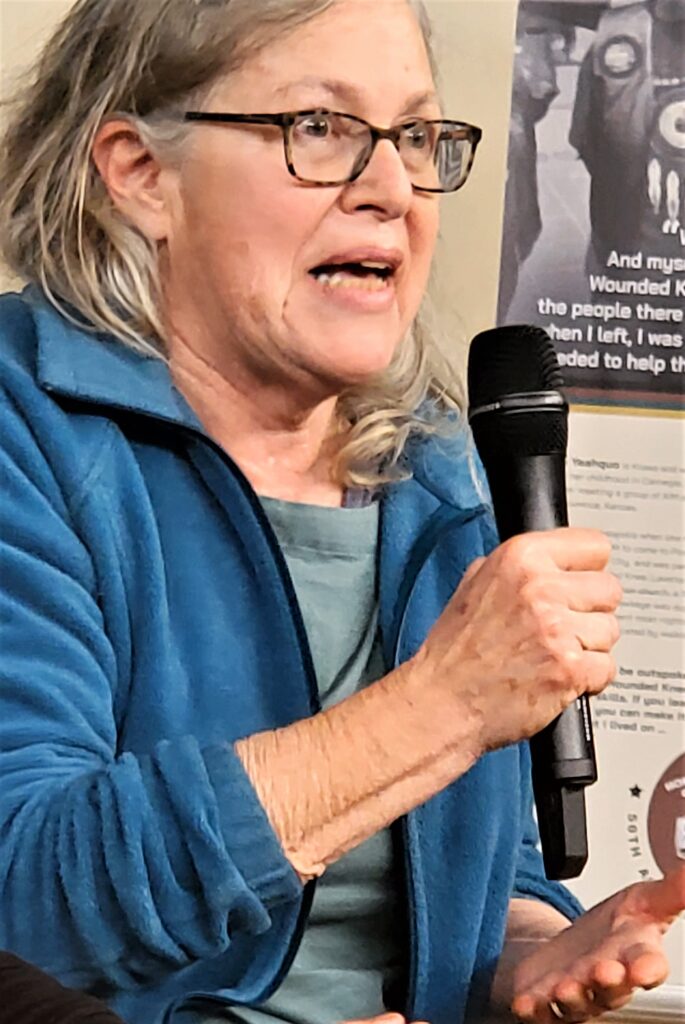

Marcella Gilbert, Warrior Women Project leader, is master of ceremonies 50 years after 1973 Wounded Knee occupation.

“I woke up that morning to gunshots. And we were in a firefight,” Lavetta Yeahquo recounted. The Kiowa Native of Oklahoma had her 19th birthday while under siege by federal troops at the 1973 Wounded Knee Occupation here on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation.

With “nature calling,” Yeahquo said she braved the shelling in a dash to an unfinished outhouse. It was no more than a hole in the ground, “so I went, and I jumped in that hole. I did my thing, and I said I gotta make sure I get back safe. I stuck my head up. They must have seen the top of my head, my hair. I felt the wind from the bullets. They were shooting at us, and I got back down.”

“I woke up that morning to gunshots. And we were in a firefight.”

Lavetta Yeahquo, Kiowa Native of Oklahoma

Yeahquo told the story during a Feb. 25 round table discussion, “Honoring the Wounded Knee Matriarchs,” at Porcupine, 8 miles north of Wounded Knee. The event was part of a four-day commemoration during the 50th anniversary of the American Indian Movement takeover at the 1890 massacre site.

It was not glamorous. Yeahquo was stuck in a bunker between the lines of fire during the 71-day clash, she said. In fact, it was the very spot in which Frank Clearwater took a fatal bullet to become one of two Native casualties during the standoff. The other was Buddy Lamont.

“We were close to death,” she said. “A lot of us felt that, but that was my first experience. That’s something I’ll never forget.” Yeahquo said she experienced post-traumatic stress disorder and, for a long time, never told anyone about it.

The Native non-profit Warrior Women Project invited her to the table to testify on this occasion as part of a 25-year ongoing effort to establish a living oral history archive. “We wanted to take time to recognize the matriarchs of Wounded Knee,” said Cheyenne River Sioux tribal citizen Marcella Gilbert, a project leader.

At the round table was lawyer Fran Olson, a member of the Legal Defense/Offense Committee, or WKLD/OC, convened by the National Lawyers Guild to assist Wounded Knee insiders. “One of the things that impressed me the most throughout the entire period was that the local leaders of the movement were largely women, and the national leaders of AIM were largely men,” Olson said. The AIM members, “to their deep credit, refused to allow the government to separate out the women to keep them, the local people, in the background,” she said. The organization’s involvement “had all begun as a local movement, and the women leaders were very important.”

The Oglala Sioux Civil Rights Organization, OSCRO, on Pine Ridge called for AIM backup, according to testimony collected by the Warrior Women Project. The civil rights group had come to consider the Oglala Sioux tribal administration of Richard “Dickie” Wilson a reign of terror.

Wilson’s so-called “goon squad” made it so “two people couldn’t even talk on the street. They throw you in jail,” said one witness to the abuse of law and order. They would “push the women aside and laugh at us” during protests at tribal offices, calling for his impeachment. Dissidents lost their tribal and BIA jobs. Federal marshals “on top of the FBI building” menaced opponents of the administration, she said.

AIM had a base in Rapid City. When OSCRO called there for help, the women decided they should go to a gathering at a meeting hall on the reservation. “I noticed there was a lot of what looked like military vehicles,” said Madonna Thunder Hawk, a veteran of AIM since the Alcatraz Island takeover in 1970.

“And then I looked on top of the FBI building, and there were sandbags, and you could see barrels of big guns. I don’t know what they thought we were doing. We were coming through town, you know? It wasn’t planned. I mean, I had my 10-year-old son with me.”

Thunder Hawk was the inspiration for the award-winning independent documentary feature film “Warrior Women.” When Elizabeth Castle, who has a doctorate degree in Native history, interviewed the Cheyenne River Sioux tribal citizen, the achievements brought to light became the movie. In turn, the movie launched the Warrior Women Project, producer and co-director Castle said in Porcupine.

Thunder Hawk, Gilbert’s mother, was a medic in the “liberation” of Wounded Knee. Pinned down by federal firepower at a remote trading post near the gravesite of 19th Century massacre victims, they declared the Independent Oglala Nation. Some 200 people refusing to surrender to charges for the takeover demanded U.S. recognition of the 1868 Fort Laramie Treaty. They called for the removal of the Oglala Sioux Tribal Council and new elections.

“And then I looked on top of the FBI building, and there were sandbags, and you could see barrels of big guns. I don’t know what they thought we were doing. We were coming through town, you know? It wasn’t planned. I mean, I had my 10-year-old son with me.”

Madonna Thunder Hawk, AIM veteran

Vigilante roadblocks of food deliveries and federal refusal to permit medical assistance characterized more than two wintery months of battle and negotiations. A stand down of arms and evacuation ended the occupation on May 8. The odyssey is documented in the book “Voices from Wounded Knee 1973.” Akwesasne Notes, a newspaper based at the Mohawk Nation in New York State, originally published it without the author’s names.

The anonymity was to protect book contributors from subpoenas in the hundreds of resulting legal cases, author Diana Brown told Buffalo’s Fire. WKLD/OC reproduced the book for the anniversary, and Brown spoke to the round table about the occupation.

Gail Sullivan, one of several members of the WKLD/OC attending the Porcupine gathering, told Buffalo’s Fire the positive impact of 1973 events is palpable today. Visiting from Boston, she said she can feel that racial tension has subsided substantially here in the area.

At the 40th anniversary celebration of KILI radio station on Feb. 24, AIM Wounded Knee leader Bill Means announced an investment in the “Voice of the Lakota Nation.” As chairman of the FM channel’s board of directors, he said he has a two-year goal of raising $2.5 million for the community broadcaster. Speakers at the occasion in Rapid City, S.D., agreed a mainstream media blackout at Wounded Knee ‘73 was motivation for creating the first independent Native station. Powwows in Rapid City and on Pine Ridge on Feb. 26 celebrated the half-century of struggle for treaty rights sparked by Wounded Knee ‘73. An annual walk from four directions to the mass gravesite of the Wounded Knee 1890 massacre attracted people from across Turtle Island and as far away as Ireland.

Talli Nauman

Contributing Editor

Location: Spearfish, South Dakota

Spoken Languages: English, Spanish

Topic Expertise: Climate, Environmental and Social Justice; Right to know; Spearfish, South Dakota

See the journalist page© Buffalo's Fire. All rights reserved.

This article is not included in our Story Share & Care selection.The content may only be reproduced with permission from the Indigenous Media Freedom Alliance. Please see our content sharing guidelines.

Identification not yet made

UTTC International Powwow attendees share their rules for a fun and considerate event

Radio collaboration highlights importance of cooperation in a season of funding cuts for local media

A memorial in the Snow County Prison, now the United Tribes Technical College campus

Standing Rock Sioux Tribal Chairwoman Janet Alkire tells crowd, ‘We’re going to rely on each other’